WHEN I WAS A KID, MY NICKNAME WAS BUCKWHEAT. Buckwheat was the lone black kid in the Our Gang series of shorts, better known as The Lil Rascals. He was dressed as a Topsy-esque image of the African-American pickaninny stereotype, with bowed pigtails, a large hand-me-down sweater and oversized boots. He spoke ineloquently and was often the butt of jokes, little more than comedy relief for the other Rascals.

Needless to say, being called Buckwheat as a kid was not a term of endearment.

Being one of the only black kids in school growing up, I had darker skin than my classmates, bigger lips, and a big nappy ‘fro thanks to a father who never grew out of the 70s. What that meant for him was a son who looked like a mirror image of him; what that meant for me was a childhood of teasing and taunting. Not just because of my hair, but the way I spoke, the clothes I wore, my obsessive love of Transformers, and the color of my skin. I was classified as “other” from an early age, having attended a majority white private school, where in a beach town like Santa Barbara, shades of skin darker than pearl were usually a tan, and any absence meant the African-American population dropped by about 50%.

Buckwheat wasn’t the only nickname I was given growing up. Zimbabwe. Oreo. Fat Lip. The names given by kids of privilege that have likely long forgotten their taunts by now, but still remain with me decades later. I hear the echoes of their taunts. I see the laughs on their faces. I feel the tears that rolled down my eyes when I shared with mom and dad how kids made me feel.

But they do not compare to what my parents experienced.

My mom, a now-retired scientist, always shared her stories of growing up on the south side of Chicago. She started working at 14 because her father had died; she lost her older brother to police violence during the civil rights movement of the 1960s; her mom and another brother each suffered from mental illness during a time when anyone who was seen as abnormal was cast aside by society.

She was also a Star Trek fan. This was endearing to my dad, an air force pilot and sci-fi geek partial to the writings of Issac Asimov. He too grew up in poverty, a few hours from Chicago in East St. Louis. Most of his family never came out of the poor conditions of the area. My grandmother, his mom, died at 108 in the same 800 square foot house she raised him and his eight siblings in. He was the youngest, born in the mid-1940s, coming into his prime during an age where he was able to enlist in service of a country he wasn’t eligible to vote in, trying to find identity in a land he had no voice in.

When my parents moved to California to start careers, they did not do so to run away or start fresh, but to provide an opportunity for their kids to have the ability to be raised in better conditions than they had. My sister was born in the 70s, myself in the 80s, a lengthy time away from the overt discrimination of my parents’ time. We were fortunate to have a relatively middle class experience, but they kept close the pain of their experiences growing up, and made sure I understood the journey they went on.

Throughout their lives, my parents were survivors. My dad of a war many will never understand. My mom of a cancer that has claimed far too many. Both lost siblings and parents due to injustice in this country’s more tumultuous days. Both judged for their skin in ways the micro-aggressions and disrespect of today cannot compare. They experienced losses I could never fathom, but still led my sister and I through inspiration, through support, through listening.

They led with love.

When I wanted to cut my hair so I wouldn’t be called Buckwheat anymore, they said OK, but ensured I knew a haircut didn’t change who I was. This helped me to be a little less fearful of my image as I grew up.

When I wanted to speak better so I wasn’t teased for my verbal ticks and struggles articulating what I wanted to say, they got me a vocal coach, but reassured me that nothing was wrong with me, regardless of what kids teased. This helped me score college-level language (and reading… and math…) skills on a Stanford assessment when I was just in the 3rd grade.

When I wanted to keep all my Transformers as I grew older so I could transform my imagination (cheesy? Yes, and I don’t care; it worked), they did not let me forget where they came from, and did not let me change who I was to make other people happy.

Lesson Number One: It was much harder than it seemed.

AS I KEPT GROWING, I KEPT FALLING. Or rather, there was no one outside my family who was willing to pick me up. Many were content with watching me fall, get up, fall again, get up again, satisfied only when my face was horizontal, because they were pushing me down rather than holding me up. There were numerous distractors, people who said they were my friends or teachers or figures of authority who had zero trust that a black kid would be anything more than what society deemed as inevitable for him.

Thinking back to Buckwheat, the first words he ever spoke on film were “here I is.” It wasn’t so much an introduction as it was a response to a command by his slave master, who demanded to know where his runaway slave had gone to. Buckwheat wasn’t trusted; neither was I.

In high school, I was in honors classes, a member of the California Scholarship Federation, a library assistant, the editor-in-chief of the school paper, winner of the poetry contest three out of four years, and proudly part of the video productions club. The principal, who once confiscated my Motorola pager that my mom gave me so I could be updated on her status in the hospital, enrolled me for an introductory meeting with Job Corps, assuming that despite my grades and academic achievements and extra-curricular activities, I needed vocational training because I would not get into college.

Why?

“You won’t ever be good enough” was a common phrase I heard from many people, regardless of socioeconomic status, relationship, gender, or otherwise. I was not good enough to be a public speaker. Not good enough to obtain a master’s degree. Not good enough to write. Not good enough to obtain a promotion, or a raise, or get a good LSAT score, or get into a doctorate program, or work in a certain industry or for a certain company. And when I achieved those goals, I was Arrogant. Boastful. Angry. Unappreciative. Ungrateful. So the echos of doubt raged against the pulse of my heart, hoping for peace and happiness when all I could find was a broken mirror sneering at everything I wanted to be happy about.

This reached a tipping point when I worked directly for the head of a global consulting firm. He considered himself one of the smartest people in the world. He regularly introduced himself as one of the leaders of the business world. Anyone who didn’t go to an Ivy League school (specifically Harvard, Yale, and Columbia; even Stanford was beneath his notice) was neither smart nor talented. People who made less than $200,000/year were lazy. People in his employ did not need career development; being lucky enough to work in his presence was good enough for him. Leaders were winners, and winners were those who were privileged to have the best education, the best income, and work for the most valued companies.

As such, he said I needed to show greater appreciation to him. I wasn’t that smart, but someone like me was given an incredible once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be something I wasn’t destined to be. He paraded me around in front of his Fortune 500 and AM Law 100 CEO, CLO, and Manager Partner friends, saying how well-spoken I was, how articulate I can be, and that if it wasn’t for him, I would be just another statistic. I would be just like Buckwheat.

Here I is.

Sure, the pay was good; the travel and the opportunities to meet people of influence and power were even better.

The dehumanization was not worth any of it.

Working directly for him made me question my humanity, my worth, and my credibility as a professional. When I quit, he said it would be the biggest mistake of my career, and I should think carefully if I want to ever have a respected career. I would fail because I am not good enough to work for anyone other than him.

He was not the only nightmare made reality. One, the head of a global financial services firm, said success is defined by DNA. Another, a leader on the people team of another tech company, said she wanted to fire half the company because they’re not smart enough to be in the same room as her. Each showed their worth based on the privilege or right to be in a position of power and influence, because it was expected of them, because they were above others, because they were winners–and everyone else, a loser.

Lesson Number Two: It was easy to believe them. It was even easier to not believe in myself.

I WANTED TO FIGHT GRAVITY. I carried the weight of judgment on me for years, never understanding why those who were able to be positioned into authority felt justified in holding back or holding down those who had not yet, or not wanted to, achieve the titles or connections or incomes they had achieved.

But if the workplace of winners wasn’t for me, maybe the halls of academia were.

I became interested in leadership, as a theory, as a methodology, as a history. I obtained advanced degrees in leadership partially because I wanted to know if I had been cursed by assholes all of my life, or if there was an underlining meaning that I had yet to articulate.

Throughout history, the understanding of leadership had trended to be about winning. Leaders were those with followers. Followers who listened to or appealed to the commands of those who were above them. Obedience. Fealty. A need for direction and purpose by the person on top.

Early studies focused on traits, with the assumption that people in leadership positions would display more leadership traits than those in subordinate positions. Contemporary research at the time furthered that example by identifying how leaders tended to be higher in traits such as extraversion, self-confidence, and, amazingly enough, even height. Tony Robbins identified the top leadership trait as confidence. “Confident leaders win over and inspire others because everyone else wants to embody confidence too.” Ralph Stogdill identified qualities that included age, physique, appearance, intelligence, knowledge, responsibility, and self-confidence.

Leaders were indeed winners; born, privileged, and appealed to, while followers were losers; unappealing, unable, unfit.

Leaders said “tell me where you are”; followers said “here I is.”

You won’t be good enough because you weren’t supposed to ever be good enough.

There were obvious problems with the trait approach to leadership. Since advocates of this theory suggested that certain traits were linked to strong leadership, why doesn’t every person who exhibits these supposed “leadership traits” become a great leader? What about great leaders who don’t possess the traits typically linked to leadership? What about the role of situational variables or characteristics of the group?

The questions lingered, and my studies grew. I learned about servant leadership. I leaned into situational leadership. I blossomed at the mere mention of transformational leadership, looking for and taking advantage of any opportunity to link my lifelong love of Transformers with methodologies around the way we work. And as I dived deeper into my education in leadership, and had the opportunity over the years to lead a variety of teams at companies as unique as Twitter and Irvine Company, I began to understand the missing link.

Many of these poor leaders did not experience loss. They did not understand what it was like to be challenged in life, either personally or professionally. They had no accountability for their own failings. They approached how they dealt with people as a zero sum game. There was no room for improvement, because they had already reached the highest mountain, and those they looked down upon did not deserve to climb it with them.

And if they had experienced loss, it was something they refused to accept. They buried it deep, and with it, they buried their humility.

Lesson Number Three: My story is not unique.

I HAVE NOT ALWAYS BEEN TRANSPARENT. Despite my love for people, I was influenced by the bad leaders or poor examples in my life to not be my authentic self. My father was raised in a harsh period of this country, lost his father at a young age, and had strict Air Force training that inspired his parenting. When I woke up crying at 8 years old because of something mean my classmates had said to me, he shook me, told me to stop crying, because no one would ever care for me, no one really loves me, and the only one I could count on was myself. He clearly said this out of frustration, likely because I had woken him and my mother up in the middle of the night, but it was something that affected me, and is an image I can still see clearly to this day.

So I didn’t let people get to know the real me. I never let anyone in to know who I was. My failures were not lessons to be learned. My doubts were not meant to be shared. When I led people, be a leader in name, but not in action; pretend your word is without fail, even if it gnaws at you, because it is better to be seen as strong than show a hint of weakness. This was incredibly foolish, of course, and created even more stress for me, until I decided to be fully authentic and open about who I was, what I hoped for, and how much I cared for everyone that was on my team.

It was a long road to get there. It took losing friends and failing relationships. It took countless hours of coaching. It took a medical diagnosis. But today, when I look at the medications that sustain me, the friends no longer here, and the opportunities missed, I allow myself to smile–because I know who I am, and I know what I’ve both lost and gained to get here.

So rather than using the poor examples of leadership to guide me, I lean deeper into the best leaders in my life. Those I’ve worked with or those I was inspired by. And I try to embrace loss as much as they experienced it.

The leaders of the civil rights movement knew loss when many in this country fought against them. Society saw them as less; they fought to be recognized as more than. Legislation wanted to turn back the clock; the blood and tears and words of many proved that there was no direction but forward. They advocated for something bigger than themselves, hoping to raise the stakes of equality and equity for all, even if they did not live to see it fulfilled.

Those fighting for the freedom to marry knew for decades they had an uphill battle for those with deeply conservative beliefs in positions of power. They made failing part of their strategy, knowing that before they could rise to have the same rights as straight couples, they had to lose some battles and learn from them.

People like Muhammad Ali, and Malala Yousafzai, and Hadiza Bala Usman, were mindfully authentic in their approach to the world. They knew that they could not win the hearts and minds of others if they were pretending to be something they were not. They reminded us that, in a world with over seven billion people, we are all unique, so let’s lean into who we are and use our life experiences to empower others.

The sacrifices they endured allowed them to be free.

My mom embraced loss when she was diagnosed with cancer. Moving forward was not negotiable. Looking back was not an option. Here we are today; let’s figure out how we will use the life and days we have together to make a difference tomorrow.

Even Billie Thomas, the first actor to portray Buckwheat, found his path. He enlisted in the U.S. Army, decorated with a National Defense Service Medal and a Good Conduct Medal. He did not let the role of Buckwheat define him, even if the world looked to him as the kid who first proclaimed “here I is!” or garbled phrases like “otay!”

He used the presumptions of others to build something greater for himself.

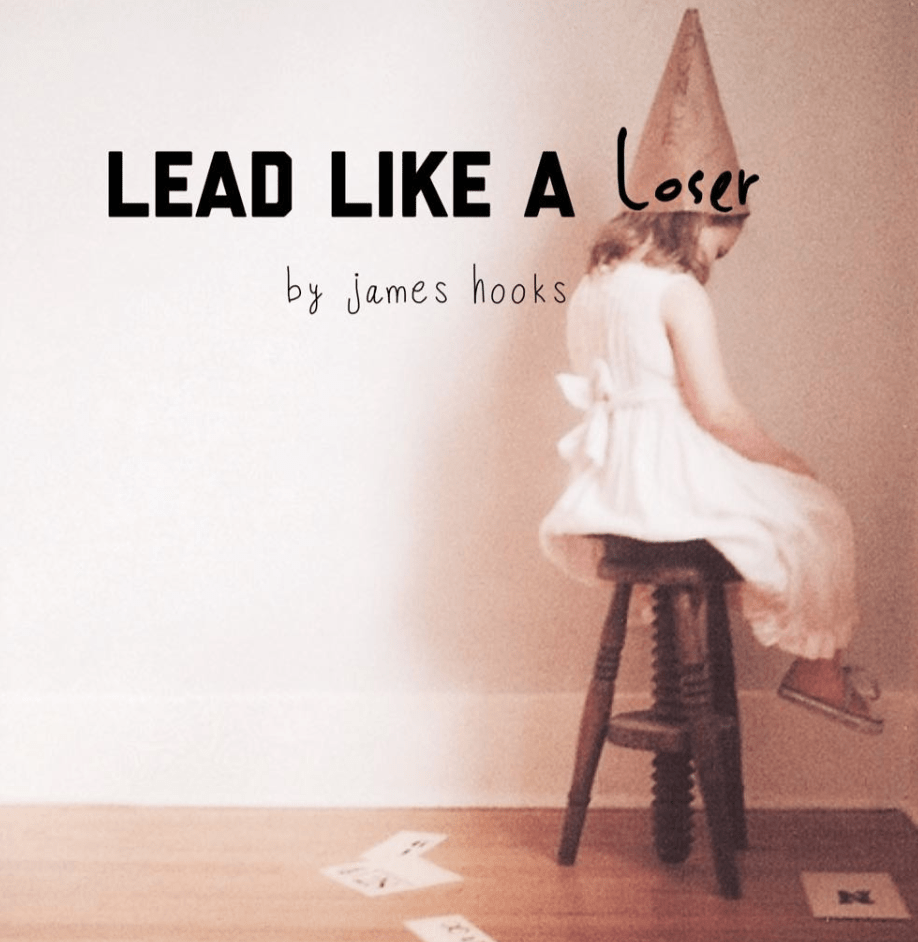

RATHER THAN CHASING LEADERSHIP, I REDEFINED IT. I think relentlessly on the life lessons learned through hardship, the sacrifices those I admire made, and the hopes and dreams of everyone I encounter, and build a community where we are all able to experience a shared leadership that embodies growth. I lead like a loser by remembering what it felt like in my lowest moments, and work to lift others up in theirs. I lead like a loser by knowing I am not always right, that I am not special, but I can help others find, navigate, articulate, and develop a career and life experience of their own. I lead like a loser because I do not want to win at the expense of others.

But what does it mean to lead like a loser?

It is not about needing to feel down on yourself, or self-depreciating, or having a woe is me attitude. It is knowing that nothing is perfect, and no one is perfect. It is about collaborating and not just assuming good intent, but providing feedback that can move good intent to great impact. It is identifying the humanity within us all; it is tugging the boat behind you in troubled waters until the boat can float and eventually propel on its own; it is building and coaching others so that they can eventually surpass your level of experience and influence, so that they can lead others to do the same.

Leading like a loser is advocating for people and values. A positive, value-driven culture has consistent guiding values, a shared purpose, teamwork, innovation, appreciation, encouragement, and recognition. These are not just buzz words to score on PSCs or metrics by which a Pulse survey are measured and acted on. Leaders engage employees in identifying and developing their own personal value and mission statements, which can then lead to development and alignment with organizational values. But these values mean nothing if leaders do not fight for them.

The people and their values become a guiding force for an exemplary culture as leaders ensure all employees are working to support the values. Transformational leaders create cultures where personal development is encouraged, effort is valued and rewarded, and people are respected as equals.

Leading like a loser is making failing, and hope, a strategy. Failure is not a horrible, heart-wrenching event. It only has power because we have been conditioned to be afraid of it. We make attempts; the desired result is not always going to happen. You will experience failure again, and again, and again. Welcome to being human.

When was the last time you experienced loss? When was the last time you were on the losing end of a project you were responsible for? When was the last time things simply failed, and you were fully accountable for it? Embrace it all. Identify the opportunities. And build on that. It is okay for you to fail. It is okay to allow others to fail. It is okay to develop a culture of not winning. The best leaders are the ones who experience, and understand, loss. They do not think being on top of an hierarchal environment is the embodiment of success. They don’t even have to be considered people managers. They just have to have the understanding that with failure, comes growth, and with growth, comes improvement. We are all in this together.

Which is where hope comes in. Some say hope is not a strategy, but it can be. In many environments, it must be. If we share the same values for a better tomorrow; if we want to build a global community focused on closer connections and greater kinship; if we want to leave tomorrow better than how we found yesterday; hope is at the center of it all. And it can be at the center of how we build our teams, our company, our world.

Leading like a loser is having mindful transparency and authenticity. Authentic leadership does not come from the outside in; it comes from the inside out. Many who have experienced loss know what it means to feel from their hearts. There are those who say never to show your soul, never reveal your feelings, never let people know who you really are. Ignore them.

Leaders who lead from the heart, with transparency and authenticity, are more successful in building relationships and identifying strengths. Transparent leaders share their visions and goals through constant communication with their teams. A transparent leader wears their vision, and their heart, on their sleeve, acting as a role model by persistently living out their dreams and sharing their goals with others. People are more functional when they have a clear sense of their goals and expectations of their leaders, and when leaders listen.

Leaders let people know they care. Leaders let people know they’re important. Leaders let people know that what they say, and who they are, matters.

Leading like a loser is understanding that leadership is not a bonus. I was once told that being a leader is merely something that is a nice-to-have, but is not necessary nor considered for the work that we do. The intent was good, yet I vehemently disagree and reject the premise.

Leadership is not something extra that should not be weighed less than the rest of our work. It is, however, a choice we make. And when you see leadership potential in others, you foster it; you develop it; you reach out to help them become a leader because, like you, they’ve worked hard to collaborate with others and bring out the best in their capabilities.

It is not a bonus to pull all the ships behind you until they can sail on their own; it is transformative.

Leading like a loser also means nothing is set in stone. The leadership situations I expressed are based on my experience, my current situation, and the environment in which we work and live. For just like being a leader requires transparency and authenticity, it also means being able to adapt, to change, to transform, and to admit that you will not always be right. Every day we are given a unique opportunity to be advocates of transformation. Our lot in life does not define nor constrain our potential for good. It can inform our direction, but sometimes, we plan to turn left, but new information and new experiences will force us to turn right.

Lesson Number Four: Life is a journey. There is no Google Maps for where we are going. But if we can articulate who were are, we can better navigate that journey.

I HAVE LEARNED MANY THINGS IN LIFE. Some of those lessons came through loss. I learned that change is hard, often harder than we care to admit. I learned that it is easy to believe detractors and not search for the core of our truth. I learned that, though my circumstances feel unique, they are not. As such, I am not special by any means, nor have I ever claimed to be. What I am is someone who wants to leave the world a better place than how I found it. I am someone who wants to be a catalyst for those looking to ignite the drive within themselves. I am someone who believes in the greater good of our humanity.

We are here to be our best selves. To create community. To build. To make an impact. We are the engines of Earth. We create ripples that spread across our shared experiences. Whether we make giant leaps of innovation that can improve the way we all live, or small gestures of gratitude that may brighten just one person’s day, each of us holds the ability and responsibility to reflect the very best that humanity has to offer. We may not feel the changes firsthand, we may sweat and cry and bleed only to see ourselves staring back in frustration, but it is better to build a fortress in the desert than die silently in a crowd.

Perceived fragility may find strangers witnessing unexpected strength. Greatness lies within all who are willing to reach out for it. Add value to your life by giving life to your values. Have conversations that can shape minds and create ideas. And take actions that will make our home a better place today than it was yesterday.

Let’s not close the door on the losses we have experienced. Open that door and embrace the beauty and ugliness of life.

Open your hands and the universe will reach back.

Open your minds and explore your undiscovered journey.

Open your voices and sing “here I is.”