Maybe it’s the reboot of Full House. But everywhere I look, there are kid books and television shows that present conflict only to tidily resolve it within 32 pages or 22 minutes. They end in words like “happy,” or “fun,” or wordless images like peaceful slumber, a subliminal message that, if my kid is representative, never works.

Those rare books that aren’t completely happy don’t sit well with all parents. YiLing Chen-Josephson’s recent article on the subject includes her censorship of Maurice Sendak’s Pierre, in which she changes the titular character’s refrain of “I don’t care!” to “I care!” in hopes of averting apathy in her young reader. The change ruins both the meter of the book (as well as Carol King’s delightful version) and its suitable moral. Pierre’s blasé attitude toward his breakfast, his parents, and his own life is what drives the plot; without it, there is no room for his future growth. Chen-Josephson recognizes that her censorship makes no narrative sense, and that she is butchering one of our country’s most-beloved children’s authors, but, as a parent, she just can’t bear reading “I don’t care.”

But as with all literature, the best children’s books are those in which there are real people acknowledging real emotions. Like so many kids who became adults my age, I loved Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. From the moment he wakes up to the moment he goes to bed, Alexander is in a rotten mood. There’s no falsely happy ending, aside from his mother’s calm acknowledgement of Alexander’s feelings: “some days are like that.” (As a kid you probably didn’t notice what a bad day Alexander’s mom is having. With every turn of the page, she’s a mirror for some of your own worst days.)

Now that I’ve become a parent, I’ve added Pierre, and Alexander, and a host of other not-so-happy books to my child’s shelves. But our stand-out favorites are all from Lemony Snicket. Although perhaps best known for A Series of Unfortunate Events, Snicket has also authored a wonderful collection of picture books that explore a wide and complex range of human emotions. Snicket tackles heavy themes (fear, depression, death), while remaining simultaneously light-hearted and playful.

It’s okay to be scared. That’s the main message of The Dark. In its soliloquy toward the close of the book, the dark nicely captures how darkness can be both scary and reassuring: the same dark closet that scares you at night is also the place to keep your shoes.

Each of Snicket’s picture books features a different illustrator, whose work contributes to its emotional weight. The Dark is masterfully illustrated by Jon Klassen. As Lazlo makes his way to the dark’s home (the basement), the light gets dimmer and dimmer until finally, the pages are pitch black, but for the spaces illuminated by Lazlo’s flashlight.

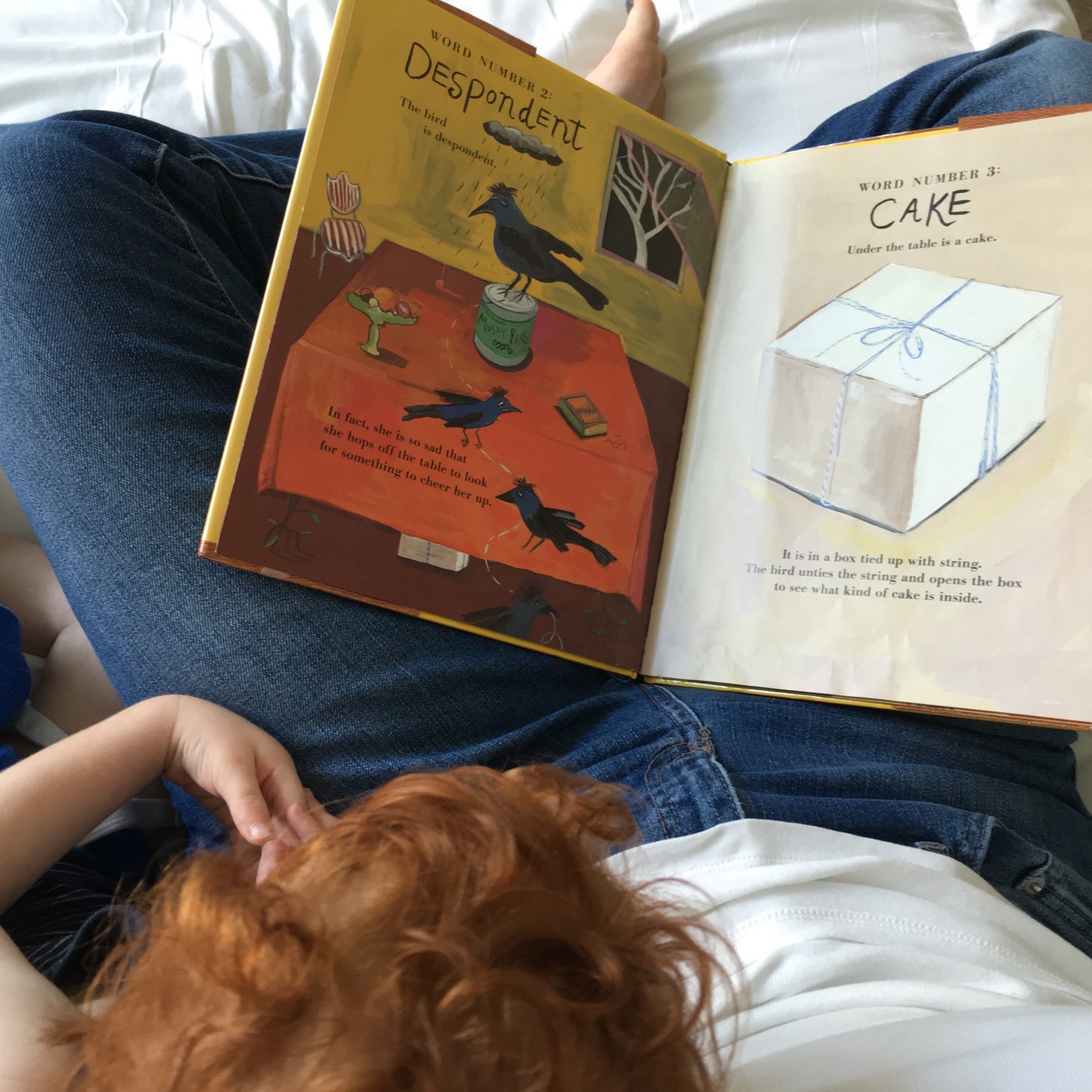

Snicket’s primer 13 Words opens commonly enough, with a picture of a bird. Word number 2, however, is “despondent.” The book features a dog attempting to cheer his sad avarian companion to no avail: neither cake (word number 3), nor a hat with panache (word number 12), nor a mezzo-soprano (word number 13) will cheer it. 13 Words is one of those rare picture books that deepens on every reading, whether it’s noticing that the bird is reading Kafka, or realizing the seaside highway and camera-wearing characters off to the sides of the page suggest that the bird is unhappy in a destination others go to to be happy, or thinking that you’d probably be depressed if engaged in a pursuit as empty as the bird’s. The book ends with a song, but “the bird, to tell you the truth, is still a little despondent.”

The Composer is Dead is a dark Peter and the Wolf. The book opens on a dead composer: “He was not humming. He was not moving, or even breathing. This is called decomposing.” An inspector arrives on the scene to interrogate the orchestra. He interviews each section in turn, so that the reader’s understanding of classical music thickens along with the plot.

The narrator is delightfully snarky as he lampoons the Poirot-type investigator and insults the suspects, all while defining musical concepts in precise but playful terms: “The violin section is divided into the First Violins, who have the trickier parts to play, and the Second Violins, who are more fun at parties.” The full half hour CD accompaniment can be played with or without narration. Both are beautiful, but would be slightly improved by a sound for page turns. When listening to it, it’s hard to remember that you’re reading a children’s book, and that’s the point: Snicket does not dilute his themes or his vocabulary for even the youngest readers, challenging them to take on themes that adults sometimes forget they’re capable of handling.

Originally published at www.snackdinner.com.

Originally published at medium.com