Written by Hitendra Wadhwa, Professor of Practice at Columbia Business School and Founder of The Institute for Personal Leadership. The article was originally published on February 13, 2015.

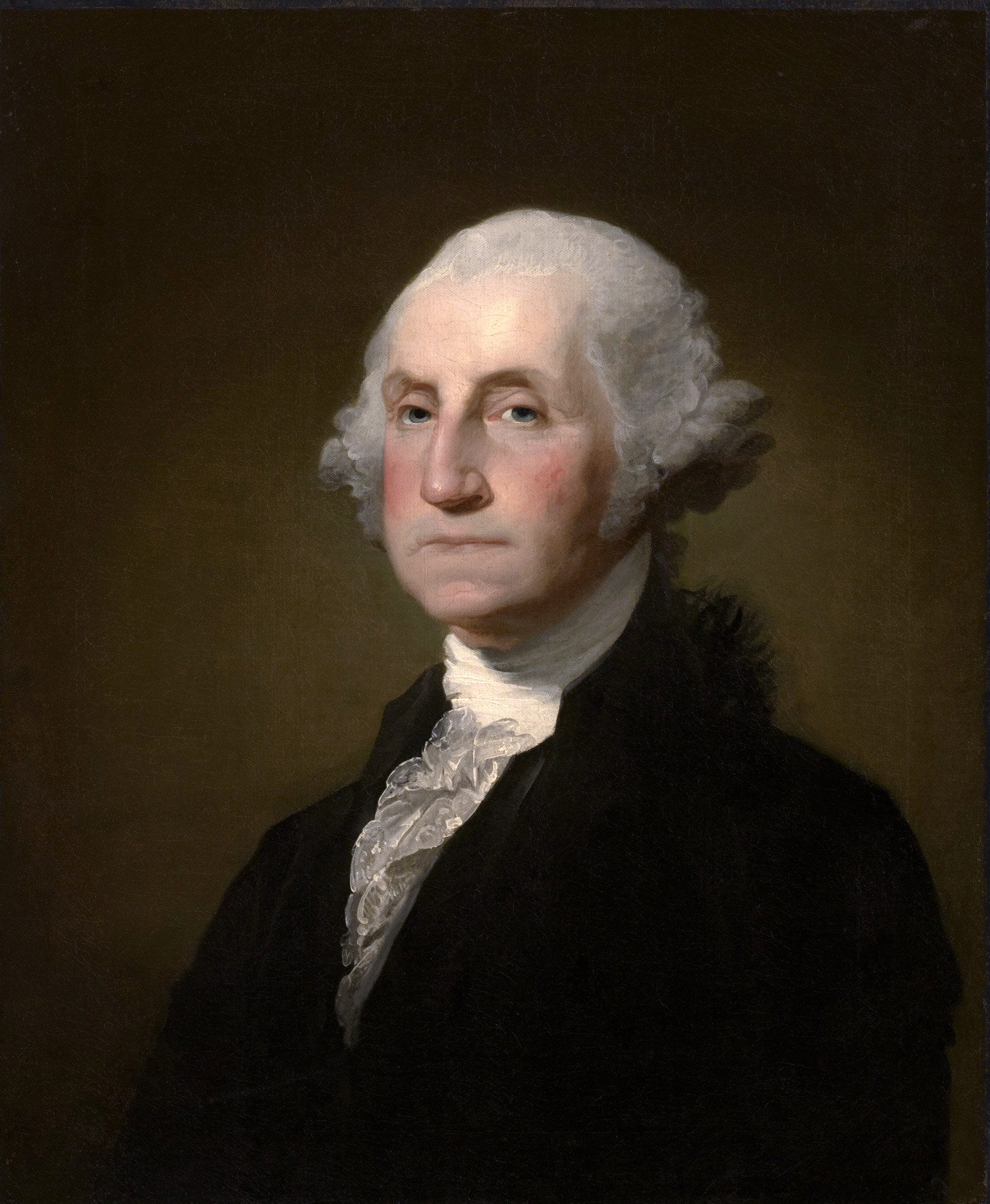

We have been taught that all great leaders – like George Washington, whose birth we commemorate on President’s Day – have been paragons of ambition. It is the fuel that propels them forward in life and leadership. It is the clay that they mold into purpose and action. We too should seek ambition and practice it. So why would I invite you to cultivate surrender, a quality that is the opposite of ambition? Because when we study a great life like George Washington’s, we find that while ambition brought them to the door of success, it was surrender that provided the key for them to unlock that door.

Washington displayed strong ambition from a young age. Though his origins were humble and he never received a college education, Washington distinguished himself in combat as a young officer in the Virginia militia, served the British with distinction in the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War, married a wealthy widow who catapulted him into Virginia’s social elite, and acquired thousands of acres of land along the western frontier. But a series of disappointing experiences left him in contempt of his British military superiors and unhappy with the way remote rulers from England held sway over the economic destiny of their colonial subjects in America.

So, over time, his personal ambition was transmuted into a much bolder and broader vision. He wanted people to wage a revolutionary war to shake off the shackles of British rule across the 13 American Colonies. He wanted these colonies to come together to form a perfect union, a nation governed by a strong federal government. And he wanted this fledgling nation to serve as a beacon for the world. As he once put it, “It should be the highest ambition of every American to extend his views beyond himself, and to bear in mind that his conduct will not only affect himself, his country, and his immediate posterity; but that its influence may be coextensive with the world, and stamp political happiness or misery on ages yet unborn.”

The Evolution of Leadership

Executives who participate in my leadership development programs observe that the life journey of great leaders like Washington often commences with a personal quest for discovery and achievement. Gradually their vision expands to include the world around them, and each passing experience sharpens this vision until their ultimate purpose emerges in sharp relief.

Once he was appointed the commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington went on the offensive, seeking to finish the war quickly and victoriously. But his troops–a motley crew of volunteers, largely untrained and frequently underfed–proved no match for the British forces. Thousands of his soldiers were killed, and thousands more were taken prisoner by the British. John Adams commented after one disastrous defeat, “In general, our Generals were outgeneralled.”

After numerous setbacks and a modicum of victories, Washington was offered sage counsel by some of his generals. The British army was not going to be vanquished anytime soon, they said, and the Continental Army was in no position to engage in direct combat. He would need to place a higher emphasis on preserving his troops by actively avoiding engagement with the enemy except under suitable conditions.

This view flew in the face of his fearless military spirit, but as the losses mounted, he started to see the wisdom in taking a more patient and adaptive approach to the war. He began exercising more restraint in engaging in direct conflict with the British army, stating, “I wish that it was in our power to give that Army some capital wound … but in consulting our wishes rather than our reason, we may be hurried by an impatience to attempt something splendid into inextricable difficulties.”

What he had expected to be a brief war ended up lasting seven years. Over time, Washington and his men, with support from France, succeeded in demoralizing the enemy and inflicting major losses. The death knell for the British was struck when their commander Lord Cornwallis made a tactical blunder in Yorktown, Virginia, forcing the British to surrender to Washington. By restraining his urge for immediate results, surrendering his attachment that the war take a certain course or end by a certain date, and keeping the fighting spirit alive in his army, Washington was finally able to emancipate the Colonies from British rule.

The Principle of Surrender

As the British Army withdrew from America, Washington turned his attention to the next stage of his vision, on how the Colonies would be governed. Other revolutionary leaders, before and since, have typically anointed themselves as head of state, and there was a broad clamor among his wide base of supporters for Washington to crown himself king. But to Washington, this would have violated the very principle on which the American Revolution was founded–to give the American people the right to shape their own destiny. He dearly wished for the Colonies to unite in forming a strong federal government that would pay off America’s debts and preserve justice and liberty across the land. But by now he had learned that he should not seek to simply push his agenda through by sheer will. The right conditions had to emerge for the American people to support his vision.

So once again he put into practice the principle of surrender–of non-attachment to outcomes–that he had mastered during the war. He strode into Congress, resigned his commission to “retire from the great theater of action,” and rode off into the sunset as a private citizen. A few days earlier, commenting on the prospect of Washington surrendering his power to Congress, Britain’s King George III had said, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

He now operated from the sidelines as he patiently waited for the right conditions to emerge for nation building. Even during the war, he had struggled to convince the Colonies to support Congress and the war effort. His troops at times went without food, pay, and shoes as they struggled to get financial support from the Colonies once the initial patriotic fervor gave way to a loss of hope and idealism.

After the surrender of British troops in 1783, the Colonies, basking in their newfound freedom, were averse to the idea of losing their autonomy to a federal government that would enforce laws and collect taxes nationwide. Washington observed that “all things will come out right at last, but like a young heir, come a little prematurely to a large inheritance, we shall … run riot until we have brought our reputation to the brink of ruin…. The people must feel before they will see.”

Eventually, events such as a farmers’ rebellion in Massachusetts stoked fears of anarchy, of a nation that was ungovernable, and the Colonies were roused to take action by sending delegates to Philadelphia with a mandate for putting a constitution together. Washington was asked to chair this convention. By voluntarily giving up his position at the height of his power four years earlier, Washington had implicitly reassured a public suspicious of authority that he was just the kind of principled and selfless leader they could trust to deploy power to further their, not his, interests. And he had given the world a chance to observe how people, when given the opportunity to choose for themselves, can act responsibly and for the common good.

The Colonies ratified the Constitution, and the congressional delegates unanimously elected Washington the first president of the United States, giving him the platform from which he would, over the next eight years, continue his effort to build a United States of America that could be a global beacon of freedom, justice, and equality for generations to come.

The Paradox of Freedom

But wait. How could America be proclaimed the land of the free when certain Colonies were practicing the institution of slavery? Washington himself inherited his first slave when he was 11, and over time, he owned more than 300. His views on slavery changed during the course of the American Revolution, and it was clear to him by the time he was president that this was a blot on the nation. “I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union …There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it.”

However, he understood that if he were to pursue abolition, the new, fragile fabric of the Union would be torn to pieces. So he chose to focus on strengthening the Union and surrendered the goal of abolition to the work of future generations. But he did make sure in his will that, upon his wife’s passing, his own slaves would gain their freedom.

In my leadership workshops with executives, we see this Washingtonian theme of surrender–of non-attachment to outcomes–play out again and again in the lives of great leaders. In pursuing bold visions, these leaders humbly recognize that they cannot control the precise contours of the outcome or bound the time frame in which the outcome will be achieved. They pursue their ambition doggedly on the outside, while on the inside they practice surrender. This lack of attachment allows them to operate flexibly, to listen to others with an open mind, to engage in constant readjustment, to limit their exposure to unfavorable conditions, and to capitalize on favorable shifts in the wind.

The Value of Faith

Practicing surrender isn’t that easy when you harbor strong ambition. In Washington’s case, it may be useful to add a postscript. As a deeply spiritual man, he saw the workings of a higher force behind all events. At a critical juncture in the Revolutionary War, he stated, “We safely trust the issue to Him … only taking care to perform the parts assigned to us.” Perhaps it was this faith that made him comfortable in surrendering ownership over the outcome even as he relentlessly executed the war.

Where his faith came from one cannot say, but it functioned as an ever-present shield that protected him, quite literally, on the battlefield. As a young man, Washington acquired a reputation for invincibility when he was serving in the Virginia Regiment–time and again, bullets would fly all around him and through his clothes only to have him escape unscathed. After one such miraculous outcome, he wrote, “By the all powerful dispensations of Providence, I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation, for I had four bullets through my coat and two horses shot under me, yet escaped unhurt, although death was leveling my companions on every side of me.” In recounting an unsuccessful attempt to kill Washington in a battle, an Indian chief was later moved to prophesize, “He cannot die in battle … Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man and guides his destinies–he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire.”

Perhaps if we, too, cultivate an indomitable faith – in our principles, our vision for the future, or a higher power – it will shield us in our everyday battles and give us the courage to practice the key of surrender when, from time to time, we find our ambition has transported us to the door of success only to find it locked.

For more information about the Institute for Personal Leadership and the leadership development programs for individuals and organizations, visit www.personalleadership.com.

This article was originally published in Inc. magazine – click here for the original.