Parisian macarons are everywhere.The classic French cookie — a sweet meringue-based confection made with egg white, icing sugar, granulated sugar, almond meal, and food coloring — can be found just as easily in upscale bakeries and desserts shops as it can on the shelves at Trader Joes.

Macarons have become an ideal gift to give a loved one and are such a deliciously decadent craze that they now have their own international holiday.

Oui, c’est vrai.

Mark your calendars: March 20th is worldwide Macaron Day.

The tradition was established in 2005 by local Parisian pastry shops and then spread to New York City. Nowadays, dozens of cities celebrate the French pastry each year, with many shops handing out a free macaron and donating a percentage of their proceeds to charity.

Yet, the history of this sweet treat standout is often misunderstood and its recipe confused with another popular variation — the macaroon, with two o’s.

To clear it all up, let’s first turn to Hollywood.

A Star Is Born

Macarons are arguably the most photogenic food on earth. The bright colors, the perfectly-symmetrical shape, the delicate appearance. They are a feast for the eyes and the taste buds alike.

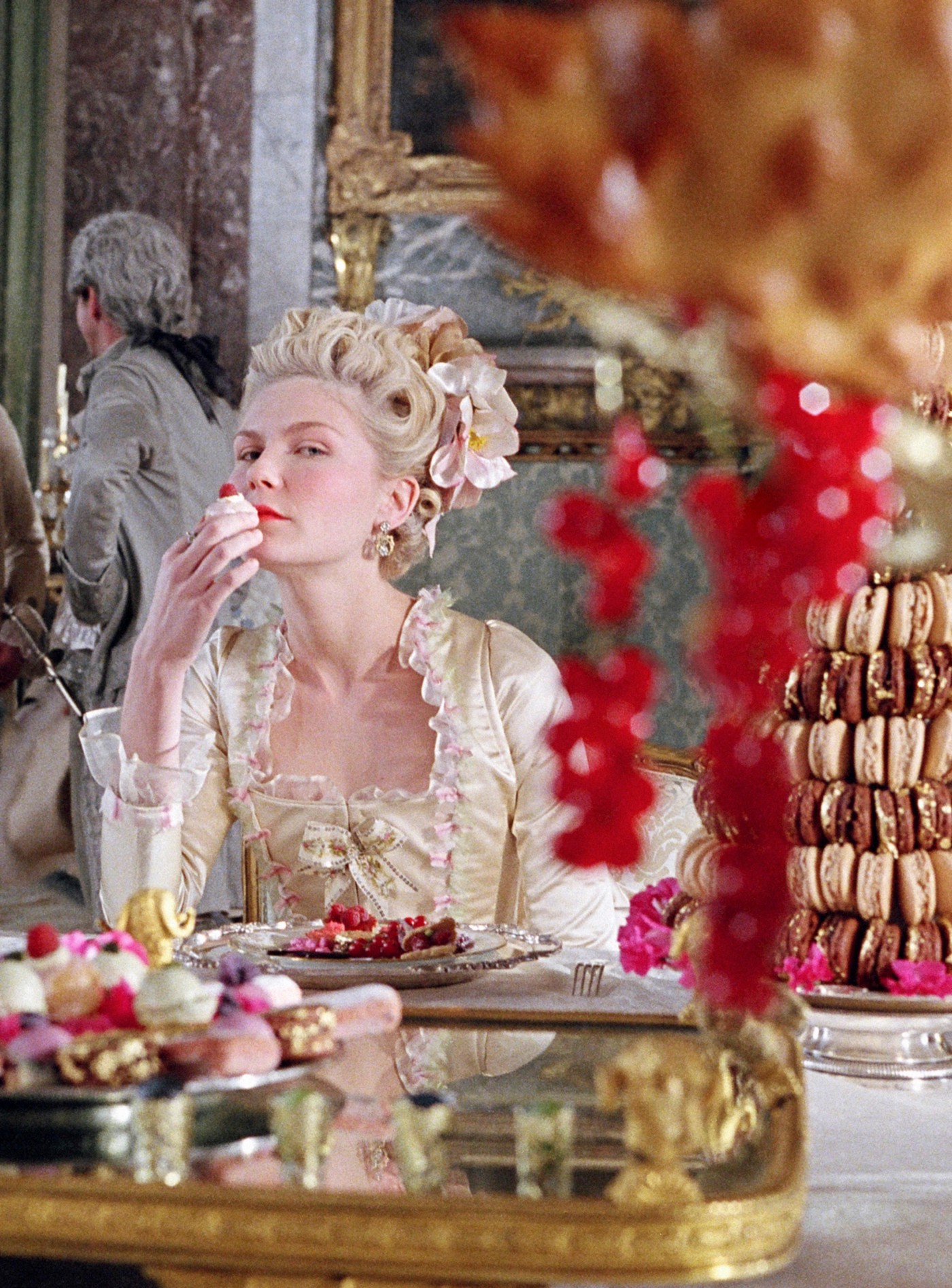

Quite fittingly, then, they were the backdrop to Sofia Coppola’s sumptuous 2006 film, Marie Antoinette, starring Kirsten Dunst. In the movie, Marie Antoinette is often pictured surrounded by sweets of all sorts, including macarons — in the rose tones we’ve come to associate with the doomed queen who supposedly once said, “Let them eat cake” to her starving peasant subjects.

Indeed, Coppola partnered with the famed Parisian patisserie and tea shop, Ladurée, to provide macarons for the movie. Laudrée is credited with inventing the Macaron Parisien, andCoppola reportedly handed her costume designer a box of pastel-colored Ladurée macarons saying, “These are the colors I love,” thereby inspiring the palette for the film.

According to Elisabeth Holder Raberin, owner of Ladurée, her chic patisserie is “forever linked” with Marie Antoinette and the Palace at Versailles.

Especially, she says, Versaille’s Le Petit Trianon:

“Le Petit Trianon . . . is so Marie Antoinette and feminine. She had her garden, flowers, milk, fresh produce: the ingredients for Ladurée quality today.”

A macaron star was born.

Except, they are not actually linked. Marie Antoinette and macarons.

Just as it’s now widely understood Marie Antoinette never uttered the words, “Let them eat cake,” it’s also a myth that she ever enjoyed a Parisian macaron.

Ladurée popularized the modern macaron, that’s true. However, Louis Ernest Ladurée opened his Parisian tea room in 1862, and it wasn’t until the 1930’s — nearly one hundred and fifty years after the death of Marie Antoinette — when his grandson, Pierre Desfontaines, put two macarons together with a cream filling in the middle and, voilà, invented the sandwich version that is so well-known today.

Marie Antoinette may have been familiar with an earlier version of the macaron, however, and this is where the story about the history of the macaron gets even more interesting.

To understand the true origins of the macaron we must turn our attention toward another queen. And toward Italy.

Best Supporting Actress

Catherine de Medici was an Italian noblewoman from a powerful banking family who married King Henry II of France and has gone down in the history books as the “foodie queen.”

She reigned as Queen of France from 1547 until 1559 and then as Queen Mother from 1559 to 1589, and therefore had forty years of great influence over French politics — and its cuisine.

According to Cook’s Info:

Catherine de Medici is credited with introducing many food innovations to France. She’s said to have taught the French how to eat with a fork, and introduced foods and dishes such as artichokes, aspics, baby peas, broccoli, cakes, candied vegetables, cream puffs, custards, ices, lettuce, milk-fed veal, melon seeds, parsley, pasta, puff pastry, quenelles, scallopine, sherbet, spinach, sweetbreads, truffles and zabaglione.

And, the macaron.

Like the myths surrounding Marie Antoinette, modern food historians have largely debunked the story that Catherine single-handedly revolutionized French cuisine and table manners.

Yet, through it all, the tale of the macaron persists since Catherine was known to (over) enjoy one particular sweet treat— a cookie made of almond paste.

Catherine’s cookie was different from the modern version in that it was made of almond paste, not almond flour, and was not filled with a delectable creamy ganache. It was really nothing more than a simple biscuit with a crisp crust and soft interior that she likely brought to France from Italy during the Renaissance.

A couple of centuries later, this would have still been the only version Marie Antoinette was familiar with.

In fact, the French word macaron either derives from the Italian verb, ammaccare, meaning “crunch” or “dent” (as in crunching almonds) or from the noun, maccheroni, meaning “macaroni,” which referred to any food, savory or sweet, made from something ground up, like a nut or wheat, for example.

This simple, sweet cookie had been produced in Venetian monasteries since the 8th century and was apparently nicknamed “priest’s bellybutton” on account of the pastry’s shape.

Since the 18th century, they are flavored with chopped bitter almonds or amaretto, a bitter almond liqueur, and called amaretti to distinguish from maccheroni, which today refers solely to the pasta.

Still, the macaron’s storied past goes back even further, to the Arab empire of the 600–700s. At that time, Arabic countries, like Syria, exported almonds and had a tradition of almond-based sweets such as fālūdhaj and lausinaj, which were almond-paste candies wrapped in dough.

According to a 2011 Slate article, as the Arab empire expanded into Europe:

The pasta and the almond-pastry traditions merged in Sicily, resulting in foods with characteristics of both. Early pastas were often sweet, and could be fried or baked as well as boiled. Many recipes from this period exist in both a savory cheese version and a sweet almond-paste version that was suitable for Lent, when neither meat nor cheese could be eaten.

So entwined are the gastronomical cultures, it’s actually not clear if the word, maccheroni, comes from Arabic or from the Italian dialect.

What is known is that almond sweets would spread across Europe, first to France through Catherine de Medici, then to Spain and England.

Evidence of the macaron appeared in the writings of Rabelais in 1552 and in English shortly thereafter (spelled with two o’s), right down to Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery — a handwritten family cookbook she brought from the old world to the new, which contains a recipe for the macaron that likely dates back to the 1600s and is almost identical to the Italian version.

So, even the first President of the United States quite possibly enjoyed a macaron from time to time.

Sister Act

In France, in particular, a number of cities lay claim to the macaron and offer up slight variations on the historic recipe, including Nancy, Boulay, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Satin-Émilion, Amiens, Montmorillon, Le Dorat, Sault, Chartres, Comery, Joyeuse, and Sainte-Croix.

All of these diverse French recipes are takes on the earlier, simpler biscuit-like cookie and have more in common with each other and with the Italian version than they do with the more recent colorful, perfectly symmetrical globally-marketed Parisian pastry.

One of the more legendary French spin-offs comes from the Lorraine city of Nancy in the northeast part of the country. According to the tale, two Benedictine nuns, Sister Marguerite Gaillot and Sister Marie-Elisabeth Morlot, sought asylum in the town of Nancy during the French Revolution (1789–1799), and paid for their housing by baking and selling macaron cookies.

(As an intriguing historical reference point, Marie Antoinette was executed by guillotine on October 14, 1793.)

The nuns became known as the “Macaron Sisters” (Les Soeurs Macarons), and in 1952 the city of Nancy honored the two nuns by naming the spot where they produced the macarons after them.

You can visit Maison de Soeurs Macarons in Nancy where the cookies are still made to the original recipe (egg whites, sugar, Provençal almonds), although the nuances of the ingredients and technique are still a well-guarded secret, bien sûr.

Plot Twist

In 1871, just fifty years before Laudrée gave Catherine de Medici’s almond cookie a facelift, Esther Levy published the first Jewish cookbook. In it, as a resident of Florida, she featured a recipe for macaroons — spelled with two o’s — using grated coconut instead of the traditional almond flour or paste.

Because the dietary restrictions of the Jewish holiday Passover prohibit the consumption of leavened baked goods, coconut macaroons were an instant success and gained enormous momentum in the food boom following WWI and WWII.

Happily, someone decided to dip them in chocolate at one point.

Meanwhile, Franklin Baker, a Philadelphia flour miller, was the first to discover that shipping shredded coconut was much more affordable and shelf-stable than shipping whole coconuts.

Kosher companies soon caught on and started mass producing the coconut version of the macaron.

The Nosher observes:

American Jews suddenly found it easier than ever to observe the holidays with ready-made and shelf-stable foods–the same Streit’s and Manischewitz tins and boxes that we recognize today.

La Fin

Today, tourists flock to Champs-Élysées to visit Ladurée, thanks in part to the movie but also because it has been long-adored for cultivating the Parisian tea room scene during the late 19th century. The salon de thé became the perfect chic meeting place for high society, and especially for women who could gather freely there.

Things aren’t quite as quaint as they once were, however. In 1993, Ladurée was taken over by Holder Group (owners of the bakery chain, Paul ), which set out on a luxury makeover and expansion of the chain, along with the industrialized production of the macaron. Oh well. C’est la vie.

Still, the quality and lore persist. And whether you fancy a traditional French or Italian macaron, a Parisian macaron, or a coconut macaroon, there are plenty of talented bakers and countless recipes for DIY as macarons have gone from fad to fixture. And the flavors are out of this world. Thai curry or matcha macaron anyone? How about a figgy almond or chai macaroon?

And the Oscar goes to?

Happy Macaron Day 2021.