Introduction

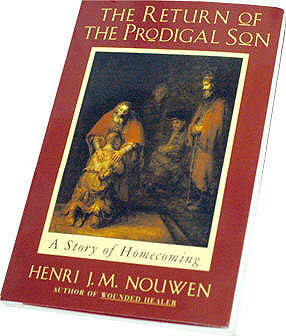

This book is a testimony to the power of art to inspire and transform lives. It’s really about the essence of Christianity condensed into one, simple parable about two very different sons and one very compassionate father.

The Prodigal Son is one of the best known of Jesus’ teachings, but Henri Nouwen uses an examination of Rembrandt’s rendition of the parable to help readers analyze many additional elements of spiritual transformation. Beyond a simple explanation of the prodigal son’s spiritual journey, Henri encourages readers to ponder the spiritual challenges faced by all the characters.

This is the first book I’ve read by Henri Nouwen, a beloved Dutch Catholic priest, professor, writer and theologian. His distinguished career teaching and lecturing at Notre Dame, Yale and Harvard divinity schools (as well as writing 39 books) took a dramatic turn in 1983 after he encountered Rembrandt’s ‘The Return of the Prodigal Son’ painting while visiting the L’Arche Daybreak community in France.

This is the first book I’ve read by Henri Nouwen, a beloved Dutch Catholic priest, professor, writer and theologian. His distinguished career teaching and lecturing at Notre Dame, Yale and Harvard divinity schools (as well as writing 39 books) took a dramatic turn in 1983 after he encountered Rembrandt’s ‘The Return of the Prodigal Son’ painting while visiting the L’Arche Daybreak community in France.

Rembrandt’s masterpiece made a deep spiritual impression upon Henri. Soon thereafter, he was given an opportunity to visit the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg to see the original painting. Following several days contemplating the spiritual implications of this painting upon his life Nouwen felt called to write this book.

“Rebrandt’s painting ‘set in motion a long spiritual adventure that brought me to a new understanding of my vocation and offered me a new strength to live it…Moving from teaching university students to living with mentally handicapped people was, for me at least, a step toward the platform where the Father embraces his kneeling son…the journey from teaching about love to allowing myself to be loved proved much longer than I realized,” writes Nouwen.

Following his encounter with the painting his spiritual journey was marked by three phases represented by the main characters of the parable and the painting – the younger son, the elder son and the father – which comprise the three parts of the book, which can also serve the reader as a pattern of better understanding the spiritual evolution within their own life. Henri’s conclusion: “I am the younger son; I am the elder son; and I am on my way to becoming the father…a father who asks no questions, wanting only to welcome his children home.”

It is said that the last words and works of a man often reflect his most important conclusions and contributions to posterity. The Return of the Prodigal Son is a perfect example; as one of Nouwen’s final and most popular books, as well as one of Rembrandt’s final and most popular paintings.

Part I – The Younger Son

“The younger one said to his father, ‘Father, give me my share of the estate.’ So he divided his property between them. Not long after that, the younger son got together all he had, set off for a distant country.” -Luke 15:11-13

To understand the full impact of this parable, Nouwen provides readers with the cultural context, explaining the taboo of a son requesting his inheritance prematurely as essentially saying that he wished his father were already dead. “The son’s ‘leaving’ in search of a ‘distant country’ is therefore, a much more offensive act than it seems at first reading. It is a heartless rejection of the home in which the son was born and nurtured,” writes Nouwen.

“Leaving home,” explains Henri, “is then, much more than a historical event, it is a denial of the spiritual reality that I belong to God with every part of my being, that God holds me safe in an eternal embrace…Home is the center of my being where I can hear the voice that says: You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests – the same voice that gave life to the first Adam and spoke to Jesus, the second Adam; the same voice that speaks to all the children of God and sets them free to live in the midst of a dark world while remaining in the light.”

Nouwen then reflects on the many times in his own life he has run off searching for love and acceptance in all the wrong places, which he says, “is the great tragedy of my life and of the lives of so many I meet on my journey”. His candidness prompts readers to also search their own heart, to ask if we too may have turned a deaf ear to the voice of God’s calling us his Beloved? According to Henri, “I leave home every time I lose faith in the voice that calls me Beloved…The world’s love is and always will be conditional.”

Nouwen then reflects on the many times in his own life he has run off searching for love and acceptance in all the wrong places, which he says, “is the great tragedy of my life and of the lives of so many I meet on my journey”. His candidness prompts readers to also search their own heart, to ask if we too may have turned a deaf ear to the voice of God’s calling us his Beloved? According to Henri, “I leave home every time I lose faith in the voice that calls me Beloved…The world’s love is and always will be conditional.”

Nouwen beautifully summarizes: “Looking again at Rembrandt’s portrayal of the return of the younger son, I now see now much more is taking place than a mere compassionate gesture toward a wayward child. The great event I see is the end of the great rebellion. The rebellion of Adam and all his descendants is forgiven, and the original blessing by which Adam received everlasting life is restored…these hands have always been stretched out – even when there were no shoulders upon which to rest them.”

The Prodigal Returns

“He wasted his money in reckless living. He spent everything he had. Then a severe famine spread over that country, and he was left without a thing. So he went to work for one of the citizens of that country, who sent him out to his farm to take care of the pigs. He wished he could fill himself with the bean pods the pigs ate, but no one gave him anything to eat. At last he came to his senses and said, ‘All my father’s hired workers have more than they can eat, and here I am about to starve! I will get up and go to my father and say, “Father, I have sinned against God and against you. I am no longer fit to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired workers.” So he got up and started back to his father. -Luke 15: 13-20.

In Rembrandt’s rendition of the prodigal son we see his emptiness, alienation, humiliation and defeat, which are well represented by his tattered clothing and shaved head – making his appearance worse than his father’s slaves. According to Nouwen, “Real loneliness comes when we have lost all sense of having things in common,” or being accepted in a community. Although the prodigal was lost and destitute; “be it his money, his friends, his reputation, his self-respect, his inner joy and peace – he still remained his father’s child.”

“The younger son’s return takes place at the very moment that he reclaims his sonship, even though he has lost all the dignity that belongs to it…it seems the prodigal had to lose everything to come into touch with the bedrock of his sonship – the ground of his being…One of the greatest challenges of the spiritual life is to receive God’s forgiveness…Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think about his love as conditional,” reflects Nouwen.

“The younger son’s return takes place at the very moment that he reclaims his sonship, even though he has lost all the dignity that belongs to it…it seems the prodigal had to lose everything to come into touch with the bedrock of his sonship – the ground of his being…One of the greatest challenges of the spiritual life is to receive God’s forgiveness…Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think about his love as conditional,” reflects Nouwen.

Henri challenges readers to consider a further metaphor hidden within this beloved parable: “Jesus himself became the prodigal son for our sake. He left the house of his heavenly Father, came to a foreign country, gave away all that he had, and returned through his cross to the Father’s home…not as a rebellious son, but as the obedient son, sent out to bring home all the lost children of God…Jesus, who told the story to those who criticized him for associating with sinners, himself lived the long and painful journey that he describes.”

WOW, great insight!

“Nouwen concludes Part I with this panoramic perspective, “The young man being embraced by the Father is no longer just one repentant sinner, but the whole of humanity returning to God. Thus Rembrandt’s painting becomes more than the mere portrayal of a moving a parable. It becomes the summary of the history of our salvation.”

Part II – The Elder Son

“In the meantime the elder son was out in the field. On his way back, when he came close to the house, he heard the music and dancing. So he called one of the servants and asked him, ‘What’s going on?’. ‘Your brother has come back home,’ the servant answered, ‘and your father has killed the prize calf, because he got him back safe and sound.’ The older brother was so angry that he would not go into the house; so his father came out and begged him to come in. But he spoke back to his father, ‘Look, all these years I have worked for you like a slave, and I have never disobeyed your orders. What have you given me? Not even a goat for me to have a feast with my friends! But this son of yours wasted all your property on prostitutes, and when he comes back home, you kill the prize calf for him!'” – Luke 15: 25-30

Although the return of the prodigal son is the central event in both Christ’s parable and Rembrandt’s painting, Nouwen sheds new light on the elder son in Part II of the book. Perhaps in part, because a close friend of Henri told him that his life more closely resembled the elder son than the prodigal son, which sparked fresh spiritual reflection upon the topic.

Nouwen admits, “It is hard for me to concede that this bitter, resentful, angry man might be closer to me in a spiritual way than the lustful younger brother. Yet the more I think about the elder son, the more I recognize myself in him.”

Nouwen admits, “It is hard for me to concede that this bitter, resentful, angry man might be closer to me in a spiritual way than the lustful younger brother. Yet the more I think about the elder son, the more I recognize myself in him.”

Nouwen explains why the elder son, who never left home, was lost too – but he was estranged from his father in a different way; “The lostness of the resentful ‘saint’ is so hard to reach precisely because it is so closely wedded to the desire to be good and virtuous.”

Instead of gratitude for the return of his wayward brother, the elder son’s resentment wells up within and cuts off his ability to participate in the joyful feast. “He was angry then and refused to go in.” As Nouwen puts it, “Joy and resentment cannot coexist. The music and dancing, instead of inviting to joy, become a cause for even greater withdrawal.”

Henri continues, “There are many elder sons and elder daughters who are lost while still at home…characterized by judgment and condemnation, anger and resentment, bitterness and jealousy – that are so pernicious and so damaging to the human heart.”

Deeper reflection upon the the parable clarifies that both sons have good and bad character traits – which are equally accepted by their father. “The father only is good. He loves both sons. He runs out to meet both. He wants both to sit at the table and participate in his joy…What is so clear is that God is always there, always ready to give and forgive, absolutely independent of our response. God’s love does not depend on or repentance or our inner or outer change,” writes Nouwen.

“The story of the prodigal son is the story of a God who goes searching for me and who doesn’t give up until he has found me. “Without trust, I cannot let myself be found. Trust is that deep inner conviction that the Father wants me home…There is a very strong, dark voice in me that says the opposite…without discipline, I become prey to self-perpetuating hopelessness,” concludes Nouwen.

“The return of the elder son is becoming as important to as, if not more important than, the return of the prodigal son…Jesus is himself not only the younger son, but the elder son as well. He has come to show the Father’s love and to free me from the bondage of my resentments.”

“The words of the father in the parable: ‘My son, you are with me always, and all I have is yours’ express the true relationship of God the Father with Jesus his son… As I look again at Rembrandt’s elder son, I realize that the cold light on his face can become deep and warm – transforming him totally – and make him who he truly is: ‘The Beloved Son on whom God’s favor rests.'”

Part III – The Father

“While he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him. . . the father said to his servants, ‘Quick! Bring the best robe and put it on him. Put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the fattened calf and kill it. Let’s have a feast and celebrate . . . So his father went out and pleaded with him . . . The father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’” -Luke 15:20-24, 31-32

The majesty of Rembrandt’s painting and Christ’s parable come to a crescendo in Part III of the book, as readers are led by Nouwen to focus on the compassion and love of the father as the Christian’s ultimate goal. “What gives Rembrandt’s portrayal of the father such an irresistible power is that the most divine is captured in the most human.”

The majesty of Rembrandt’s painting and Christ’s parable come to a crescendo in Part III of the book, as readers are led by Nouwen to focus on the compassion and love of the father as the Christian’s ultimate goal. “What gives Rembrandt’s portrayal of the father such an irresistible power is that the most divine is captured in the most human.”

In his final rendition of the prodigal son painted in 1669, Rembrandt chose a nearly blind old man to represent the father – in contrast to his earlier rendition painted as a young man in 1632. Perhaps because his own life had moved toward the shadows of old age. Henri reflects, “As the light of his interiorizes, he begins to paint blind people as the real see-ers…The inner light-giving fire of love that has grown strong through the artists many years of suffering burns in the heart of the father who welcomes his returning son.”

“Rembrandt’s hands had painted countless human faces and human hands. In this, one of his last paintings, he painted the face and hands of God…Rembrandt was the son, he became the father, and thus was made ready to enter eternal life.”

Nouwen sees the true center of the painting to be the hands of the father, gently resting on the prodigal son’s shoulders. “…in them mercy become flesh; upon them forgiveness, reconciliation, and healing come together, and through them, not only the tired son, but also the worn-out father find their rest.”

Our Heavenly Father Seeks the Lost

All three of Jesus’ parables in Luke 15 illustrate a proactive God seeking; the lost coin, the lost sheep, and the lost sons. “It was not I who chose God, but God who first chose me…I am beginning now to see how radically the character of my spiritual journey will change when I no longer think of God as hiding out and making it as difficult as possible for me to find him, but instead, as the one who is looking for me while I am doing the hiding.”

“For a very long time I considered low self-esteem to be some kind of virtue,” confides Nouwen, “but now I realize that the real sin is to deny God’s first love for me, to ignore my original goodness…I do not think I am alone in this struggle to claim God’s first love and my original goodness.”

Henri underlines the divine eagerness to embrace all God’s children, saying “The father does not even give his son a chance to apologize. He pre-empts his son’s begging by spontaneous forgiveness and puts aside his pleas as completely irrelevant in the light of the joy of his return.”

Jesus often speaks of joyful dining at a banquet table with every hungry soul, to illustrate the availability of the Kingdom of God to all. “Rejoice with me’ the woman says, ‘I have found my lost coin,’, ‘Rejoice with me,’ the shepherd says, ‘ I have found my lost sheep,’ ‘Rejoice with me,’ the father says, ‘this son of mine was lost and is found.'”

In the concluding chapter “Becoming the Father,” Nouwen issues his final challenge to readers. “But there is more…when the prodigal son returns home, he returns not to remain a child, but to claim his sonship and to become a father himself…Having reclaimed my sonship, I now have to claim fatherhood…I now see the hands that forgive, console heal and offer a festive meal must become my own.”

From Sonship to Fatherhood

“Rembrandt’s painting, and his own tragic life, offered me a context to discover that the final stage of the spiritual life is to so fully let go of all fear of the Father that it becomes possible to become like him…to live out his divine compassion in my daily life.”

“Perhaps the most radical statement Jesus ever made is: “Be compassionate as your Father is compassionate.” … “Jesus is the model for our becoming the Father…His unity with the Father is so intimate and so complete that to see Jesus is to see the Father…’Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father,’… Jesus shows us that true sonship is.”

“In this perspective, the story of the prodigal son takes on a whole new dimension… Jesus becomes the younger son as well as the elder son in order to show me how to become the Father. Through him I can become a true son again and, as a true son, I finally can grow to become compassionate, as our heavenly Father is.”

“Looking at Rembradt’s painting of the father, I can see three ways to a truly compassionate fatherhood:grief, forgiveness, and generosity…Grief asks me to allow the sins of the world to pierce my heart and make me shed tears…forgiveness that is unconditional and does not demand anything for itself…generosity which pours himself out for his sons.”

“Looking at Rembradt’s painting of the father, I can see three ways to a truly compassionate fatherhood:grief, forgiveness, and generosity…Grief asks me to allow the sins of the world to pierce my heart and make me shed tears…forgiveness that is unconditional and does not demand anything for itself…generosity which pours himself out for his sons.”

“These are three aspects of the Father’s call to BE home. As the Father, I am no longer called to COME home as the younger or elder son, but to BE there as the one to whom the wayward children can return and be welcomed with joy…indeed, my youth is over…As the Father, I have to dare to carry the responsibility of a spiritually adult person…”

“Then both sons in me can gradually be transformed into the compassionate father. This transformation leads me to the fulfillment of the deepest desire of my restless heart. Because what greater joy can there be for me than to stretch out my tired arms and let my hands rest in a blessing on the shoulders of my home-coming children?,” Henri concludes the book with this insightful question.

Conclusion

Nouwen’s book is both autobiographical and devotional. But, it is more than just a devotional book on the Biblical parable of the prodigal son; it is a devotional book on Rembrandt’s ‘Return of the Prodigal Son’ painting as well. He provides an illuminating commentary of Rembrandt’s painting that was only possible in combination with his spiritual insight into the parable. His analysis offers readers a new perspective on this classic parable, revealing why this parable might well have been called “a parable of the lost sons” or “a parable of a Father’s compassion”.

Neither the parable nor Rembrandt’s painting clarify whether the elder son eventually confesses his sin or asks the father’s forgiveness. “Unlike a fairy tale, the parable provides no happy ending. Instead it leaves us face to face with one of life’s hardest spiritual choices: to trust or not trust in God’s all-forgiving love,” says Nouwen.

Only one thing is certain; the Father’s heart of limitless mercy. I strongly recommend this book for young and old alike. Likely it will end up in my kids and Gkids stocking this Christmas. In fact, I was so moved by both the book and the painting that I decided ordered a print of Rembrandt’s painting from art.com, which presently hangs in my dining room as a daily reminder of the limitless compassion of our loving Creator.