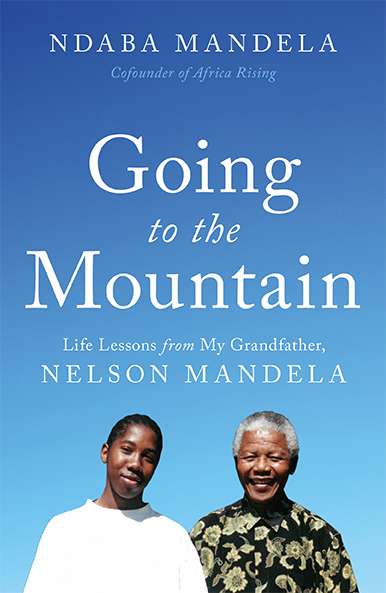

Adapted from GOING TO THE MOUNTAIN by Ndaba Mandela.

I went down the hall and paused at the door to Madiba’s office where he was sitting in a chair reading. “Granddad?”

“Ndaba.” He smiled and motioned me to come in. “How are you today? How was school?”

“It was okay. But…Granddad, I lost my jersey. I need another one.”

“Oh, Ndaba.”

“I’m sorry, Granddad.”

After the stern talk about personal responsibility, reminding me how many people in the world had nothing and no one to ask if they needed the most basic necessities, he said, “I’ll tell Rochelle to go with you and buy it tomorrow. And I expect you to take better care of this one.”

Head bent by shame, I said, “I will. I’m sorry, Granddad.”

“All right. Go to bed now.”

I went to my room, feeling like the exchange had gone as well as it could have. “No blood, no foul,” as they say. Until a few weeks later when I lost my jersey again. I was shaking in my shoes when I had to go tell him, trying to come up with any possible Plan B. Run away. Go to a different school. Try to find any conceivable way to blame it on someone else. Try to look as pathetic as possible and stir sympathy.

“Granddad?”

“Ndaba…” When he glanced up, I suppose he noticed I was practically shrinking inside out. “What is it?”

“I’m sorry,” I said wretchedly. “I lost my jersey again.”

There was no sympathy. He was straight up furious. The personal responsibility talk went to another level, and at the end of it, he didn’t offer up Rochelle getting me another replacement.

“Clearly,” he said, “you didn’t take it seriously when I told you to take better care of this one. That’s how much you appreciate your home and all the things you have here—your clothes, your games, your room that I must tell you every day, ‘Clean this room, Ndaba. Pick up your clothes.’ Well, you know what? Tonight you sleep outside.”

I stood there, gobsmacked.

“Go outside!” he thundered. “You’re not welcome in this house tonight.”

What could I do? I slunk down the hall and out the door. The shadows were already long. It was dusk. It would be dark soon. The yard was surrounded by a high wall. I figured if bad guys tried to climb over it, the security people would come out and stop them. Theoretically. I found a fairly comfortable spot on the grass beneath a blue guarri tree, but I wondered if there might be snakes in the sneezewood trees and wisteria surrounding the pool. It got dark. The heat of the day faded off. I sat there shivering, arms hugged tight around my knees. I just about jumped out of my skin when I heard Mama Xoli call my name from the kitchen door.

“Ndaba?”

Startled but relieved, I ran to meet her as she walked out under the yard light. I assumed she’d come to take me inside for supper. That was not the case.

She handed me a blanket and said, “Madiba asked me to give this to you.”

I tried to say “thank you,” but there was a lump in my throat. He was serious. He was going to make me stay out here all night in the cold with no food and probably poisonous snakes and potential thugs and assassins maybe climbing over the wall. Mama Xoli went back inside, and I swallowed hard. My eyes were burning, but allowing myself to cry wouldn’t have done me any good. I wasn’t one to cry, even at that age. Maybe for something physical, like the time my friends and I faced down the tear gas-belching Hippo, but this was a thousand times worse than that, because I was alone, and I’d made my granddad so angry, and sooner or later I’d have to face him again. So be it. Come what may, I was not going to cry. Because a Xhosa man endures. This is what we say when we greet each other.

“Hello,” a guy says. “How are you?”

“Ndi nya mezela,” says the other guy. I am enduring.

I found a good spot to sit down and wrapped the blanket around my shoulders. Birds settled in the trees, whistling softly every time a breeze moved through the branches. After a while, I saw Mama Gloria inside the kitchen window, washing dishes and hanging the pots and pans. Supper was over. My stomach was hollow with hunger. I would have been glad for a bowl of the old rice with ketchup. Beetles chirped in the hedges. Somewhere far away a dog was barking in the cool darkness. I started to drift off but jerked awake when I heard heavy footsteps coming toward me. I scrambled to my feet and saw the Old Man crossing the lawn.

“Ndaba?”

“Yes, Granddad?”

“If you ever lose your jersey again,” he said, “you really will sleep outside. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Granddad.”

“Let’s go in.”

He headed back toward the house, and I fell in beside him, trying to keep up with his great long stride.

“My father loved and respected his children, but he did not spare the rod. He maintained discipline.” He opened the kitchen door and shooed me into the entryway. “Go inside and have dinner and then go to bed.”

I was never so glad to be at that kitchen table. And I never lost another school jersey. Since Lewanika and Neema came along, I hear myself saying a lot of the same things my granddad said to me when I was a boy. In fact, Lewanika’s mother called me not long ago and said, “I don’t know how he managed it, but your son has already lost his school jersey.”

He was just starting his first year at big boy school. So that didn’t take long. I laughed long and hard.

“What’s so funny?” she asked.

“Nothing. Tell him if it happens again, he’ll sleep outside.”

Adapted from the book GOING TO THE MOUNTAIN by Ndaba Mandela. Copyright (c) Ndaba Mandela by Hachette Books. Reprinted with permission of Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.