It’s about as close as anywhere in the US gets to ‘hygge’. It’s a place of sharing, equality and close contact and it’s also the most isolated community in the United States. That said, there is occasionally cell phone service.

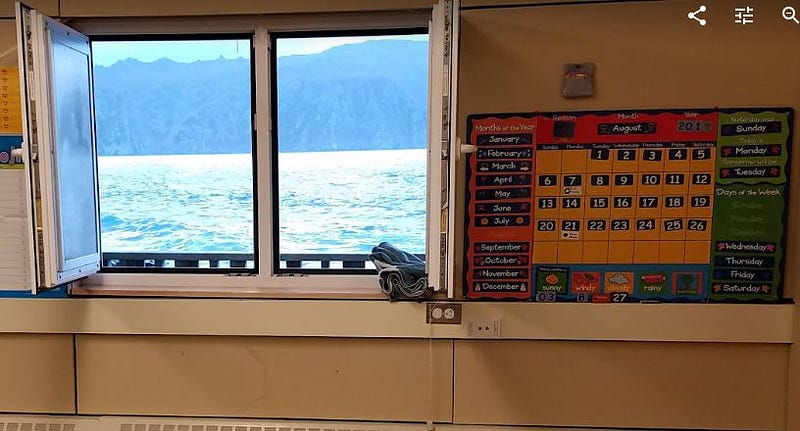

The location is the Bering Strait, the outermost reaches of Alaska, 140 miles Northwest of Nome [home of the Discovery Channel’s Bering Sea Gold], less than a mile East of the International Date Line and the Russian border.

The only way to get here is an hour and a half ride on a freight helicopter from Nome that delivers the mail, food and other supplies to the Native village once or twice a week, weather permitting, and the weather doesn’t often permit…

So how does an American community keep its spirits up when it’s living on an almost barren pile of rocks that for most of the year is either covered in fog or ice, and is so far from the rest of the US that it’s closer to Siberian Russia? Here’s a rundown of how the Eskimos keep their five happiness muscles in good shape….

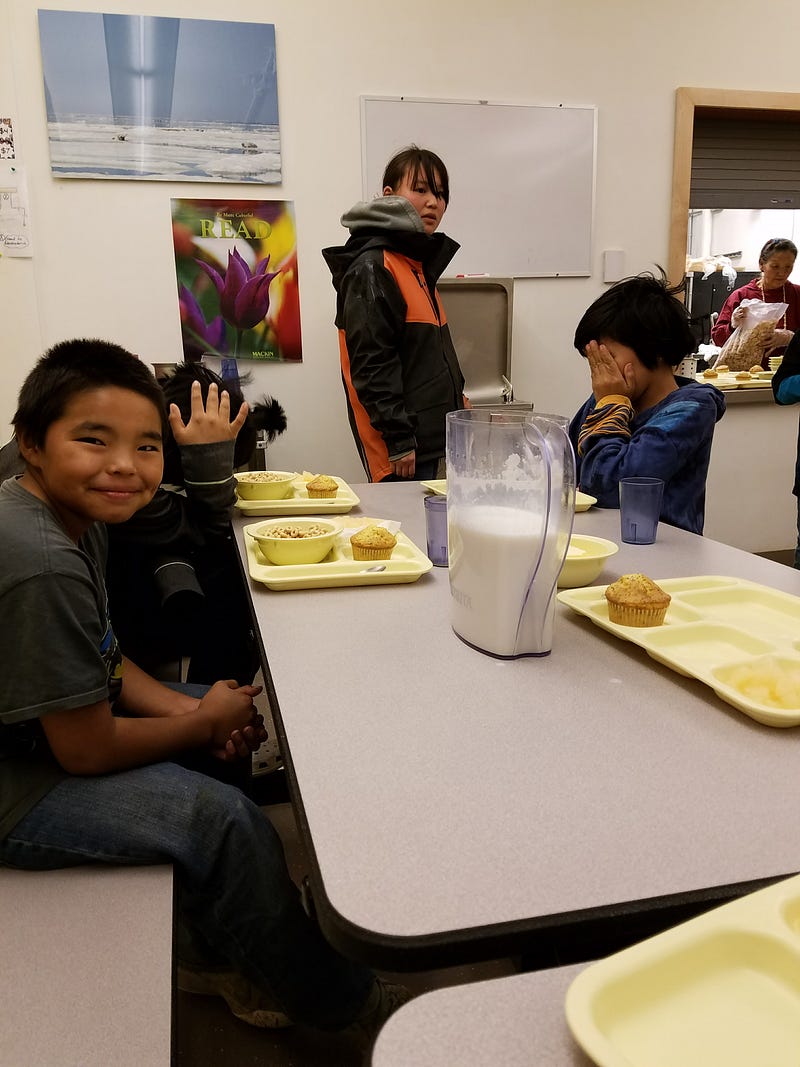

Eskimo happiness muscle number 1: Kindness: As we landed, around 20 villagers (Diomede has a population of about 100 of which 95% identify themselves Eskimos) gathered around the helipad, 20 feet above the waves. They grabbed about thirty bags and boxes from the chopper and carried them on their shoulders along a path towards the houses and the school; many hands making light — unpaid — work.

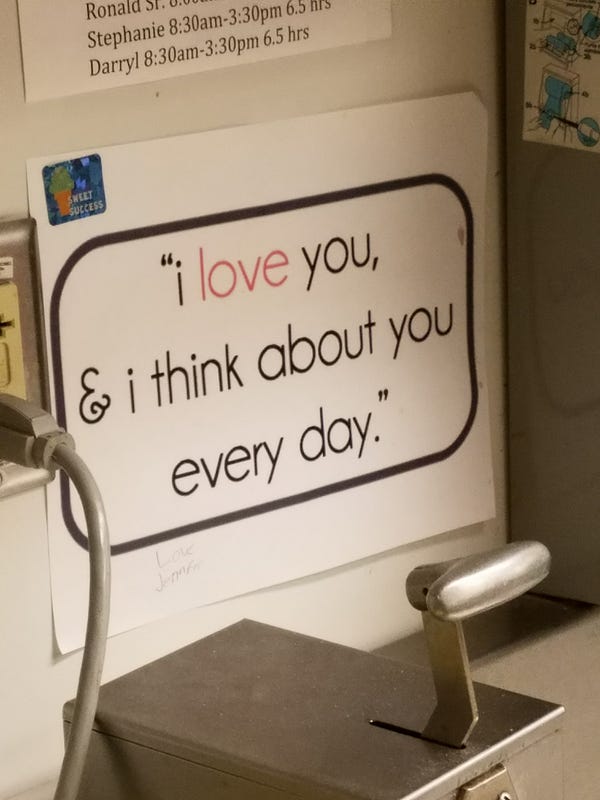

As I stared across the 2-mile channel to the cliffs of Russia, Ron walked up to me with a grin. Ron is a well weathered thirty-nine year old Eskimo who smiles often. His father is the school janitor and his mother, the dinner lady. I even saw Ron’s daughter helping her grandfather in the rain to reinforce the sea wall in front of the school.

Ron told me that as the villagers become more accustomed to food sold at the island’s ‘Native Store’, people now hunt less — although while I was there I met several who had been foraging the cliffs for Eskimo Potatoes. Four of the islanders also have small fishing boats but who catches what doesn’t matter when concept of ownership is as watery as the surroundings…

‘Even if you follow a boat out and you don’t catch anything but the other boat does, they will share their catch with you. If you go to the mainland, the boat captain takes everything but here the whole boat shares’ — Ron

‘I’m going to get coffee. ‘Do you want some?’ asked Ron. He smiled. We walked about 30 feet to Washeteria, the island’s coin laundry, which doubles as a brew station for the locals. Once inside one of the teenagers who wore yet another smile and a hoodie printed with the words ‘Keep One Rolled’, started to fix us a fresh brew.

Coffee was a dollar, and Ron offered to pay. A couple of sips in and our chat was cut off — A woman in her early thirties had just walked in and began crying as she looked at her phone. I asked her if she was alright. She said no and walked back outside…

Eskimo happiness muscles 2 & 3: honesty and awareness

‘Something’s happened. They will call a meeting,’ said Ron. Sure enough by the time we got outside, villagers were already starting to shout to each other across the paths between the houses. I heard a father calling to his son to get his brother. Ron thinks someone on the mainland has either died or gone to hospital, but seems unphased and continues. He tells me as he rests on one of the boats that he sometimes feels frustrated that he can no longer hunt because of his back and limited movement in his arms.

When Ron feels this frustration he calls up the Nome police station to exercise his honesty muscle by expressing some resentments. Ron says he was repeatedly pepper sprayed by a cop, who used the spray to wake him up when he passed out on a street in Nome [after a few drinks]. The cop and his partner took Ron to the hospital to wash the spray off, then forced him into the footwell behind one of the seats of the police car, at which point Ron thinks he sustained the injuries to his back and shoulders.They took Ron to Nome jail where the cop pepper sprayed him again. Then back to the hospital for another rinse, then back to jail. Ron says that at this point the second policeman felt left out so he gave him a pepper spraying too.

Throughout the story Ron smiles as he talks with the soft melody of the Eskimo accent.

He reassures me that the ‘bad cop’ is now retired from Nome police and although Ron is still angry with him, he maintains a level of awareness of why the cop did it: As a kid, the policeman was one of the few non-natives in town and the majority picked on him. As soon as he became old enough, he joined the police force and started acting out to validate his ego.

Eskimo happiness muscle 4: tolerance and curiosity (aka the wonder muscle)

Up until a few years ago the islanders tossed their garbage bags into the ocean. But Russian soldiers started to complain that it was washing up on their shoreline two miles away, so now the trash is incinerated or piles up. Big Diomede, the neighboring Russian island, is a military base. The former residents were displaced during the Cold War, when most of the families moved to here to Little Diomede, the others to Siberia. Up here, Russia and the United States mean little other than an invisible border that prevents people from visiting their families.

Ron’s father tells me he and his father were the last on the island to make skin boats — the traditional Eskimo vessel for hunting. The last skin boats were wiped out when they left them on the shore just before the onset of winter. Overnight the sea ice arrived and crushed the boats against the rocks. But life went on and eventually they replaced the skin boats with the four modern boats from the mainland.

The crosses are superfluous: the ground is so hard the islanders cannot bury their dead. That doesn’t stop them putting the bodies in coffins that rest on the rocks of the hillside.

An as yet unweathered white coffin is clearly visible a couple of hundred yards up the slope to the South East. Inside, a teenager who died after falling out of a boat without a life jacket. Most of the islanders do not know how to swim. I noticed detachment from the concepts of loss and death, whether it was towards skin boats or people. Staying connected to the community and what’s happening in the immediate present — whether that’s the twenty walruses we saw swimming past or the pod of orcas the day before, or whether the helicopter will be coming today or just whether it’s time for another cup of coffee — quickly blow away the mental weather of frustration or loss. And the wind here is strong, most of the time.

I had sent copies of my children’s book Puptrick tells a lie and learns to bark to the school in advance of my trip and while wandering the corridor I overheard the story being read aloud in the classroom. The teacher, Rob invited me into class to talk to the children, many of whom I had already met when I kayaked off the island the day before — who laughed and grabbed me or jumped on my back and asked for my autograph along with a string of questions about where I lived and what it was like and if I was famous.

Eskimo happiness muscles number 5: Courage (and love) Ron smiles and puffs on a cigarette as he tells me a story of a boat on its way back to land, full of fish.The waves began breaking over the side of the boat and it started to sink. One of the Eskimos stuck his head over the side into the water and called the orcas. Ron and Keep One Rolled swear that the orcas appeared and formed a wave barrier along the side of the boat preventing it from taking on more water as they escorted it to shore.

‘So that community has the orcas respect. You just have to respect mother nature’.

After lunch the kids wanted me to join them in the gym for PE, which took the format of dodgeball. No fear in any single child. As a Brit, it was pretty new to me. Imagine a 39 year old man being intimidated by a group of under 10’s and you’d be close. That said, during my two days at the school there was no evidence of any bullying, no ostracized kids, probably just because of the levels of contact from living, playing, eating and sleeping all within a hundred yards of each other day in, day out. And when we played dodgeball in the gym, every single child was laughing. All appeared genuinely happy.

The personalities were varied and authentic from the quiet, introspective and bookish to the bold boy who kept asking me to arm wrestle, to the joker, to a girl who pretended to be a cat and leaping from rock to rock while meowing like a feline banshee (you can see and hear her in this video of the kids playing around me as I got my kayak ready for the trip towards Russia) to a girl who laughed almost nonstop. No child was afraid to be different. Difference here is embraced, not feared.

The people of Little Diomede are hardy enough to live on rocks surrounded by sea-ice for a long winter but they are also warm people who accept others and their own fate with a smile and a melody. Outside dodgeball, there’s no competition and little ego. Perhaps, and just maybe, that’s why most people I met on this island seemed if not happy, then at least content. Winter is coming but that doesn’t worry the residents of Little Diomede.