Mary had dark hair and huge soulful eyes that were more ebony than brown. Her mother gave birth to her at home when she was forty years old, a feat at any age and a testament to a hearty stock of women known for their quiet strength. There was a significant gap in age between Mary and the next sibling, making her by default the cherished baby girl in a family of four.

She was inextricably close to both parents, but had a special bond with her Dad. He doted on her and she adored him for his indulgent ways: “You wanna fresh tomatoes? I get you fresh tomatoes,” her father would say in his thick Italian accent, rambling out to the garden, and once leaning over the fence to borrow some from a neighbor when it was determined that they were more perfectly ripe. This memory would stick with her even more than the other hundreds of times he would bring her fresh tomatoes as added proof that he would do anything for his baby girl.

Her mother was a strong, independent and savvy business woman with a big heart for helping anyone who might be down on their luck — the pregnant girl that got kicked out of her home, the young man fresh from Italy who needed help finding work. She was Mary’s fiercest protector and biggest champion; and Mary would forever be inspired by her compassion and ancient wisdom.

I never knew her father and was just a baby when her mother died. I have their photographs, black and white and stoic, to remember them by.

When Mary Zuani married Bill Cooper, she told him that she wouldn’t give up until she had a baby girl. And despite two miscarriages and approaching forty years of age, she was determined to have me. There’s a significant gap between myself and my two brothers, making me by default the cherished baby girl in a family of three.

I was undeniably close to both of my parents, but I was Daddy’s girl. It was a love so great that a psychiatrist had once commented that he thought my father “loved me too much.” To which my father replied, “That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard — loving a child too much.” My father, a physician himself, denounced him as a quack, which back in the day was the epitome of insults from one doctor to another.

My mother and I, both strong and fiery and independent, could reach an impasse; whereas my father was always the calm voice of reason, the warm gentle waters in which to float upon. He understood me to my depths somehow in a way my mother couldn’t see. And he was always — always — a soft place to land.

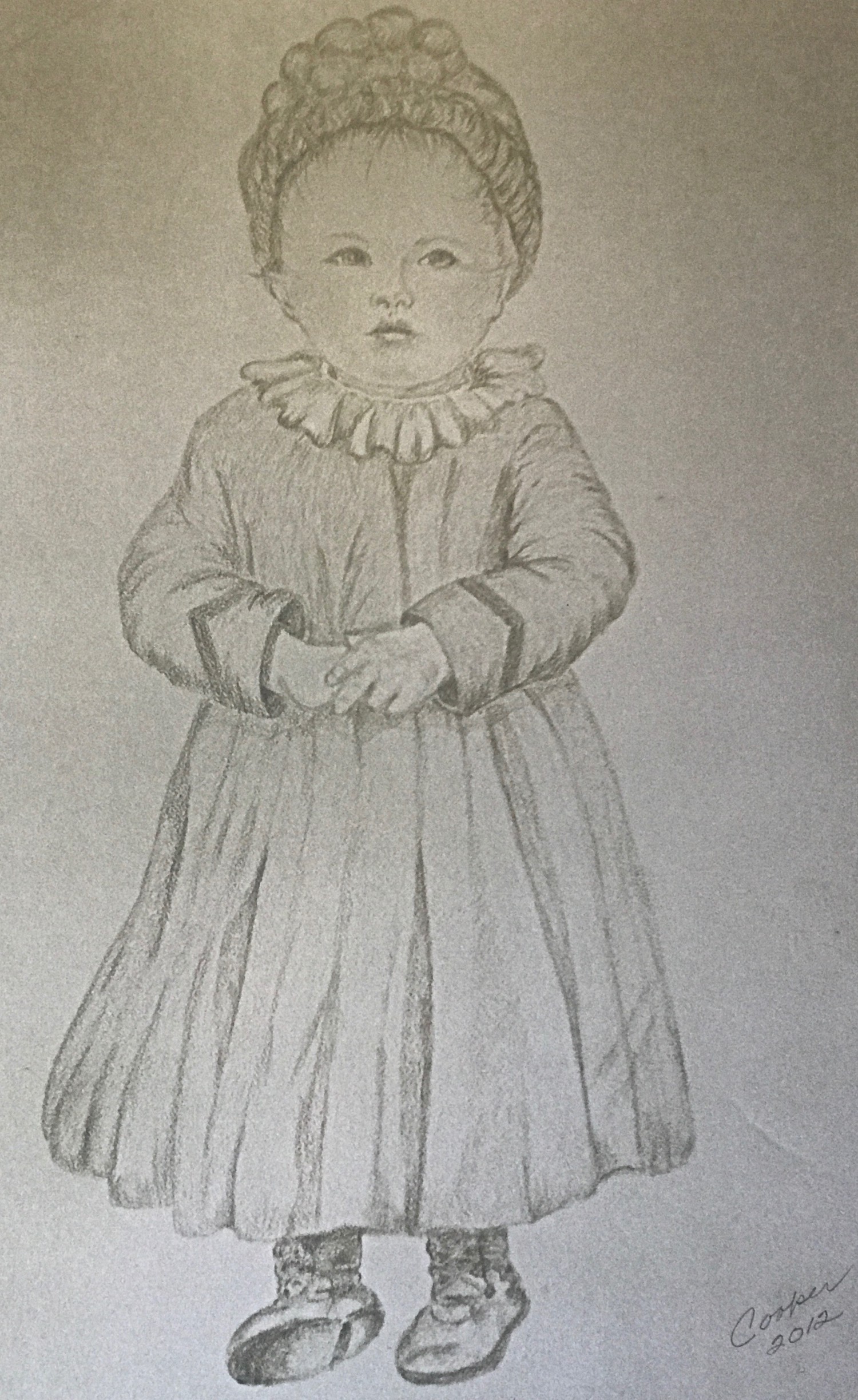

Still, my mother was my fiercest protector and biggest champion. I leaned on her often for her strength and ancient wisdom. She was an artist — a creative — who changed interests and mediums on whims and often. Painting one year. Clay the next. Knitting in the 70’s when afghans in three different block colors were all the rage. I still have one in brown and orange and white stripes, peaked in angles like Charlie Brown’s shirt. She always had her nose in a book and it was completely acceptable to bring one to the dinner table. I started with Nancy Drew, moved onto Judy Bloom, and for as long as I can remember, have always been reading something.

After a decade of trying to have a child, I was close to forty and teetering on being considered by some too old to adopt. I told my husband I wouldn’t give up until we had a baby girl. When we got the call about a pregnant woman in Pennsylvania, we didn’t know the sex. “Yes, yes, of course yes. No matter the sex. No matter at all.” A card arrived in the mail several weeks later, sent by the birth mother. When I opened it two little pieces of paper drifted to the floor. They were ultrasound images. It was a girl.

Our daughter was my constant inseparable companion up for any adventure the two of us might conjure up, until the age of nine. Then she became a Daddy’s girl. She adores and looks up to her father in a way that moves me to tears and often. If I didn’t remember deeply this dynamic in my own childhood, I would be terribly envious of her shift of allegiance, but I hold sacred the tight bond between a father and a daughter.

We didn’t see the dyslexia diagnosis coming as neither of us are dyslexic. We turned her learning over to more skilled experts and I held my breath for awhile to see if she would ever read for the sheer pleasure of it all. Like my mother, I couldn’t imagine life without books. And I didn’t want to imagine her life without them either.

She started with Nancy Drew, then Harry Potter and now Percy Jackson. She reads next to me in the car in a silence that is frequently interrupted by big laughter, then she will turn to me to share the story. She brings a book to the dinner table all the time, although it sits beside her so we can talk. She is never not reading something and prefers to be lost in a book to just about anything. She is collecting her own library of books that are important to her. She wants to keep them for her own children one day.

This summer she’ll turn thirteen and by now I’ve gotten accustomed to her choosing my husband over me. I know I’ll be back in favor in a few years. Then she will recognize me as her fiercest protector and her biggest champion; the one to turn to for ancient wisdom and strength.

I began to write this on the occasion of my mother’s birthday and by the time I finished it, the third anniversary of her death had arrived. I inherited my mother’s vast library of books when she died, and lovingly held onto those that meant the most to her, the one’s my father would carefully wrap for her on her birthday or Christmas, meticulously creasing the paper and making a ribbon with surgical precision, then hiding it away high in his closet until it was time.

When my father died nine years ago, I didn’t understand death. Yet like any death, it was an invitation to a spiritual awakening. One I embarked on with sincerity, determination and unwavering commitment. In this way my two greatest teachers — my mother and father — remained my greatest teachers even after they died. I can now close my eyes and feel them with me. We are not apart. Our love forever binds us together. Our stories have been woven into tapestries passed down through the generations and share the same threads that connect us all. Love. How it is given and demonstrated and permanent. Love. An energy so powerful it can be felt beyond the stars. Love. Not even death can take it away.

______________________________________________________________

#weekly prompt

[email protected] or facebook or instagram or twitter

Originally published at medium.com