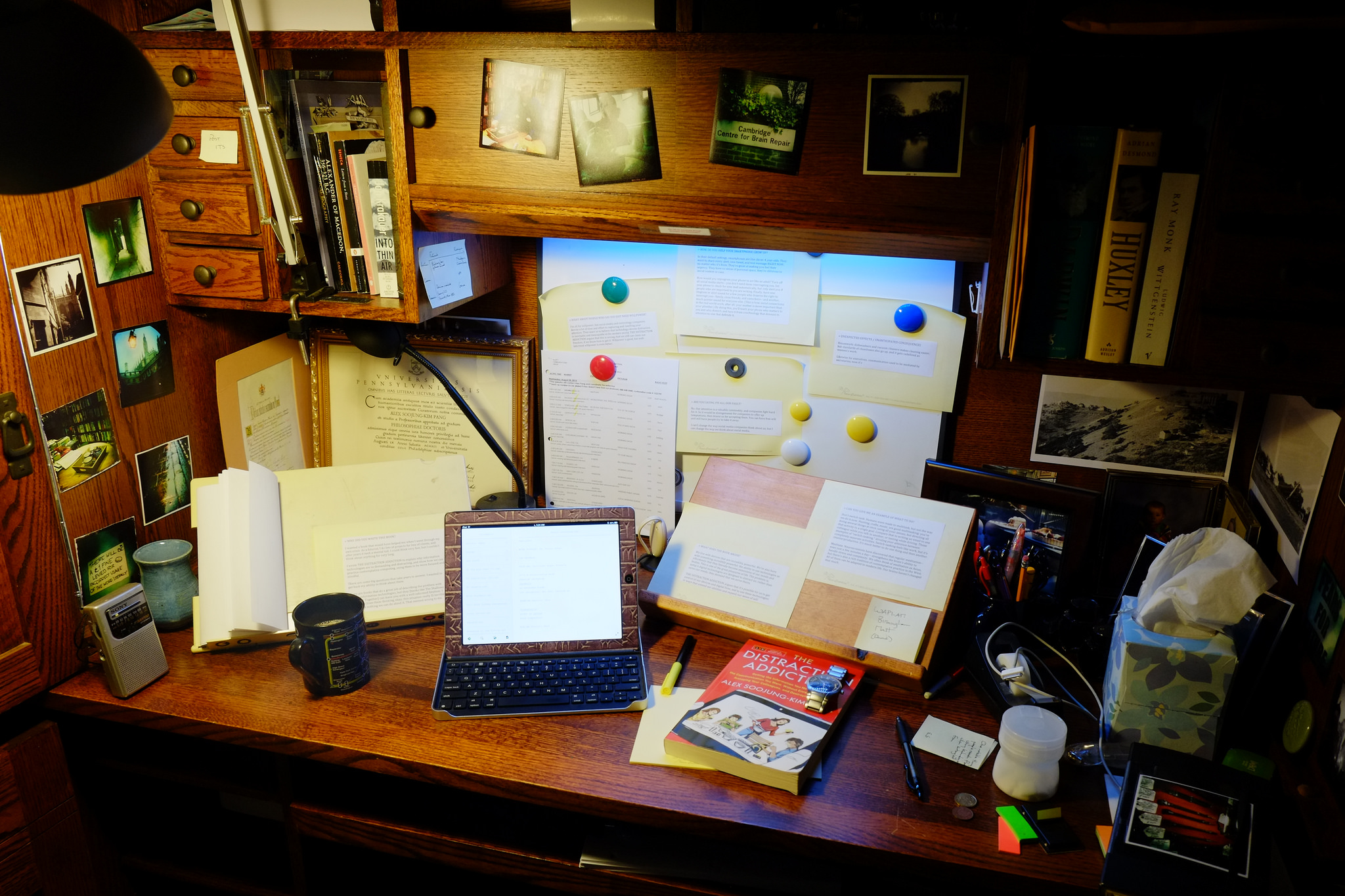

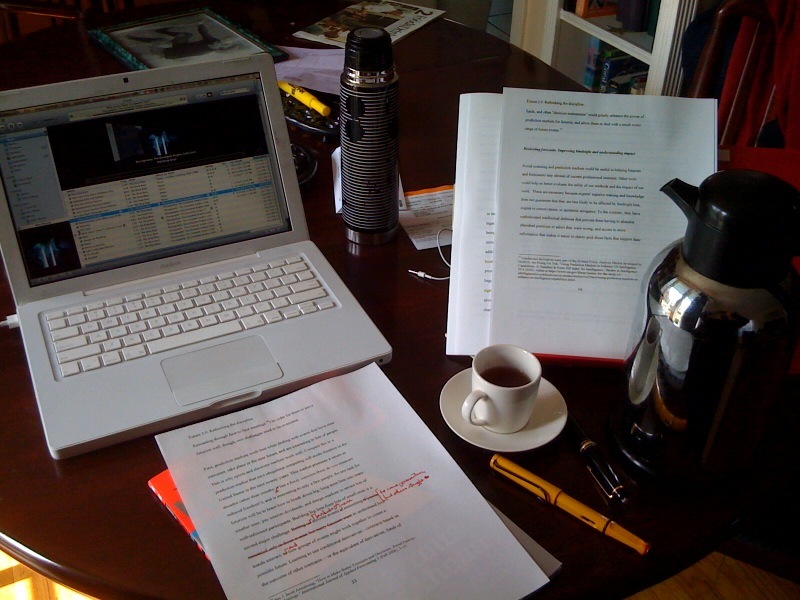

When I was writing my books The Distraction Addiction and Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, I discovered that I did some of my best writing in the very early morning. My kids weren’t up yet, I was too tired to self-distract with social media, and in the pre-dawn hours even my dogs weren’t ready to face the day. On the best mornings, I was creative in a way I wasn’t at any other time. I could write something before I was fully aware of it: I could look at the screen and wonder, Where did that come from?

For a writer, those moments when it feels like it’s not even you writing any longer, that your creative subconscious has free access to your keyboard, are absolute gold. You live for those moments. They can happen any time, but it was clear that in the early hours these periods lasted longer, and the ideas flowed more freely.

There was just one problem: I hate mornings. I’m one of nature’s true night owls. In college I was one of those people who started writing term papers when more sensible people were going to bed.

So while I don’t like getting up before dawn, I realized that if I was going to finish my book, I was going to have to learn how to make early mornings work. What I discovered is this:

My best mornings start the night before.

First, I set up absolutely everything I can: I program the coffeepot, lay out clothes, choose the next morning’s playlist, and even get breakfast together.

The more I arrange in advance, the smoother and more routine I can make things, the more I can just operate on automatic until I sit down and start writing. I don’t have to make any decisions in the morning, and I don’t have any excuses for not getting up.

Second, before I shut down everything for the night, I spend a little time thinking about what I should work on the next morning. I’ll even make a short list of the first things to work on when I sit down at the keyboard the next morning. Overnight, my subconscious will work on the topic, and by the time I get up, it’ll be ready to go. (John Cleese talks about having similar experiences.)

Third, I stop the day’s writing in mid-sentence. This is something that everyone from Ernest Hemingway to Stephen King to John Le Carré to Scott Adams does. It’s a lot easier to start in the morning if your first task is to finish a sentence, rather than confront the terror of a blank page. And leaving that unfinished thought tempts your subconscious to keep working on the sentence– and the next paragraph– while you do other things.

As I explain in a new ebook on morning routines, there’s plenty of psychological research that tells why each of these practices works. This isn’t to say that everyone should adopt them. My practices are designed to support a very specific kind of intellectual labor, and a particular mental state that allows me to do that labor really well. I’m trying to maintain an unstable but powerful blend of blurriness, which allows me to make the creative leaps and new associations that are necessary for good ideas, and crystal-clear focus, which allows me to capture them on the page.

For me, being able to collaborate with my Muse, to have a routine that gives inspiration space to occur, is a critical, even career-defining, skill. If your best work requires different things, your morning routine ought to be different. But if you know what your most important work is, are self-aware enough to know what kind of mental state you need to be in to do it, and are willing to experiment, you can figure out your own ideal routine. It’s worth it. Even if it means having to set the alarm clock for an unpleasantly early hour.