The central theme of my book The End of Old Age: Living a Longer, More Purposeful Life is that the aging process helps us to grow and develop several key strengths, including wisdom, purpose and creativity. The following excerpt from the book focuses on the persistence, growth and importance of creativity in late life, as seen through the seemingly failing life of an aging artist:

It was the winter of 1941, and a 71-year-old man was heading into a disastrous old age. Incessant bouts of severe abdominal pain forced a risky surgery that left him languishing in bed and delirious for months on end. He defied initial predictions of death, but was left wheelchair bound and unable to work in his usual manner. German troops overran his beloved France, tearing asunder the multicolored pieces of his world and sending them to destruction or exile. As the war years advanced, recurrent infections, pain and anorexia ravaged his body. He was bereft of family since his wife left him years before and his daughter was later arrested and tortured nearly to death by the Gestapo. Old age seemed a betrayal of everything he held sacred, leaving him physically disabled and decrepit, isolated and uncertain of his future. A review of his life in those years could easily lead one to cast being “old” as a curse, a dreaded decline, or a tragic gathering in and then a passing on.

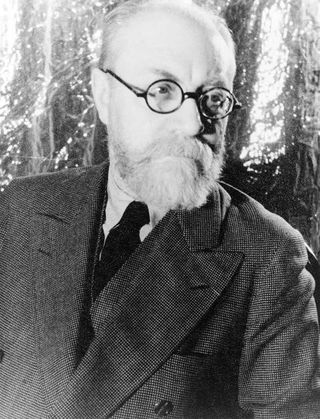

Advance the clock now to the autumn of 2014, when the Paris fashion runways were bursting with color. Models adorned with vibrantly-hued material cutouts pieced into the latest designs of Christian Dior sashayed to thumping techno music and the cheers and calls of the audience. This brash and stylish couture left critics swooning, and was directly inspired, it must be noted, by one withered old man who had been lying half-dead in a hospital bed some 73 years earlier. Something remarkable had emerged from the fading old age of the man in question that continues to have profound influence on modern art, fashion, advertising and culture. It came from the aged life of an individual who had once been written off as half-dead, with his old age imagined as the beginning of the end. In the life of our protagonist, however, who I now reveal as the famed French artist Henri Matisse, we shall see how the maligned oldness ended and age became a dominant strength.

So how did Matisse do it? How did he return from delirium and near death and manage to revolutionize the art world? The nuns who nursed him back to health in the Spring of 1941 called Matisse “le résuscité”—the man who rose from the dead. His survival was unexpected and his recuperation was long and tortuous. He spent most of his time either bedbound or in a wheelchair and was unable to stand and stretch his body to paint on large canvases as before. The man who emerged, however, was clear-minded and determined to move forward: “It’s like being given a second life,” Matisse wrote to his son Pierre, “which unfortunately can’t be a long one.” As he lay in bed during those long months, Matisse might have been inspired by a profound memory from his youth. At the age of twenty, he was similarly confined to bed for many months as he recuperated from an intestinal ailment. Inspired by his roommate and enabled by a gift of brushes, paints and canvas from his mother, Matisse first began to paint, and it sparked a lifelong passion: “From the moment I held the box of colours in my hand, I knew this was my life,” Matisse wrote, describing himself “Like an animal that plunges headlong towards what it loves, I dived in” and discovered a “Paradise Found in which I was completely free, alone, at peace.”

Even in the midst of debility and pain, the aged Matisse was able to return to his art with several commissioned projects, buoyed by a rich correspondence with friends. He started slowly, drawing on the wall next to his bed and illuminating letters and postcards to friends. These writings, full of “boisterous jokes, gossips and ragging” made him feel connected with others and “papers over the cracks of old age—infirmities, ailments, setbacks, loneliness, despondency, fear.” Matisse also developed a genius way to “paint” as never before. His devoted assistant Lydia Delectorskaya would bring vividly colored sheets of paper to the great artist and he would glide a pair of scissors through them, cutting out free-flowing, undulating shapes or “decorations” as he called them, evocative of appendages, flowers, and ferns. He would then direct his assistant to pin them up in various designs on large colored canvases or on the walls. The results were stunning, with their glowing, luminous colors reminiscent of the beautiful and refined fabrics woven by his ancestors in northern France, and their shapes celebrating the freedom of movement and spirit in post-war Europe. Matisse’s new style of paper cut-outs first appeared in a book called “Jazz” published in 1947, and consisted of a menagerie of acrobats, circus performers and animals all rendered in bold cut-outs. Perhaps the most famous image is Matisse’s rendering of the mythical Icarus with his bulbous black body and brilliant red rounded heart splayed against a dark blue sky and lit up by several yellow starbursts. The image is equally symbolic of an aging Matisse, perhaps plunging towards earth and dying, or maybe simply reclining peacefully against an illuminated sky, his heart still beating furiously.

There are two magnificent elements to Matisse’s resurrection that speak to the power of aging. First, his cut-outs were simultaneously an expression of continuity from his entire past body of work, while also a radical new approach to art. Second, there was a spirit of boldness and freedom in his works that made them so compelling compared to anything that had come before. Matisse was clear that the secret force that enabled this departure was aging: “Even if I could have done, when I was young, what I am doing now—I wouldn’t have dared.” Age brought him courage and enhanced his creativity. His final masterpiece, created shortly before his death in 1952, was a completely designed chapel in Vence, France, dedicated to the nurse turned nun who cared for him after his surgery. The sublime shapes and colors of the stained-glass windows reflect the essential gift of aging that Matisse articulated so well: “I have needed all that time to reach the stage where I can say what I want to say.” This is a powerful statement that every aging person should be able to embrace.

We learn from Matisse and many others an essential lesson of creative aging: the process of renewal can be life-affirming and life-saving. It involves reaching out to the best from our past to recapitulate parts of it, revise other parts, and re-do them—but in a new context. Matisse himself described how his past helped in the creation of the Vence chapel: “It is the whole of me,” he wrote, “everything that was best in me as a child.” He preserved the essential memories and ideas from his past but recast them into something new. We may fear change and the unknown of aging, but renewal reassures us and bolsters us with our memories and wisdom, even as it demands that we rework them.

Excerpted from The End of Old Age: Living a Longer, More Purposeful Life by Marc Agronin, MD. Copyright ©2018. Available from Da Capo Lifelong Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Originally published at www.psychologytoday.com