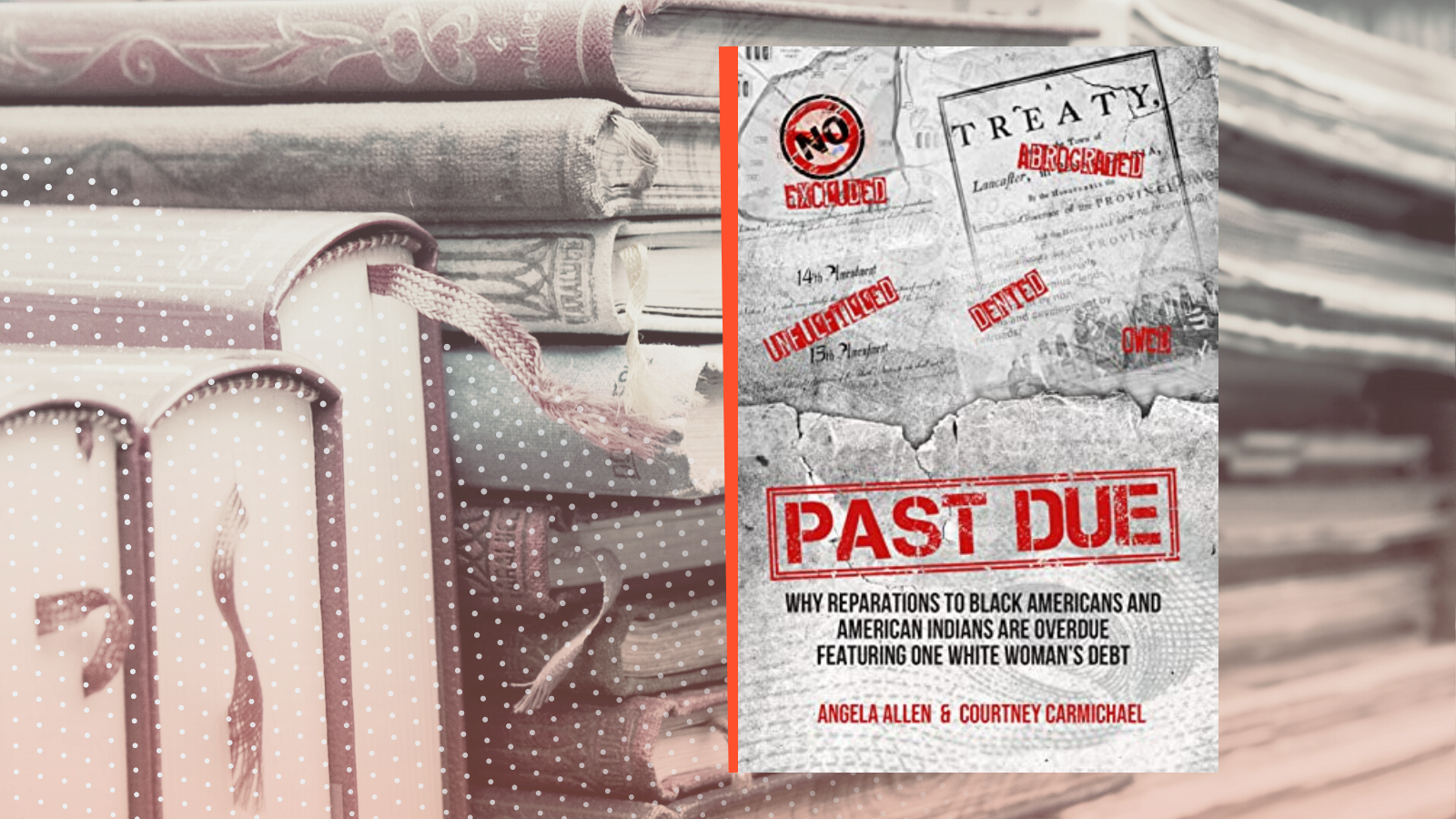

The idea that there is one Black History Month (February) or one International Women’s Day (March 8th) or one Indigenous People’s Day (the second Monday in October) is a limited frame for sure, and many argue that these special “celebrations” give way to a continued lack of attention or interest in the history for the rest of the year. No doubt that is true, and I am writing this week about Black Americans not because it’s Black History Month, but because I have recently read an important new book titled Past Due: Why Reparations to Black Americans and American Indians Are Overdue: Featuring One White Woman’s Debt. You can download it for free on Amazon — it’s free because the intention is to educate, inform and ignite conversations and action.

“Reparations is a charged idea that was not even on my radar screen,” says co-author Angie Allen. “But once I started a deep dive into the history of the attempted genocide of American Indians and the confiscation of their land, and the atrocities committed against formerly enslaved Black Americans, I found irrefutable evidence that I – as a White person – had unfairly benefited at the expense of these groups of fellow human beings.”

In this diligently researched book, there are two voices — Angie Allen, a 70-something White Northern female and Courtney Carmichael, a 30-something Black Southern female. Together, Angie says, we created “what we hope is a useful, reference- and resource-filled manual for White Americans who want to learn more and pursue their own ‘re-redistribution’ of White privilege.”

A former investment banker, Angie began cataloging all of the benefits, privileges and opportunities that have come her way as a White person in an arbitrarily structured, falsely-based societal hierarchy.

She writes, “I realized that I have been complicit, and I began to map out a plan to rectify my own role in systems that continue to favor White Americans, a roadmap to put it right, at least in my own situation. I don’t call it reparations. I consider it to be re-redistribution.”

Whatever term is used to describe the need to repair the harm done to Black Americans and American Indian communities and to offer some form of redress, making reparations is not a new idea. The first call for reparations came more than a century ago…and from Black women leaders!

“Black women have created, led, and sustained the reparations movement for more than a hundred years,” writes Ashley Farmer this week in the Women’s Media Center blog. “Their efforts laid the groundwork for the increasing number of reparations bills, programs, and restitution funds of today.”

The mothers of the movement, Callie House and Audley Moore, “worked tirelessly petitioning the government for support for Black Americans” asserting “that Black people were due repayment not just for their unpaid slave labor but also for the systematic destruction of their culture, identity, and wealth, as well as the government’s denial of their constitutional rights under Jim Crow.”

Both of these women, Farmer notes, labored “on the margins for years, called crazy and unrealistic by those around them.” It wasn’t until 1989 that Rep. John Conyers introduced HR 40, which would establish a federal commission to study the history and “recommend appropriate remedies.” The 40 number refers to “the unfulfilled promise” the United States “made to freed slaves: that after the Civil War, they would get 40 acres and a mule.”

For three decades, Conyers continued to introduce HR 40 each and every year, without any forward movement. In 2021, the bill was introduced again by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee and, for the first time, voted out of committee for consideration by the full House, and that’s the status today, more than a century since the first proposals were put forward.

But it’s important to note, as co-author Courtney Carmichael points out in her introduction to Past Due, “this bill is solely focused on Black Americans. There isn’t another bill out there to address what is owed American Indians, who have suffered at the hands of the government. …Reparations are needed for Black Americans and American Indians.” Some of you may have seen the 60 Minutes piece on Canada’s “cultural genocide” on indigenous children this past weekend, which I encourage to watch if you haven’t. It’s important to note that Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland has opened an investigation into American Indian boarding schools, and I’ll be writing more about that in coming weeks.

The current debate over teaching America’s racist history makes Past Due a timely book. As Angie says, “We have sharply divided views in America on racism at this very moment. Recent books, articles, podcasts, TV shows, and movies are shining a bright spotlight on our racist past and present. At the same time, societal upheaval indicates that there are also growing racial divides. This divisiveness means that this handbook, targeted at people classified as White in America, will likely appeal to some and not others.”

Past Due doesn’t lay out a roadmap for mass reparations or re-redistribution, and it’s important to recognize that there are currently efforts underway to shape ways to do both. Last year, Evanston, Illinois, became the first US city to pay reparations to Black residents, funding the payments through donations and revenues from a 3% tax on the sale of recreational marijuana. That effort was led by Alderman Robin Rue Simmons, who is also the founder and executive director of FirstRepair, a new not-for-profit organization that informs local reparations nationally. The city has pledged to distribute $10 million over 10 years. It’s a bold plan which hundreds of other cities and communities are watching closely as they consider their own reparations as a way to repair the harms of the past.

In Past Due, Angie and Courtney emphasize the importance of White people doing the work. For all of us, the work to repair, heal, and find sustainable means for reparations or re-redistribution must be intentional and deep, and it begins with being better informed.

“A guiding light for me in writing this book was to be both honest and upfront about the regrettable fact that it has taken me so long to begin examining my own White privilege,” writes Angie in the Preface. “I wish this true history and state of conditions would be incorporated into all American school textbooks. I wish I had learned it from the start.”

Learning this history and connecting it to the reckonings of the present should be a part of every American’s education, but currently there are organized groups in many states trying to prevent it. The profusion of education bills being introduced and passed across this country – legislation that censors history and seeks to restrict what students learn about America’s past by banning books and silencing teachers — makes the self-education that Angie and Courtney took upon themselves and share in this book all the more critical.

Knowing the history, as both authors of Past Due point out, is an important starting place for a journey of learning and acting in good faith. I am on this journey to learn and join the efforts to repair the harms of the past, a necessary step towards fulfilling the promise in the Pledge of Allegiance — “with liberty and justice for all.”

That is a promise past due.