“The most serious blow suffered by the colonized is being removed from history and from the community. Colonization usurps any free role in either war or peace, every decision contributing to his destiny and that of the world, and all cultural and social responsibility.”

— Albert Memmi, The Colonizer and the Colonized

To give credit where it’s due, the coronavirus accomplished something neither Carrie Lam’s government nor her Beijing overlords were capable of doing: return peace to the streets of Hong Kong after more than seven months of social unrest.

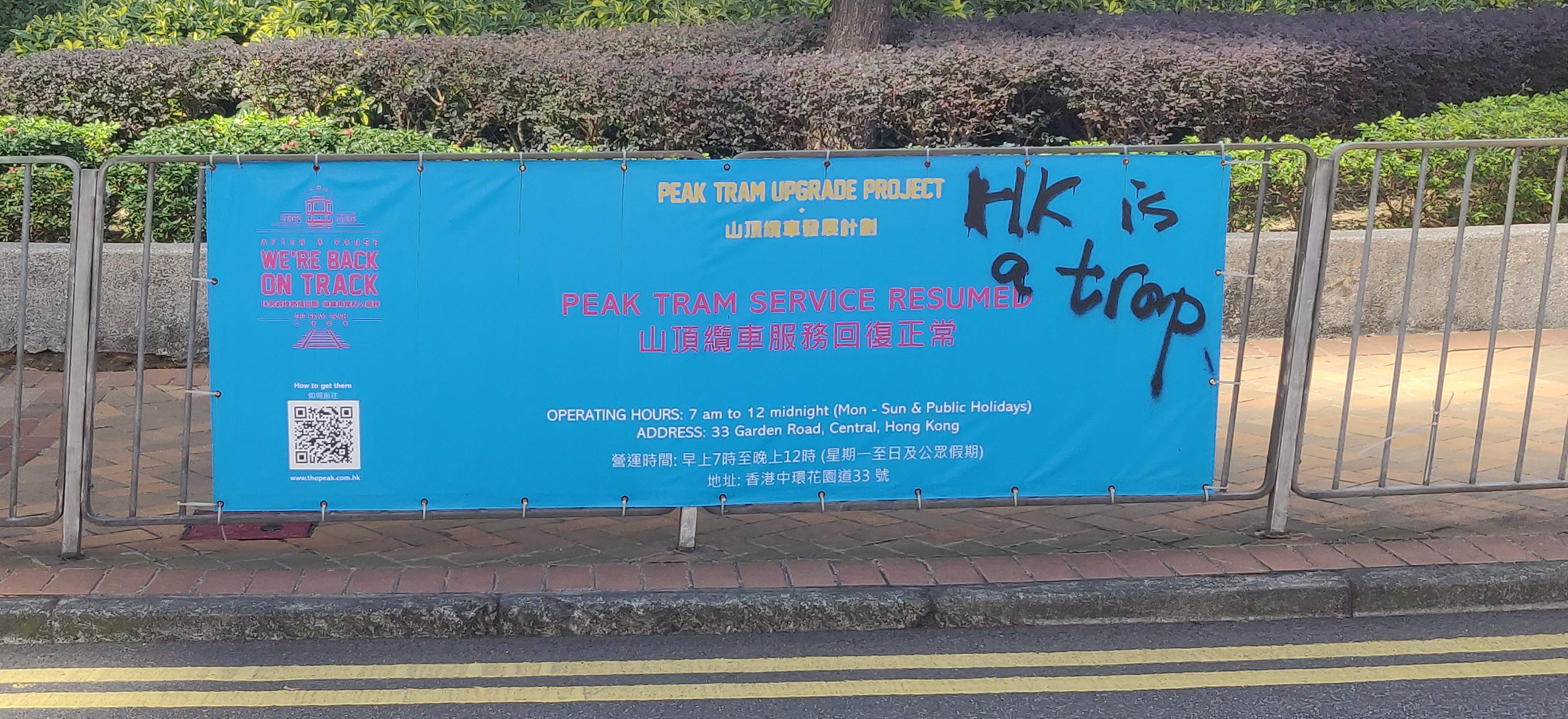

While the firebombs and vandalism against the police and corporate Chinese interests waned—and the city’s mask ban largely abandoned as the entire populace covered up against the virus—anxiety permeates the city; a collective dread far murkier than the low clouds of a cool, damp winter.

The city, known for its kinetic energy—as if “someone had kicked an anthill” observed a friend—is now moribund. The revelry of such notorious neighborhoods as Lockhart Road in Wan Chai and Lan Kwai Fong in Central—excessive drinking, prostitution, drug use—are somber most evenings. Tourism plummeted an unfathomable 99% between February 2019 and February 2020, from 200,000 visitors per day from China and elsewhere to a little more than 3000, Bloomberg News reported.

The city’s economy continues to decline, and people — ex-pats, young native Hong Kong professionals, Chinese nationals — are leaving. In a recent poll, more than 40% surveyed wanted to leave the city “citing factors such as ‘political disputes’ and ‘lack of democracy’.”

A friend in C-suite recruitment, who spent more than 20 years in Hong Kong, told me of two candidates, finalists for a major role with a global recruiting firm, who withdrew their candidacies. Both were professionals with more than a dozen years of combined experience in the APAC region. “They’re afraid,” he shrugged. “There is too much uncertainty.”

Former colleagues at two of the city’s largest restaurant groups—an industry already reeling from protest disruption—reported a drop in customers in January by anywhere from 50 percent to 75 percent, with some owners taking desperate measures to ride out the storm. “I was told I had to wash dishes,” a young marketing employee of one of the groups told me. “So, I quit.”

An acquaintance who works at Hong Kong’s iconic Peninsula Hotel on the harborfront of Tsim Sha Tsui confided in a mutual friend that over the St. Valentine’s Day weekend there were only a total of six bookings. In a hotel with 300 rooms.

The Political Theater

The coronavirus has brought anxious peace to the city. But the anxiety unseen on the streets is felt in the boardrooms of the city’s corporations. As 2019 ended, Hong Kong slipped into its first recession in a decade. As the virus cleared the streets, multinationals began work on contingency plans, exit strategies, pricing office rental properties in Singapore and Samoa.

By December, as Hong Kong entered its seventh month of protest, Western media remained committed to the “David v Goliath” narrative; the valiant freedom fighters on the streets of Hong Kong rising up against the stifling hegemonic power of the Communist Party in Beijing.

And what was not to love?

Protesters had an endearing public face in the pro-colonial Grandma Wong, the British flag-waving senior who “misses the colonial times”; a Canto-pop anthem for the ages, “Glory to Hong Kong”, and striking ready-for-prime-time visuals of black-clad rebels wielding light saber-like green lasers for the TV crews at night as bonfires burned in the streets. (“It’s so Hollywood,” laughed one longtime Hong Kong journalist.)

The visuals may be cinematic, but the media consumed in the west largely fails to put what’s happening to Hong Kong into an accurate historical context. At the height of its imperial power, the United Kingdom established Hong Kong as a trading post to quite literally sell opium to the masses.

Following the First Opium War (1839 to 1842), the formal British colony* was established around 1842 and Hong Kong became home to Chinese political dissidents fleeing the Manchurian government, as well as pirates, drug dealers, and criminals. A Second Opium War took place between 1856 and 1860 when the British, with allies the French, completed the work of the first war, weakening the Qing Emperor’s rule, and legalizing the opium trade, creating generations of drug-addicted Chinese.

Images of Hong Kong, for better or worse, remain for Westerners a stereotypical hodge-podge of colonial romanticism—the cosmopolitan international finance hub, a neon and LED-lit warren of exotic pleasures, or a shining beacon of liberty in that smothering cauldron of Godless Communism, the People’s Republic of China.

“We’re in a new Cold War,” screamed an OpEd piece in USAToday, and “Hong Kong, like Berlin before it, is the first battle.”

“The United States must not turn a blind eye to the violations against Hong Kong’s freedoms and autonomy,” warned an ominous Newt Gingrich in a column for Newsweek.

By my reckoning, the most distorted lenses were worn by New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff, who spent decades chronicling the underdogs of globalization. His columns and social media posts from his visit to Hong Kong in August offered little insight into what actually tipped Hong Kongers into peaceful, then violent protests beyond the handy “Hong Kong, good. Beijing, bad” trope. In one article, he accused China’s President Xi Jinping of tarnishing “the word ‘Chinese.’”

“Hong Kong has been colonized not once but twice.”

Yet, everything about these analogies is wrong. Whether the West likes it or not, what’s happening in Hong Kong is a domestic Chinese issue.

Furthermore, it is also a class issue, where a small number of obscenely wealthy Hong Kong developers have for now more than a century controlled property, and more importantly, its availability and how the land can be used, leaving not one, but almost three generations of native Hong Kong Chinese struggling for both homes and opportunity.

Hong Kong has been colonized not once but twice.

First by the British which gave the city its romanticized global identity as the glittering island of free markets and free speech, a discomfiting pebble in the heel of Red China; and the second time, by Beijing — which while it has yet to send its troops — did send its millionaires and billionaires into the post-handover world who bought up all the property, set up tax-sheltered companies and imposed “Mandarin-speakers preferred” hiring rules throughout the city’s corporate culture. (“Twenty years ago if you spoke Mandarin you wouldn’t be allowed into the Louis Vuitton in the Landmark Building,” remarked one British lawyer. “Now you have to speak Mandarin to work there.”)

Western media’s need to paint the Hong Kong protests in simplistic, Manichean terms does two things; first, it lets the West, particularly the British off the hook regarding its history of colonialism, and second, it propagates the ongoing ignorance in the West of Chinese governance, that the country’s brutal authoritarianism is rivaled only by the country’s economic success and its cultural sophistication.

This is not a blanket defense of China and its ruling political body, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But, to say that China is “communist” at this point is laughable on its face. China has a robust socialist market economy ruled by an authoritarian, one-party regime. Do not conflate the two.

“What’s the underlying problem in Hong Kong?” a retired expatriate police officer asked recently. “I don’t think it’s the extradition bill. You look at some of the places the people are asked to live then maybe you see that they have nothing to lose. The job situation is dismal and there doesn’t seem to be anything from the government that says, ‘we’re looking out for the welfare of the citizens’.”

There is a fear in Hong Kong that once the coronavirus crisis has passed, the protests will renew, with fewer participants, said one local journalist, a videographer and documentarian, but far more violent. Just as the virus struck, some of the angrier protesters had begun experimenting with IEDs, planting firebombs in hospitals.

“These protesters, they’re just desperate,” said the retired ex-pat police officer. “They’re angry and they see no future for themselves.”

Over the course of the protests, the tenor of the demonstrations evolved, from the peaceful student protesters to garnering support amongst the professional classes—lawyers, doctors, and educators—who often showed their support by holding spontaneous peaceful demonstrations that stopped the city in its tracks.

“Hong Kong has one of the widest gaps between rich and poor in the world.”

But over time, that too changed. The money and external support of the movement, as misshapen and vague as it’s been at times, began to reflect those external powers with a vested interest in keeping Hong Kong on edge and Beijing off-balance.

A survey of the reporters, academics, and law enforcement I spoke with over the last few months agree that from the beginning, the protests were well funded, everything from bottles of water to toothbrushes to packed lunches, masks, and placards, often handed out from public restrooms in shopping malls and public parks or from the backs of trucks and cars.

Yet the recent arrest of four members of the Spark Alliance, an online crowd-sourced funding platform, offered insight into the money behind the “grassroots” movement.

The usual suspects are, of course, the United States government, as well as pro-democracy Hong Kong ex-pats in the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK. But over time, money began to trickle in from China, as some “Mainland Millionaires”—purged from the Chinese Communist Party due to a “corruption” clampdown—saw financially supporting the protests as a way to give President Xi Jinping a black eye.

The videographer recalls a recent conversation with a landlord who watched a construction crew on a project next to her building wrap up for the day, then, armed with masks and 500 RMB in their pockets begin their shifts on the front lines of the protests. “We went from skinny college students at the beginning of the protests,” he said, “to these big guys, construction guys, paid for their time.”

In the early days of the protests, I received emails and instant messages from friends and colleagues after I posted a personal note detailing our experiences here Hong Kong and our feelings of relative safety:

“Is this the beginning of a civil war?” one asked. “Have the protests spread to other cities?” questioned another; and my favorite: “Whatever you do, don’t go to China. They might detain you.” A recent trip to Shanghai was pleasant and decidedly uneventful, but thanks for your concern.

The West’s understanding of modern China—of post-colonial Hong Kong—and indeed the overall emergence of Asia as a sociopolitical and economic force is still viewed through those prisms of Western Ascendancy; first, European imperialism and second, post-WWII Cold War elitism: Hong Kong is idealized. “Hong Kong isn’t like the rest of China. Hong Kong is the role model that the rest of China should follow.”

At least, that was the initial premise when both China and the United Kingdom agreed upon the Basic Law to govern Hong Kong following the handover in 1997.

“It seems to me that the 50 year time table was always predicated on the assumption that mainland China would democratize,” Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University told me in an interview. “By 2047 it was assumed that the 50 years would have provided an adequate cushion of time for the People’s Republic of China to evolve towards Hong Kong’s liberal values.”

It’s as much a commentary on Western arrogance as it is on Chinese intransigence, to say that reports of this miraculous political and social transformation have been greatly exaggerated.

Chinese Democracy

The anger is now no longer about the extradition bill,” explained Prof. Ma Ngok, a political science professor with the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the author of Political Development in Hong Kong. “The original bill is dead.”

But, just as the protests themselves had heaved and expanded through the city, branching out from designated routes, into peripheral alleys and lanes, from subway stations and malls to the airport, so, too, did the demands. “Now the focus is on police brutality,” Prof. Ma said. “But the overall grievances are based on the fear of losing a way of life.”

While ostensibly protesting for democracy, the West fails to remember—or realize—is that even under the British, traditional democracy was denied the local Chinese well until the 1980s. And not until the 1990s, just before the Handover and the establishment of the “One Country, Two System” model for China and Hong Kong the last British Governor, Chris Patten, decided as a parting shot, to unilaterally democratize Hong Kong, angering Beijing and in many ways setting up the scenario for not just the recent demonstrations, but also the Umbrella Movement of 2014.

“Hong Kong has never been a democracy,” Prof Ma told me. “Hong Kong has relative personal freedoms compared to China and other countries in the region, but it has never been a democracy. Most of how the West viewed Hong Kong under the British is simplified, but even the political freedoms and rule of law—especially in the 1970s—were overstated. The civil service and the police were very corrupt.”

The former Hong Kong police officer, who arrived nearly a decade before the Handover, tells the story of investigating the death of an elderly Chinese woman in the city’s Wan Chai neighborhood one Saturday night in the late-1980s. The officer in charge, also a Brit ex-pat, upon seeing the victim, head bludgeoned in by a hammer, the murder weapon left on a night table, declared the incident a “suicide” in order to wrap up the case and get back to his drinking. “He just couldn’t be bothered,” the retired officer recalled.

Hong Kong, it would appear, has more democracy now under the Chinese than it ever had under the British.

Identity Crisis

In 1957, the Tunisian-born French writer and philosopher, Albert Memmi, published his seminal work, The Colonizer and the Colonized, about the interdependencies created between the European imperial powers that colonized the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa between the 17th and 19th centuries and the peoples that they subjugated.

Originally published in French, the book quickly became a touchstone of the freedom movements of North Africa, Vietnam and beyond, gaining such notoriety that if found in the possession of imprisoned rebels and insurgents, it was quickly removed, its owners punished.

Translated into English in 1965, the book went on to influence a generation of African-American and Chicano civil rights protesters in the United States, as well as revolutionaries throughout South America and Southeast Asia.

It is a slim tome, but dense in its dissection of what colonialists bring to the worlds they invade, what they take away from the indigenous people, and the ruin they leave in their wake.

While having gone out of vogue in contemporary progressive circles, Memmi’s message about the wages of colonialism is as resonant today in Hong Kong as they were more than 50 years ago when the post-War world was being redefined by the Cold War; when the United States and the then-Soviet Union rushed in to gather up the pieces of the collapsing empires of Europe.

Longtime journalist and Hong Kong resident, Mark O’Neill has a far more blunt appraisal: “If the (Hong Kong Chinese) had been offered the choice of another 50 years of British rule or a return to China, most would have voted for another 50 years of British rule.”

O’Neill, an Irish native, arrived in Hong Kong in 1978 and has lived in Asia ever since, spending time in China, India, Taiwan, and Japan. Animated, lean, with a sharp nose, ruddy face and expressive eyebrows, he hunched over our table at the Starbucks in Lan Kwai Fong in Central, punctuating his points by jabbing a finger at the Cantonese headlines in the wad of local newspapers he’d strewn across the tabletop.

We met in late-October, just as the violence had begun to veer out of control before culminating in the 13-day siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University that turned the campus into a battlefield.

A journalist for more than 30 years—including a stint with Reuters for 13—since 2006, O’Neill has been writing books on Chinese, Hong Kong, and Macau history and society. His two most recent ones are Israel and China: from the Tang Dynasty to Silicon Wadi and How the South Asians Helped to Make Hong Kong.

For many Hong Kong Chinese, for those who fled their homes in greater China because of the Communists at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950, and those who arrived later, following the purges of the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976, fear and distrust of Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party is very real, O’Neill told me. This resistance is the core of what it means to be from Hong Kong.

“The Chinese who came here made the right choice because the conditions at home were so dangerous,” O’Neill said. “Under Communist rule, millions of people were killed. The Chinese who escaped here, their mindset is different, unlike other colonials they never called for independence; they have a much more favorable view of the British.”

“Old people can’t retire, there are old women out collecting cardboard and men in their 70s driving buses.”

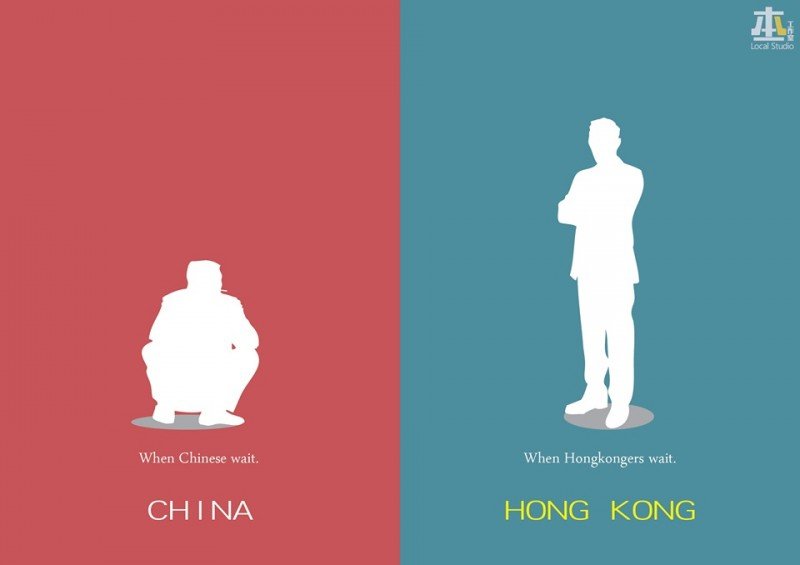

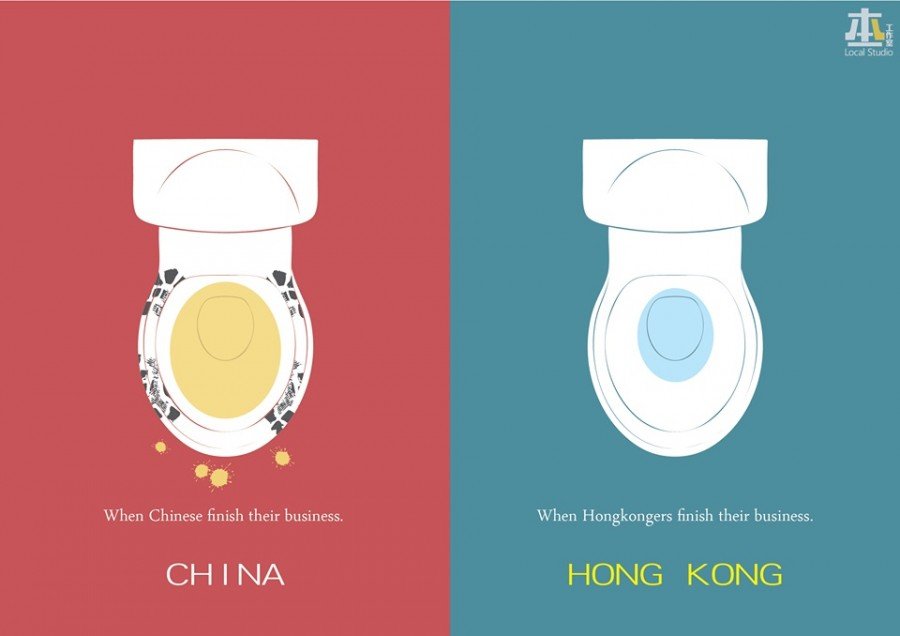

It’s the issue of cultural identity, of a kind of cultural superiority, that underpins some native Hong Kongers resistance to not just accepting that Hong Kong is a Chinese city, but actually embracing China’s economic and technological successes over the last 30 years or so.

“It used to be Hong Kong was the rich cousins and China was the poor cousins,” said the ex-pat cop. “But a lot of Hong Kong Chinese don’t like the fact that China has become wealthy. I mean look at next door, (Shenzhen) was nothing more than a fishing village 20, 30 years ago.”

“I’ve spoken with these protesters,” the officer told me, “and they can’t tell you what it is they’re really angry about. It was the same during the Umbrella protests (in 2014). Many of them don’t see becoming part of China as an opportunity.”

Having been in Hong Kong for more than 25 years the officer who had native Hong Kong Chinese officers under his command believes that blaming Beijing is just an excuse.

“(Hong Kong has) one of the widest gaps between rich and poor in the world. Old people can’t retire, there are old women out collecting cardboard and men in their 70s driving buses,” the officer said, ruefully. “For a government that’s got so much money you can’t understand why they can’t supply a social support platform.”

Of this, “Grandma Wong” is possibly the best example of Hong Kong’s failure to provide for its people. Forced out of Sham Shui Po, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods due to the neighborhood’s rising rents, Alexandra Wong, moved to the neighboring city of Shenzhen—the “Mainland”—almost 14 years ago in order to have a home. “I don’t like to live there, of course,” Wong, 63, told Reuters. “It makes me sad all the time, but I cannot live in Hong Kong.”

The protesters are demonstrating for democracy. But all politics is local and there is nothing more local or political — or barely democratic — than Hong Kong’s property laws and property developers.

If the protesters are fearful of the loss of a way of life, the freedoms of movement, privacy, and expression left behind by the Brits; on the other side of that coin are the corrupt and brutal realities of property rental and ownership in Hong Kong.

“Only 50% of the residents of Hong Kong own their own roof,” a longtime journalist told me. “The other 50% have to pay exorbitant rents on tiny apartments or live in slumlike conditions with multiple beds in a room, nonstop noise and a lack of facilities.”

Originally hailing from Malaysia, this journalist has spent more than 35 years in Hong Kong, he married a local woman and the couple has a daughter. His view on the recent events is bemused resignation, an acceptance of a dreaded inevitability.

“The thing that sticks out for me is that since 1997 is that Hong Kong has had zero leadership,” he explained to me over coffee at a co-working space in Wong Chuk Hang. “We’ve gone through two decades-plus on autopilot, no one on the bridge, no one scanning the horizon. No one saying, “Is this what we should do to address?” What are the core issues of Hong Kong? And at the heart of everything that’s wrong with the city-state is unaffordable housing.”

The Simmering Resentment

“It is significant that racism is part of colonialism throughout the world, and it is no coincidence. Racism sums up and symbolizes the fundamental relation which unites colonialist and colonized.”

― Albert Memmi, The Colonizer and the Colonized

On a recent sunny, Saturday afternoon I met up with “Charles”, a 28-year-old marketing professional at another Starbucks, this one in the Sheung Wan neighborhood. (The only Western chain more ubiquitous than Starbucks in Hong Kong is 7–Eleven. Seriously, they’re everywhere.)

The air is cool and humid, one of those oddly uncomfortable sub-tropical winter days when wearing shorts and a t-shirt makes sense until the sun sets, a cool, damp breeze rises and putting on a sweater or sweatshirt just makes you perspire.

Like his contemporaries worldwide, Charles has his head buried in a multi-player mobile phone game while nursing a grande latte when I arrived; oblivious to my presence until I plopped my laptop down next to him on the table.

“Sorry!” he apologized with a broad, embarrassed smile as he removed his headphones and turned down his phone. Tall and wiry, with a painfully narrow waist, and coathanger shoulders, he stands a good 6’3″ to 6’4″ tall with an easy gait and infectious smile.

Charles is from Shenzhen. Born and raised. As well as English, he speaks Mandarin, his native Cantonese and the local dialect of his people, the Hakka. “The ‘natives’,” he joked.

He first came to Hong Kong to study in 2014 and remembers vividly the Umbrella Movement and watching his fellow students skip classes to participate; something he acknowledges would never happen in his hometown, or in nearby Guangzhou or any other city in greater China.

“When I first came to Hong Kong, I set up a Facebook account,” Charles recalled. “I then signed up for all these local Hong Kong (newspapers) that we can’t get in Shenzhen.”

At first, he was impressed with the freedom of expression, the passion, but soon, Charles became disaffected, hurt, and in a small way, afraid.

“After a while, you realize that they (the Hong Kong Chinese) actually kind of hate us,” he said with a nervous laugh and a shrug. It’s clear that despite having lived and worked in Hong Kong for more than six years, he is wary and more than a little disappointed.

The disdain and resentment towards people from the greater China have been constant throughout the demonstrations, with one artist creating a series of 22 illustrations explaining Hong Kongers’ cultural superiority. Speaking to Hong Kong’s Passion Times, the artist said the images “mourn the fact that Hong Kong has been ‘colonized’ by mainland China” and to “tell the world about the differences between Hong Kongers and Chinese people”.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, protests were routine and often spontaneous. Attacks on businesses with connections to Beijing and greater China were many—Starbucks, Bank of China branches, all experienced attacks, with employees and customers being both verbally and physically abused by protesters.

One morning, a protest erupted near Charles’ office, he read about it online and called into work sick. He is only one of four Chinese working in an office made up predominantly of Europeans. That said, being from Shenzhen, he works for a native Hong Kong Chinese manager.

“Even though we are both Chinese, I can’t talk to her or tell her how I feel,” Charles told me. “Because we don’t have that kind of relationship. I don’t know where she is on the protests.”

This fear goes beyond the office. “You can’t speak in public. Or you can’t speak (in Mandarin) in public. My friends call me from Shenzhen, I see their name and number, and, Beep!” he motioned muting his mobile phone and laughed. “Won’t answer that! Will call them later.”

Colonialisms Legacy

Beijing’s handling of the coronavirus crisis is everything Hong Kong—and the West—rightfully fears about China. The lack of transparency, the duplicity, and misinformation, the harassment of the truth-tellers that puts protecting China’s reputation above and beyond the protection of not just its own people, but the world.

The Chinese government is ruthless and efficient as the world witnessed with Tiananmen Square, its routine detainment of democracy activists, the temporary vanishing of errant celebrities and the ongoing suppression of the Uighurs in Xinjiang province.

The Chinese Communist Party is omnipresent and in this digital age, omniscient.

“The Chinese Communist Party is at its core, a Marxist Maoist ideological prison,” said the journalist. “But when it comes to Hong Kong, Beijing is clueless. It is clueless about what made Hong Kong work. It believed that the Hong Kong civil service understood the dynamics of the city following the handover, but that was the big mistake.”

Both the journalist and the retired police officer agree Beijing has always wanted Hong Kong to work; not that the CCP was a fan of the city’s diluted democracy, but because it could use Hong Kong’s success to appeal to Taiwan. That “One Country, Two Systems” would lead to unification between Taiwan and the Mainland.

“Beijing did not begin with the intent to sabotage Hong Kong,” the journalist told me. “If anything they wanted it to succeed with minimal interference.”

But Beijing let Hong Kong’s wealthy developers have too much say, too much power since the handover; and the influx of wealthy Chinese purchasing many of the city’s finer apartments and offices created the crisis, fanned the flames of resentment and powerlessness. “Beijing’s failure of leadership is its failure to reconfigure the power relationships between Hong Kong’s property cartels and the Hong Kong government,” the journalist said.

And the protests grind on…

Just as reports of coronavirus infections in China were abating, demonstrators returned to the Kowloon streets of Mong Kok and Prince Edward on the last Saturday in February. 115 protesters were arrested. The uneasy truce it appears, won’t outlast the virus.

For decades, Hong Kong has been called, “the Pearl of the Orient”. It’s a nickname of particular resonance, not just for its romantic or colonial connotations, but for this definition that I found while researching this essay: “A pearl was precious and therefore Hong Kong was ‘precious’ in the sense that it was under pressure from all sides without having any natural resources of its own.”

It is a beautiful and apt description. In less than 30 years the Basic Law, the handover agreement of “One Country, Two Systems” is scheduled to end. As of today, there is no plan to extend Hong Kong’s status as a Special Administrative Region beyond 2047.

Both the Hong Kong government and Beijing encircle the people of the city-state, asserting pressure that drives property prices higher than the city’s tallest skyscrapers while forcing its citizens out onto the streets in poverty, protest, and frustration.

Charles and I left the Starbucks at 4 p.m. sharp that Saturday; like many Hong Kong businesses, it’s cutting back on opening hours to save money. We walked onto the courtyard of Sheung Wan’s COSCO Tower to bid our farewells. He has no plans to stay in Hong Kong and will decide soon whether to move back to Shenzhen or make the move to Shanghai. “The Chinese seldom unite,” he told me. “But often turn on each other.” A century ago, many Chinese literary figures, like Lu Xun wrote about the Chinese propensity to tear each other down, said Charles.

As I turned to head towards the MTR station, Charles yelled. “As the poet said 100 years ago, “Only the Chinese can fucking hate the Chinese!”

*Between December 25, 1941, and August 30, 1945, British Hong Kong was controlled by the Japanese Empire at the height of World War II