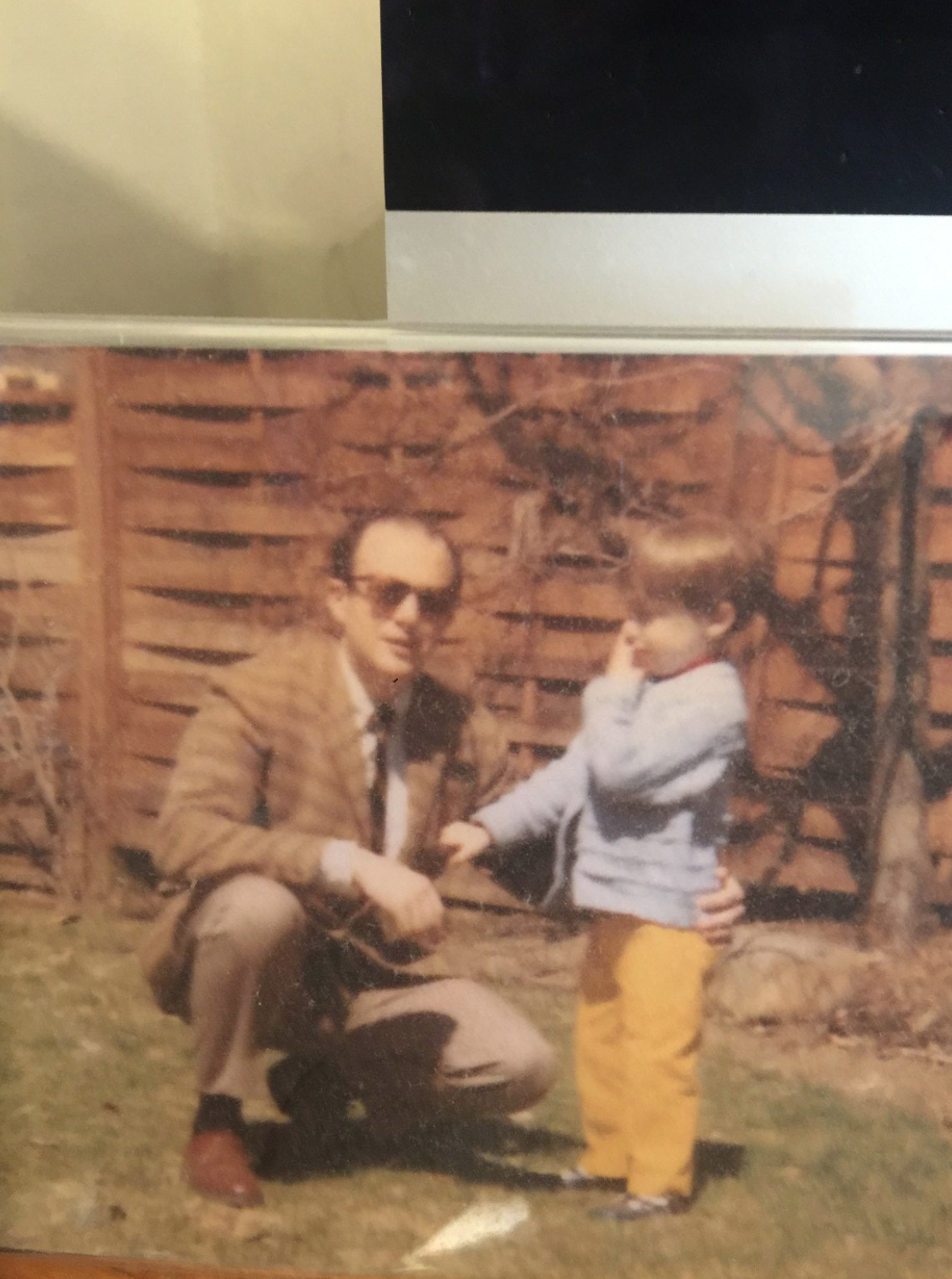

My dad, Bob Jaffee, did not like hearing or using the word, “love.”

That is okay. I still told him that I loved him.

And we all have our flaws.

Even Moses did not get to enter the Promised Land, though he did get to view it from a distance. And King David conceived of building God a temple, even if he did not get to see it completed.

My dad, a mensch of mensches, who passed away on May 15, was not per se a religious man. And he might have been surprised at any comparisons to Old Testament figures.

But my dad was very heroic and spiritually connected in his own way. He believed in facts and the truth, and he lived by a code of ethics, just like the founders of this country, just like the patriarchs from the Bible.

That did not mean that he wanted to talk about religion or current events near the end.

As my dad was fighting metastatic cancer, something he had battled for about five years, I talked to him, in recent days, almost exclusively about sports. It was the safest of subjects.

When we spoke on the phone, my dad, after whom I was named in English, was in the hospital in New Haven, Conn., first at Smilow, a cancer facility, and then at St. Raphael’s, which has become part of Yale-New Haven Hospital, where I was born.

My dad’s voice was usually wispy from all the medication he was taking and from fatigue. But he could still get quite animated when we talked.

We talked about Super John Williamson, a basketball legend from New Haven, who turned in a dominant performance in the final half of the final game in ABA history. I had e-mailed my dad a video clip of Super John’s 1976 highlights about a month ago, before my dad went to the hospital.

In one of our recent chats, my dad agreed that, even more than Julius “Dr. J.” Erving, Super John led the New York Nets at the end to that 1976 ABA championship.

“He had the swagger, and he could back it up,” I said of Super John, and my dad concurred.

My dad, who graduated with honors from Tufts and Columbia Business School, thought very highly of Yale and its sports pedigree, so, when we talked about sports, we often did so with a Yale resonance, going back to my father’s childhood and earlier.

We spoke of Hank Greenberg, the Detroit Tigers slugger, who set a standard for Jewish athletes when he refused to play on Yom Kippur. He led the Tigers to two World Series titles and came close to breaking Babe Ruth’s then-single season, home run record, when he hit 58 one year.

As it turned out, both of Greenberg’s sons went to Yale, one of whom, Steve, played minor league baseball. Steve Greenberg later became a sports agent and then an assistant commissioner of Major League Baseball under the late Bart Giamatti, who had previously served as Yale’s president.

I reminded my dad that, when he took our family to Florida in March 1981, when I was 15 years old, I briefly met Steve Greenberg at a resort near Bradenton, where we went for brunch. He was seated next to Bill Madlock, a great hitter with the Pittsburgh Pirates, who at the time was, I believe, one of Greenberg’s clients.

My father remembered that Madlock was very kind to my brother and me.

My dad and I talked about Walter Camp, founder of modern American football, who played, captained and coached at Yale, starting in the 1870s, and we talked about Amos Alonzo Stagg, one of Camp’s disciples in football, who refereed the first five-on-five basketball game.

I told my dad that Stagg had taught football to the future founder of basketball, whose name escaped me at that moment, while we spoke on the phone.

My dad remembered that it was James Naismith, who invented the game of basketball in Springfield, Mass., not far from where my dad was born in Worcester.

I said to my dad that New Haven, for a small city, packed a mean punch, a variation on something my father often said about Worcester.

I added that New Haven in fact punched above its weight.

My father said that he liked that expression.

“You know who also punches above its weight?” said my father, who not long ago received from me an e-mailed audio of “Neighborhood Bully,” Bob Dylan’s ironically titled Zionist song.

My dad then answered his own question. “Israel,” he said.

Though my dad never visited the Jewish state, he felt a strong tie to it. He told me about an idea he had for solving the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, in which Palestinian refugees could live in Saudi Arabia, where some of that desert space could be cultivated.

If I can put aside geopolitics for a moment, the person I know who may have best replicated Israel in punching above his weight was my father.

My dad lost his own father to suicide when he was 9 years old, but my dad never gave up.

I often told my dad that his life was a testament to fortitude, endurance and tenacity. And it was true. My dad kept persevering and persevering through a traumatic childhood, through years of struggle financially, until he got a job on Wall Street, through two bouts of MRSA, kidney cancer, knee surgery and other ailments late in his life.

My dad and my mother, a public schoolteacher, had next to no money for a number of years after they got married, but they made a life for themselves and have provided not only for my brother and me but also for my brother’s three children.

In recent months, as my mother told me, my father stopped eating most of the time, though he did enjoy nibbling on chocolate ice cream and slurping ice-cold orange juice. His loss of appetite was due to chemotherapy, his weakened immune system and the cancer itself.

But my dad retained his sharp mind, the mind of a heavyweight. When my dad and I spoke on the phone, he told me that the Hart Trophy, given out by the NHL to the league’s most valuable player, was named after a Jewish man from Canada.

I looked it up, and my dad, again not surprisingly, was right.

And yet nothing may illustrate my loving but complicated relationship with my father better than a conversation we had years ago when I was struggling to find my way in New York in late 1987, not long after I graduated from college.

This was before I got a job in 1988 at the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, where I created the “Baseball Ferry,” a waterborne transit service that took fans from various locations in New York to the World’s Fair Marina for New York Mets games.

My father would end up filming me, when I gave the keynote address at the opening of the “Baseball Ferry” down at Pier 11 in the summer of 1989.

But, in late 1987, my father, by then a vaunted money manager on Wall Street, was not so happy while we walked down a midtown Manhattan street with my mother.

As I wrote earlier, my father and mother had next to no money when they got married, and it was only after they had been married for five years, when my dad got a job as a research analyst at Dominick & Dominick, that they could afford to have a child.

Despite or perhaps because of my father’s modest beginnings, he seemed to have little patience for any career that was not remunerative.

On that weekend day in 1987, my dad, who in his early years on Wall Street in the 1960s became Larry Tisch’s go-to guy for stock ideas, expressed his bafflement as to why I cared so much for Hamlet.

While my father could be quite creative, even visionary, in evaluating companies (he could see the future, for instance, in cable stocks long before most people), he could at times be a bit reductive or off-base when he discussed literary matters with me.

“What is it with Hamlet? I’m trying to understand him,” said my father with a smile on his face.

Showing the influence of the late Harold Bloom, who had been my professor during my last semester at Yale, I said that Hamlet could not be easily explained or contained, that you could not limit him.

That was when my dad said, “I’d fire Hamlet!”

In all of our exchanges over the years, that had to be one of my dad’s funniest lines, all the more so because of its irony. My father did not really intend any humor.

He was a tad upset that I wasn’t working on Wall Street, a tad upset that I had quit a job that he had gotten for me.

But, mostly, my dad, who was such an astute and honorable money manager that his clients would later include Paul Volcker, was upset at issues that had nothing to do with me.

My dad was upset at his own father, who, as I noted earlier, had committed suicide when my dad was 9 years old.

While my father sometimes seemed to have the rage of King Lear, a Lear who rejected Hamlet, if not Cordelia, it never escaped me that my dad was still the little boy, the latchkey child, who had lost his own father and lost him so brutally when he was just an elementary school student.

In spite of the anger that my father could show, he could also be quite joyful with me. He was the one, for instance, who introduced me to baseball. He spellbound me with tales of the Oakland A’s, the mustachioed gang of Catfish and Reggie, Vida Blue and Blue Moon Odom.

I fell in love with that team, just as I fell in love with Warner Brothers movies from the 1930s and 1940s, which my father, in a stroke of genius, ushered into my life in late 1971 when I was just 6 years old.

He did not know why I was so depressed as a little boy, and neither did I.

But my father knew he had to do something to fill the void, and he made a brilliant, imaginative leap by bringing Errol Flynn, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield into my life.

I can still picture my dad awakening me at 2 a.m. when I was about 8 or 9 years old, so that I could watch The Adventures of Don Juan, one of the few Errol Flynn films that I had not seen.

“Robert,” my father cooed from the doorway to my bedroom. He poked his head into my room and added with a lilt, “The Adventures of Don Juan.”

Years later, when I told a professor from college about how my father had passed on his love for Warner Brothers films to me, my professor said, “What a gift!”

I told my father of that compliment. It seemed to make him happy.

In the past 20 years or so, as I recovered from two psychotic breaks in the late 1990s, my dad no longer had to worry about me.

He knew that I worked as a journalist.

And he knew that I had largely healed in recent decades from my diagnosis of schizophrenia and major depression, due to the love of my wife, Barbara, who passed away last September.

During my 23 years with Barbara, my angel, I became a much happier and healthier fellow, a Jewish Hamlet, tamed by my own Bathsheba with her elements of Cleopatra and Rosalind from As You Like It.

In recent days, when my dad and I spoke on the phone, we did not talk much about the news, nor did we speak of literature.

We again stuck mostly to sports, the safest of subjects and one that truly reminded my father of some joyful times he had when he was younger.

I brought up the names of Yale football players from the past, like Kevin Czinger, a modestly built lineman in the late 1970s and early 1980s, whom Yale’s longtime coach Carm Cozza had said was the smartest, toughest and best player he ever coached.

My father, who, as I noted earlier, was quite drowsy from all his medication and chemotherapy, had lost none of his mental acuity. He said that, with that last name, Czinger was likely of Czech descent.

We talked about Delaney Kiphuth, my high school history teacher, who had been Yale’s athletic director for 22 years. I reminded my dad that Mr. Kiphuth, all of 5-foot-six and 160 pounds or so, had, like Czinger, played line for the Yale varsity.

My dad fondly remembered meeting Mr. Kiphuth, who was a dear friend and mentor to me, and my dad remembered the name of Ducky Pond, Yale’s football coach when Mr. Kiphuth played for the Elis in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

When I brought up Tony Lavelli, a Yale basketball star from the late 1940s, my dad said, “You’re talking about my era.” My dad pointed out correctly that Lavelli had played for the Boston Celtics before he became a professional musician.

One of the few other subjects I brought up in recent days when my dad and I spoke on the phone was my father’s three grandchildren, my brother’s three kids. “Good boys,” said my father.

I told my father that he was a great success, that he and my mother, both of them stalwarts, had indeed made something of their lives, that they had created a family, that they had taken care of each other, as well as the rest of us, and that they could be very proud.

I did not talk much about the time I spent in New York as a young man, but I will now.

In one of my fondest memories of my father, I can still recall glimpsing down from the stage at Pier 11 in the summer of 1989, as I gave the keynote address for the “Baseball Ferry,” the maritime service that took fans to the World’s Fair Marina for New York Mets games.

There was my father kneeling on the pier in lower Manhattan, while he filmed me with a camcorder.

I can still see his face bobbing above the camera, as I spoke. My dad, whom I sometimes called Big Boy or Big Moose, was smiling at me. In fact, he was beaming.

The little boy, who could sometimes act like King Lear, could still appreciate the national pastime and could still appreciate the contribution to the sport made by his son, a Jewish Hamlet.

Shalom, Big Boy, and l’heetraot!

Peace, Dad, and I’ll be seeing you soon!