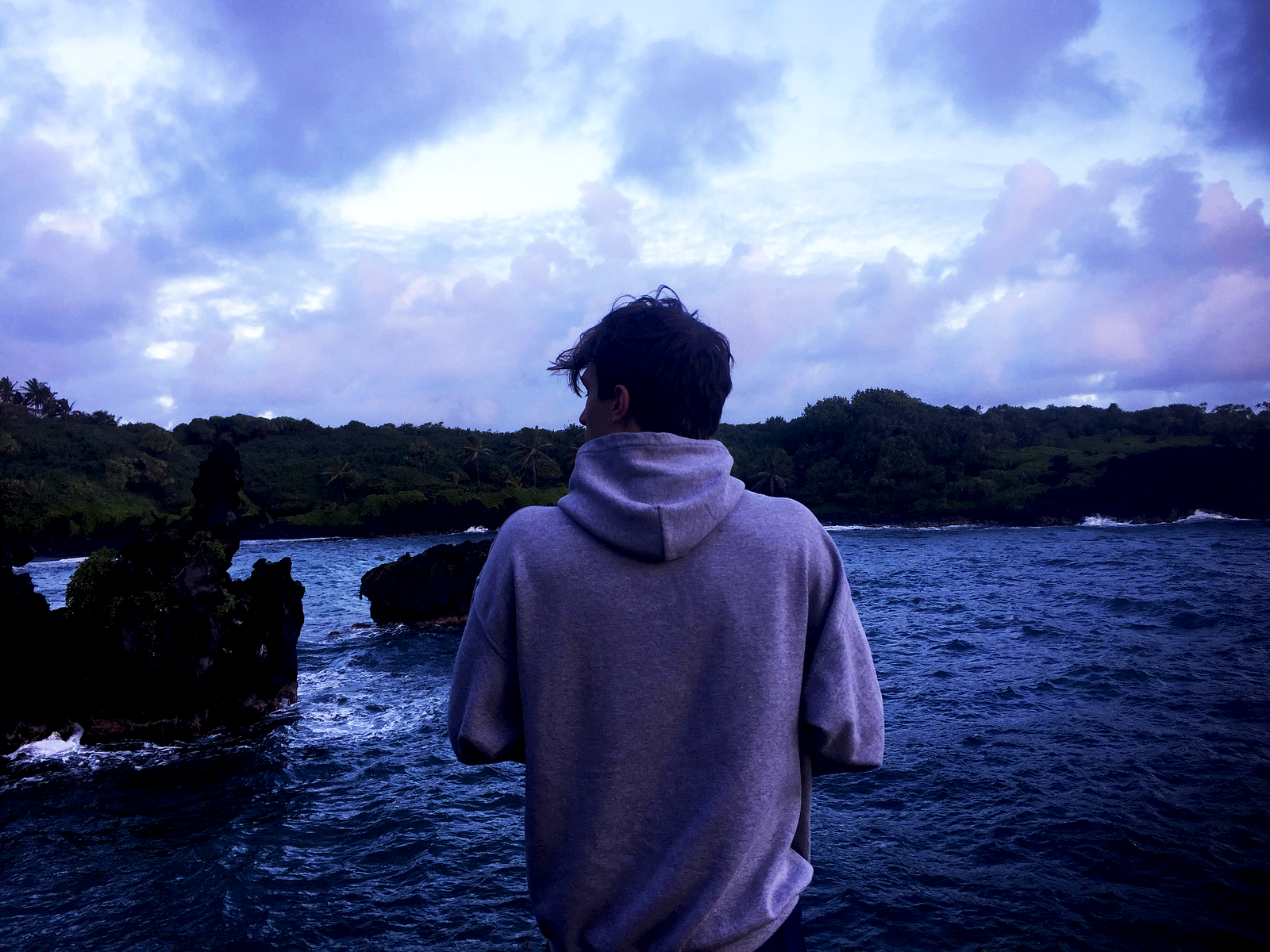

Out in the middle of the Pacific, after driving down hours of peaceful, winding jungle road, we found ourselves watching the sun rise on a black sand beach. The waves were powerful. Save a few stray cats and campers and the groundskeeper’s warm-faced pit bull, we were alone. And we felt humbled, facing the ocean’s force, blasting up through craggy volcanic rock, set against the backdrop of a slowly blue-ing sky. Our small lenses desperately tried to encapsulate the moment, if only to show that we were here.

They say that it’s bad luck to take rocks from Hawaii. The rocks hold souls. And so they stay on the beach, one shiny black body buried by another. With each footstep, they shift, sounding like a crashing wave, but quieter, subtler. As we tried to tread lightly, we forewent the souvenirs, remembering with memory (and photos) alone.

I sat in silence, leaving my two brothers to explore a cave, and watched the waves, letting their unsettling power wash over me. I wondered how such violence could be peaceful. Maybe because it could take what was rough and make it soft, make what seemed permanent, transitory.

As I mused, I glimpsed a white shard poking out from the rocks. It was weathered, softened by the waves, smooth around the edges. Sea plastic. Somehow it seemed pretty in its contrast, albeit strange. I picked it up and played with it. I pondered an artsy iPhone shot.

And then there was another — a white bottle cap, also worn by days at sea. And a twisted thread of faded plastic rope. And what looked to be a piece of a comb. I gathered this small pile and settled it on the tip of a rock. Here’s something, I thought, that could tell a story. Out in this relatively remote, beautifully humbling place were some painful signs of human mistakes. How would I caption this on Instagram?

As my small pile outgrew its quaintness, my thoughts (thankfully) expanded beyond social media, and it became a game. And as soon as I started, I couldn’t stop. What once seemed like a smooth spread of glossy black sand suddenly brimmed with tiny colors, greens and blues and grays and whites too matte to be natural. I started gathering more pieces, piling them on a washed up coconut husk until the husk spilled over. And then there were more. How had I not noticed? With each shard I picked up, my eyes recognized a new shade of imposter, and the pieces seemed to exponentially grow until the entire beach no longer seemed black at all.

Supposedly, hundreds of years ago, the native North Americans couldn’t see European ships rolling in to shore, their brains not recognizing something so foreign. And here, I wondered if it was the same. The unexpectedness of the pollution blinded me to it. All I had seen was untouched nature. And now that the picture was rapidly coming into greater focus, I wanted to cry.

As I grew more frantic, my inner perfectionist was complemented — or eclipsed — by a raw grief, and I crawled around the beach, doggedly collecting everything not black and shiny. Action figure heads and water bottle caps and broken straws and strings and unidentifiable quadrangles, ranging from the size of my arm to the size of a pinky toenail and smaller. The most heartbreaking were disintegrating styrofoam balls, whose pieces blew away and buried themselves deep between rocks beyond my reach. And the most bittersweet were what looked like bits of coral or shell but were featherlight and sometimes had evidence of labels on the back — the ocean’s earnest attempt to assimilate our waste.

As we collected, as we cleaned, we debated a string of classic arguments:

1) “It’s all [insert country name], not us.” (refusing responsibility)

2) “Don’t we have landfills?” (overconfidence in technology)

3) “Someone else will clean it.” (free-rider problem)

4) “Let’s just go enjoy the beauty while we can.” (defeatism)

We fell silent, words quelled by our eyes and emotions, but differently than before, when we had eagerly awaited the first glimpse of golden rays. Peaceful solemnness turned to a grieved one, and the waves maybe seemed a little louder.

Here we were, in the early hours of the morning, building mountains on coconut husks. Each new wave coughed up more pieces, spitting out what it had churned in its belly for who knows how many hundreds and thousands of miles. It was an endless battle. As the sun began to move overhead, our six hands desperately tried to erase the waste from the black sand, suddenly trying to show that we were never here.

This piece was first published on the Planetary Heath Alliance blog, found here. Erika Veidis serves as the Member Engagement & Outreach Manager at the Planetary Health Alliance, a Harvard-based organization that supports the growth of the field of planetary health, working with a global consortium of over 130 universities, non-governmental organizations, research institutes, and government entities in advancing research, education, policy, and public outreach focused on understanding and addressing the health impacts of global environmental change.