One of the sad things about life is that principles can emerge badly from collisions with reality. So it is with the principle that social media sites are not publishers but rather platforms that should not be held accountable for horrible content they disseminate globally. It is starting to dawn on people that this situation is causing huge damage to society, and a critical mass is forming in favor of change.

We’re supposed to love change and the fashionable view is that only a Luddite resists it. But not all change is good; the emergence of social media was itself a huge disruption, and many today regret it. We are probably headed for controls and regulation on the wild circus that is social media, which sounds good. But it also smacks of censorship, which sounds bad.

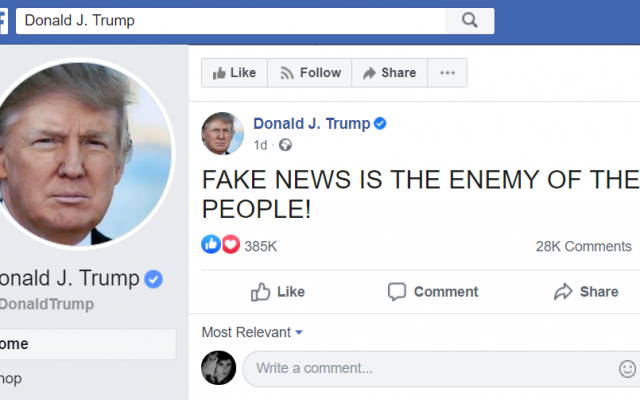

Society faces a critical moment of global polarization, internal contradictions and no good choices. Free speech arguments are being used to defend racism and other evil. Protection from them could easily be abused in the service of despotism by authoritarians. Does anyone seriously doubt that the Trump administration would try to game any regulation of social media to political advantage?

I’ve been sympathetic to the proposition that platforms are essentially neutral, arguing (perhaps annoyingly) that Facebook is merely the biggest microphone in history. A microphone company cannot reasonably be sued for damages; it is the technological conduit of disinformation and not the source of it.

In the United States this idea has been enshrined in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, and its protections have been extended through various machinations around most of the world.

As a result, these natural monopolies have become critical infrastructure on which every little Hitler has been awarded the biggest Nuremberg rally ever. How much damage will we tolerate? We surely would not accept the destruction of all life. What about the widespread undermining of democracy? Extinction of the news industry? Perhaps the turning point will be a reelection of Donald Trump. Horror at the prospect is why liberals who’d normally side with freedom are urging advertisers to bail on Facebook.

Polite society wants social media platforms to do something. And they try, a little.

Twitter recently toyed with labeling Trump’s more dubious tweets “manipulated,” for example. And platforms have applied some forms of policing. Accounts can be blocked for flagrant hate speech; on Facebook ads deemed “political” are rejected unless the advertiser jumps through some hoops; bot accounts are tracked down and exterminated even as new ones spring up; users can flag each other, causing inconvenience.

No one is satisfied. Flagging can be abused; as anyone whose account was blocked for any reason (including password infractions) knows, there’s little recourse because the scale is too big to economically handle appeals; and the real troublemakers can get around all of it without difficulty.

Correctional efforts have mostly focused on the privacy aspect of free platforms trading on the value of user behavior data, which was the easy part. The European Union’s 2016 General Data Protection Regulation has blanketed the internet with pro-forma cookie-accepting banners which most people impatiently click past as soon as they appear. But privacy is better preserved.

Future ambitious avenues may include forcing platforms to charge for access and ban most advertising. Or requiring complete transparency of algorithms and a speedy and open handling of complaints – as one would expect of any public utility. Also on the table might be limiting extreme concentration of wealth and control, forcing divestiture by a few tech titans who today wield more power than most countries.

Some want to also attack scale, which is legally challenging but conceptually simple, and probably is wrong. There is value in competition, but mostly in early jockeying as happened with Facebook and MySpace. To enforce it clashes with the dynamics of the Internet, which tend toward monopoly. Everyone who wants their work history visible has an interest in being on the same platform as recruiters and vice versa, so LinkedIn is a monopoly. The network effect, in which each user adds to the value of the thing, is more powerful than the need for competition. Facebook is a natural monopoly for the demographic defined by adults who find Twitter ridiculous and TikTok infantile. We go there because almost everyone – an old flame, a long-lost friend, a person we just met – will likely be there too. Break it up and we’d have to post every kitten photo over and over – while most will agree that once is surely more than enough.

The real issue, though, is regulating content. Students of history are supposed to oppose censorship, but that has limits. We cannot allow every hooligan to shout “fire” in a crowded theater. But where to draw the line? Should we ban falsehoods? Obviously not. But what about denying the Holocaust (Facebook is being urged to take action on this issue in recent weeks)? The Armenian Holocaust? Denials of climate science?

And who should do the regulating? Do we want the censor to be Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Reid Hoffman or other tech tyrants? The idea of global discourse being regulated by Zuckerberg – who presents as a gargoyle algorithm – is unsettling to many of his own users. Who else though – governments? Few who have experienced state restriction of speech would recommend the experience.

A common proposed alternative is public oversight by expert committees. These can be gamed, toothless, corrupt and inefficient – but some version will probably be tried. It might be paired with more power for the courts, including against the platforms; to date, that liability has mostly been borne by individuals – a partial solution with partial results.

Our emerging universe is one of sometimes universal and often fuzzy jurisdiction, in which the sensitive are offended by half of what they read, and where you never know which country’s servers hosted a megabyte of calumny for a nanosecond. It is a universe in which both social media companies and individuals can expect massive pushback – somewhere, sometime, then often.

Will everyone be more careful out of fear? Such a new equilibrium sounds like a hassle, it doesn’t seem so free, and many will recoil. But it will also find defenders.

“We may have developed the means in the past fifty years to manipulate people to a degree of precision and reliability that make free will impossible,” says my friend, the London-based American economist James Gutman. “Perhaps pure capitalism and democracy – free exchange, free speech – are as unsuited to the digital era as feudalism and monarch were to the industrial era.”

If he’s right, that’s a tragic reflection of the human condition in 2020. Regulation may suppress evil, but it can easily be abused in a traumatized and polarized society, and it will not make us less evil. A more civilized civilization needs education, material and moral. I say get on social media, forget the cute pets, and argue for once for that.