“If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.”

~ Maya Angelou

Words are powerful. A label can invite someone into the family or further other their otherness. David Eagleman’s famous study of how a one-word label can unconsciously lead us to care more for someone from “our tribe” and rejoice in the hurt of someone from “their tribe” suggests that few of us are immune.

Labels often come in terms of race or gender appearance or physical descriptors. Terminology gets into the lexicon often without clear understanding of its origins. Assigning labels and categories are often determined not by those being assigned into said categories. As a result, we may take on the labels ascribed to us by others and then scramble to find meaning and a sense of belonging with a reconfigured identity. It’s confusing enough for adults, but when children are assigned – or reassigned – labels without being asked about who they are and without their context, we may be stripping them of their voice and agency.

For Earth Week 2021, I had the privilege of moderating a discussion around (re)centering Indigeneity in the work around climate change for Six Second’s Climate of Emotions retreat. Interestingly, when the word “(re)centering” comes up, our tendency is to think that inviting one voice means pushing out another. Rather than thinking from this deficit model devoid of context, it is about adding and expanding the many different ways of knowing and being that actually reminds us of our interconnectedness and interdependency.

One key theme that came out of this discussion was that each of the speakers who represented multiple identities and “labels” introduced themselves by first acknowledging and contextualizing their histories – going centuries back – before sharing who they are now and where they are going. They each claimed their own labels rather than one assigned to them by social media lexicon sprung up in an attempt to distinguish the “Other” from the “default.” This seemed to be distinctively different from the usual, Western approach of “this is who I am now” with perhaps a quick acknowledgement via “fun fact” of their hometown.

The Māoris have a term, “whakapapa,” the principle of sharing the names of their ancestors, their lineage, and the geographical area from which they come. This principle is a way not to separate the self from others, but to demonstrate the interconnectedness of one person to an entire ecosystem. By acknowledging our identities in the context of others, we find greater connection with how our past connects to how we move forward. Our understanding of the self cannot be devoid of our context.

It is also a way to emphasize the importance of knowing one’s roots. When someone looks like they are from “somewhere else,” the question is often “where are you really from?” We often do this to make meaning. After all, our brain likes to make sense of the unknown by categorizing. The consequence, unintended or not, can be to “Other” those already othered. Interestingly, when the question is returned to an asker who isn’t an “Other,” there often is a pooh-pooh dismissal of oneself, “oh, I’m a hodgepodge. I’m nothing.” Such a response is fascinating, as it can be a hodgepodge of declaring who gets to be the “norm,” and/or an element of expressing envy of others who know their histories. Add to this complexity is the reality that, due to forced enslavement, migration, or genocide, many don’t know from which they come. Others, due to assimilation or adoption, have not had the opportunity to learn about their origins.

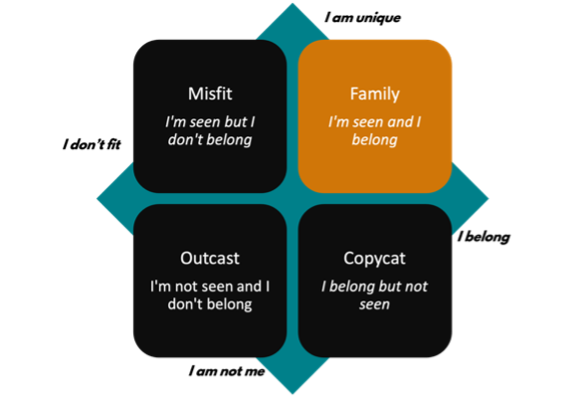

Yet as important as it is to learn our ABCs, we may consider encouraging our students to get curious about the many different roots that shape and inform who they are, such that they can collectively build a more connected planet. Finding our unique identity to find a greater sense of belonging seems like a total contradiction. But it’s not. What underscores our sense of efficacy, agency, and collective responsibility is a need to belong and be valued for what makes us each unique – not in spite or despite our differences.

The Akan of Ghana have a term, “sankofa,” which is about the wisdom found in learning from the past to ensure a strong future. If we don’t acknowledge from where we come, it becomes more challenging to understand how we belong, which is a threat to our sense of identity, an underpinning of Social Identity Theory. This need for “connection” is one of the “8Cs” of compassion.

While a tree may grow even in shallow soil, it cannot weather the inevitable storms without strong roots. An oak tree with deep roots is very much an oak tree. And yet it doesn’t exist in isolation but in an entire ecosystem. It thrives because of the birch and the pine, the squirrel and the chipmunk, the moss and the mycelia. And as much as it draws nourishment, it also contributes to the health of that ecosystem.

So what might we do to support our students to (re)claim their histories such that rather than use labels to divide, they leverage their uniqueness to contribute to and build a healthy and collective ecosystem?

- Acknowledge ancestry

For some, ancestry is more clearly defined or documented. For others, attempts to wipe it out have been systemic. Rather than dismissing one’s identity with “I come from nowhere,” or otherizing Others with “where are you really from,” encourage students to get curious about their roots and their ancestral contexts, however singular or intertwined. Encourage them to explore multiple contexts beyond genealogy. For some, the context may be land-, language-, or culture-based. For others, the context may be something co-created by those who have adopted and embraced them as family. Each of us have stories that precede us. It is through such acknowledgement that we might tap into the wisdoms that have consciously and unconsciously informed who we are today and where we may be heading.

- Build belonging

Labels often serve to divide. Rather, how might we support students to recognize that by celebrating and acknowledging our uniqueness, we can actually find more commonality. Psychological safety is another term that has made it into lexicon of most modern workplaces, which emphasizes the importance of feeling safe enough to show up as our full and authentic selves. That means knowing and being valued and acknowledged for what makes me different, not despite what makes us different. Encouraging students to truly see themselves and others for the unique contribution they bring can build a sense of belonging, not division.

- Cultivate connection

Studies show that diversity of identities alone don’t cut it. We must be intentional about how to mitigate our brain’s mental shortcuts to create commonalities. By acknowledging our roots and the fact that our stories precede us, we can ask our students to uncover the stories of themselves and each other. By sharing story, we are likely to find more commonalities without the risk of erasure and find more uniqueness without the risk of separation.

Incorporating these ABCs may help us to better celebrate how our individuality and identities are interdependent and interconnectedness. It’s a lot of “Is” that can remind us of our shared power to better understand our roots that were planted well before we sprouted so that we can ensure that our actions nourish the soil for a healthier ecosystem for the future.