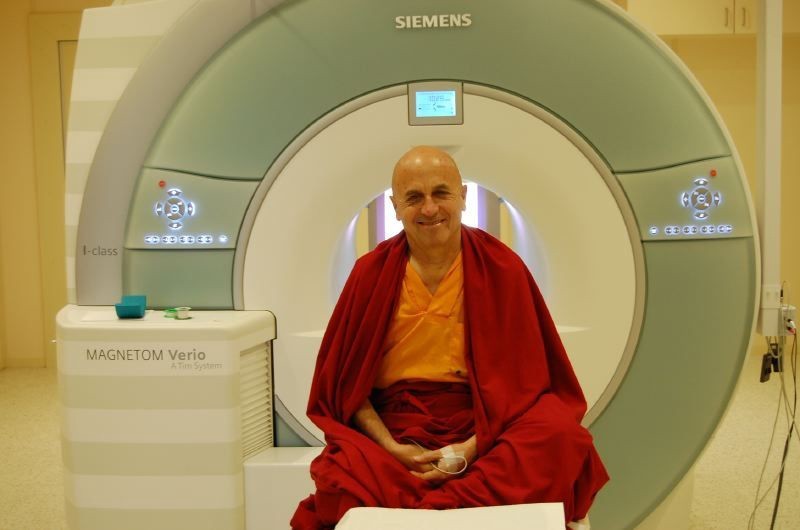

In 2007, along with Tania Singer, I was in Rainer Goebel’s neuroscience laboratory in Maastricht, as a collaborator and guinea pig in a research program on empathy. Tania would ask me to give rise to a powerful feeling of empathy by imagining people affected by great suffering. Tania was using a new fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) technique used by Goebel. It has the advantage of following the changes of activity of the brain in real time (fMRI-rt), whereas data usually cannot be analyzed until later on. According to the protocol of this kind of experiment, the meditator, myself in this case, must alternate twenty or so times between periods when he or she engenders a particular mental state, here empathy, with moments when he relaxes his mind in a neutral state, without thinking of anything in particular or applying any method of meditation.

During a pause, after a first series of periods of meditation, Tania asked me: “What are you doing? It doesn’t look at all like what we usually observe when people feel empathy for someone else’s suffering.” I explained that I had meditated on unconditional compassion, trying to feel a powerful feeling of love and kindness for people who were suffering, but also for all sentient beings.

In fact, complete analysis of the data, carried out subsequently, confirmed that the cerebral networks activated by meditation on compassion were very different from those linked to empathy, which Tania had been studying for years. In the previous studies, people who were not trained in meditation observed a person who was seated near the scanner and received painful electric shocks in the hand. These researchers noted that a part of the brain associated with pain is activated in subjects who observe someone suffering. They also suffer when they see another’s suffering. More precisely, two areas of the brain, the anterior insula and the cingulate cortex, are strongly activated during that empathic reaction, and their activity correlates to a negative affective experience of pain.[1]

When I engaged in meditation on altruistic love and compassion, Tania noted that the cerebral networks activated were very different. In particular, the network linked to negative emotions and distress was not activated during meditation on compassion, while certain cerebral areas traditionally associated with positive emotions, with the feeling of affiliation and maternal love, for instance, were.[2]

Only Empathy Gets Fatigued, Not Compassion

From this was conceived the notion to explore these differences in order to distinguish more clearly between empathic resonance with another’s pain and compassion experienced for that suffering. We also knew that empathic resonance with pain can lead, when it is repeated many times, to emotional exhaustion and distress. That is the burnout that nurses, doctors and staff often experience, the ones constantly in contact with patients in great suffering. It affects people who emotionally collapse when the worry, stress, or pressure they have to face in their professional lives affect them so much that they become unable to continue their activities. Burnout affects people confronted daily with others’ sufferings, especially health care and social workers. In the United States, a study has shown that 60% of the medical profession suffers or has suffered from burnout, and that a third has been affected to the point of having to interrupt their activities temporarily.[3]

Over the course of discussions with Tania and her collaborators, we noted that compassion and altruistic love were associated with positive emotions. So we arrived at the idea that burnout was in fact a kind of “empathy fatigue” and not “compassion fatigue”. The latter, in fact, far from leading to distress and discouragement, reinforces our strength of mind, our inner balance, and our courageous, loving determination to help those who suffer. In essence, from our point of view, love and compassion do not get exhausted and do not make us weary or worn out, but on the contrary help us surmount fatigue and rectify it, when it occurs.[4]

When a Buddhist meditator trains in compassion, she or he begins by reflecting on the sufferings that afflict living beings and about the causes of these sufferings. To do this, the meditator imagines these different forms of distress as realistically as possible, until they become unbearable. This empathic approach has the aim of engendering a profound aspiration to remedy these sufferings. But since this simple desire is not enough, one must cultivate the determination to put everything to work to relieve them. The meditator is led to reflect on the profound causes of suffering, such as ignorance, which distorts one’s perception of reality, or the mental poisons, which are hatred, attachment-desire, and jealousy, which constantly engender more suffering. The process then leads to an increased readiness and desire to act for the good of others.

This training in compassion goes hand in hand with training in altruistic love. To cultivate this love, the meditator begins by imagining someone close to him or her, toward whom he or she feels limitless kindness. The meditator then tries little by little to extend this same kindness to all beings, like a shining sun that illumines without distinction everything in its path.

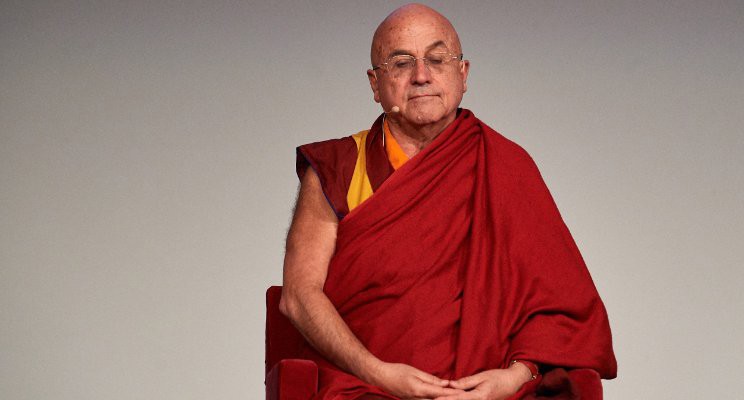

Matthieu Ricard is a humanitarian, photographer, and the author of A Plea for the Animals and Altruism: The Power of Compassion. He is the founder of Karuna-Shechen, a non-profit dedicated to helping improve the lives of underserved communities in Nepal, India and Tibet through education, healthcare and sustainability initiatives. “Karuna” means “Compassion.”

NOTES

[1] For a summary of the 32 studies on empathy with regard to pain, see C. Lamm, J. Decety, and T. Singer, “Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain,” in Neuroimage, 54 (3), 2011, pp. 2492–2502.

[2] The increase of a positive reaction through compassion is associated with an activation of a cerebral network that includes the areas of the median orbitofrontal cortex, the ventral striatum, the ventral tegmental section, the nuclei of the brainstem, the nucleus accumbens, the median insula, the pallidum and putamen, all areas of the brain that were previously associated with love (especially maternal love), feelings of belonging and gratification. In the case of empathy, the areas are the anterior insula and the median cingulate cortex. O.M. Klimecki, et al. (2012), op. cit.; O. Klimecki, M. Ricard, and T. Singer (2013), op. cit.

[3] J.S. Felton, “Burnout as a clinical entity — its importance in health care workers,” in Occupational medicine, 48 (4), 1998, pp. 237–250.

[4] For a neural distinction between compassion and empathy fatigue, see O. Klimecki and T. Singer, “Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience,” in B. Oakley, A. Knafo, G. Madhavan, and D.S. Wilson, Pathological Altruism, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 368–383.

Originally published at medium.com