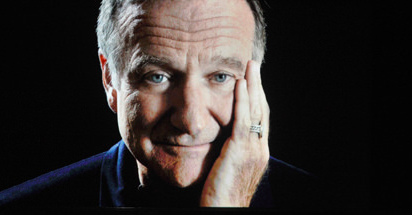

The first response most of us have to news of a suicide is: Why? And certainly the tragic death of Robin Williams was no exception. How could a man who brought so much joy and brightened the day for so many fail to feel the same thing for himself? Robin Williams’ talent, his warmth, his energy, his generosity of spirit and his bigheartedness might have been singular, but his sad decision to take his own life was, unfortunately, all too common. And it’s a heartbreaking decision that more and more people are making every year. So while of course each instance of suicide is different, and while the reasons that people choose to take their own life are complex and individual, as we ask “why” about Robin Williams, we should also broaden the question. Why tens of thousands of people? What is happening that so many people make this irrevocable choice? What are we missing in our culture? How can we open up the conversation on this issue to make other choices seem more realistic and appealing?

In fact, we know more about suicide than our diminished national conversation about it would indicate. Front and center is that, even as many other causes of death are in decline, the rate of suicide is rising. This is especially true among the middle-aged. From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate for those aged 35 to 64 rose bymore than 28 percent. By 2009 there were more deaths by suicide than from car crashes.

A few other numbers:

• In 2011 (the last year for which we have the data) there were 39,518 suicides, making it the 10th leading cause of death.

• Since World War II worldwide rates of suicide have gone up by an estimated 60 percent.

Not surprisingly, the epidemic is especially acute among our veterans:

• An estimated 22 vets kill themselves every day.

• Nearly 20 percent of suicides are by veterans, even though they make up only 10 percent of the population.

And the problem goes far beyond the grim statistics about those who succeeded:

• An estimated 1 million people attempt suicide each year, which, beyond the obvious tragic human toll, is estimated to cost the U.S. economy $34 billion each year.

• More women than men attempt suicide, but men are nearly four times more likely than women to succeed.

• In 2010 there were 713,000 emergency-room visits due to self-inflicted injuries.

• Some 8.6 million Americans aged 18 or older have thought seriously about suicide in the past year.

• In a survey of students in grades 9 through 12, 16 percent reported having seriously considered suicide, 13 percent said they’d made a plan and 8 percent said they’d attempted suicide in the year leading up to the survey.

We also know a great deal about the strong connection between suicide and mental illness. Here too Robin Williams was no exception, having struggled with depression and anxiety.

In fact, around 90 percent of those who commit suicide suffer from a mental illness of some kind at the time of their death — quite often an untreated one. Among the mental illnesses afflicting those who die by suicide, depression is the most common. And overall, it afflicts more than one out of every 20 Americans over the age of 12. As Tony Dokoupil wrote in Newsweek, “In the land that commercialized positive thinking and put pill bottles in every drawer, depression has emerged as the most debilitating condition we face.”

The connection between suicide and substance abuse, something Williams struggled with as well, is also quite strong. Of those who die by suicide, more than one in three is found to be intoxicated from drugs or alcohol at the time. In one study, among adults who’d had a major depressive episode in the past year, those who had also binged on drugs or alcohol were more likely to have had thoughts of suicide and make attempts than those who hadn’t.

Unfortunately, even though we know depression and mental illness are deeply intertwined with suicide, we still don’t treat them as the public-health issues that they are. Since 1986 spending for mental health, while increasing in raw terms, has still remained only 1 percent of the economy, even as overall health spending has risen from 10 percent of GDP to 17 percent by 2009.

So the need is there, but it’s not being met. As the Washington Post’s Sarah Kliff reported, it’s harder to get access to a mental-health provider than it is for any other kind of medical doctor, with over 89 million Americans living in what the federal government considers a “Mental Health Professional Shortage Area.”

One of the primary reasons for this is the stigma still surrounding both mental illness and suicide. This is a very costly silence, and one that has a daily body count attached to it. Only 25 percent of adults with mental-health issues believe people are generally caring and sympathetic to those with mental-health problems.

This lack of attention also stems in part from the legacy of treating the body, mind and soul as separate entities instead of as the integrated whole that they are. For too long “health” — and, along with it, healthcare research and spending — has been about the body and our “physical” health. But we now know there’s no such thing as purely physical health; there’s just health. And the state of our mental and emotional lives is a key component of our well-being — with suicide being the ultimate and most obvious example of what happens when mental and physical health aren’t seen as connected. One study found that 77 percent of those who committed suicide had seen a primary-care doctor in the year prior to their death, but only 30 percent had seen a mental-health provider.

“Twice as many people die of suicides than homicides,” Julie Cerel, the board chair of the American Association of Suicidology, told the San Jose Mercury News in the wake of Robin Williams’ death. “But nobody talks about it. And whenever there is a loss close to us, we feel so alone, and that nobody wants to listen. So when somebody like this dies and is so beloved, it can bring up those feelings of our loss and get us talking.”

And talking is a good thing, because that means connecting. And, in fact, one of the established so-called “protective factors” against suicide is what is known as “connectedness.” The CDC, which says connectedness has “direct relevance for prevention,” defines it as “the degree to which a person or group is socially close, interrelated, or shares resources with other persons or groups.”

Since suicide is the ultimate act of disconnection — from society, from community, from friends and family — it’s not surprising that connection is a powerful roadblock to suicide. We’re creatures of connection. We’re hardwired for it. It’s a fundamental human need. So it’s worth noting that this deadly phenomenon that we know is caused, in part, by feelings of isolation and disconnection has taken off at the same time as the rise of technology that promises us a kind of connection. I’m not blaming technology or claiming any kind of causation, but at least in my own life — and echoed by many people I talk to — the connection provided by technology can often come at the expense of real-life, face-to-face, human connection. And it’s this latter kind that appears to be most important as a protective factor against suicide.

The majority of those who attempt suicide — between half and three quarters — let someone know about their plans beforehand. But are they heard? And would those who tell nobody beforehand reach out if they felt more connected? And would they feel more connected if mental-health issues were less stigmatized?

We know that there are external factors to suicide as well. For instance, suicide rates are often correlated with financial distress. In the U.S. suicide rates were already climbing but accelerated when the recession hit, and in Europe the suicide rate was going down before the recession but turned around when it started. But here too we can see the importance of connection. Financial hardship loosens connectedness: Losing a job can mean losing a social network, and losing a house can mean losing one’s community and, along with it, access to friends. Connectedness can act as a kind of resilience against the environmental factors that contribute to suicide.

So one thing we can do — in addition to demanding increased funding and access for mental-health services — is to try to find ways to increase real connection and engage with those who may feel isolated, cut loose and hopeless. And one way to do that is to put the spotlight on mental-health issues.

This is what Katie Zorn is doing. Writing on HuffPost, she movingly tells the story of her brother Danny, lost to suicide in 2012. Diagnosed as bipolar, he struggled through adolescence. “Danny needed to find a community in which he belonged,” Zorn writes. “It was only when he found the perfect fit that he was able to flourish and achieve academic success.” He found that fit in a performing-arts high school but then dropped out of college. “Danny often wondered then if he should return to college,” she writes. “He needed to regroup, however, and there wasn’t a non-clinical place where he could go and meet people like himself.” She adds, “I believe that had such a place existed, Danny would have found his way back to college.” And, as Zorn writes, there will soon be such a place. Launching this year will be the Fountain House College Re-Entry Program, based in Manhattan. The goal is to serve as a reentry point for people like Danny. “It allows the students a flexible schedule which enables them to pursue their education,” she writes. “They learn the tools of holistic wellness. There is no other program like this anywhere, despite the fact that the mental health crisis within the college community continues to grow.” In other words, it’s an attempt to reconnect with those who feel disconnected.

In an effort to keep this conversation going, our Healthy Living section has just launched #StrongerTogether, which will serve as an open forum on living with depression or caring for someone who is. We’ll be featuring blog posts, news articles, reporting, analysis, opinion and the latest science, and not just from experts but from anybody touched by depression and related issues. “It is hard to turn away from depression after losing (as their family, friends, and we the public just did) two iconic figures — Robin Williams and Philip Seymour Hoffman,”writes Lloyd Sederer in the introductory post. “We have in the wake of their respective tragedies, a moment to face squarely the demon of depression, and to try to ensure the fate of others affected is not a deadly one.” We hope you’ll add your voice to the conversation too, using the hashtag #StrongerTogether.

We won’t ever be able to end the tragedy of suicide, but we can reverse the tide, as we’ve done with so many other health issues in the past. And we can do it in the same way: by making it a collective priority. In this case we can start by ending the stigma around mental-health issues.

Need help? In the U.S., call 1–800–273–8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Originally published at www.linkedin.com.