When I was in first grade, my teacher told my parents that I was aggressive, unruly, and emotional. She said I couldn’t sit still, wait my turn, or follow directions, so my parents took me to a child psychologist. After conducting an evaluation, the child psychologist determined that my acting out was a result of becoming frustrated with school work. She recommended that I see a tutor, and so I did, twice a week for three years. The tutor drilled into me that I needed to take responsibility for my behavior and control my actions.

Back then, and for more than a decade to come, I didn’t know I had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, also known as ADHD. I thought I was slow, lazy, and forgetful. I didn’t want anyone to see me the way I saw myself—as stupid. I spent every weekend, all weekend, studying. I refused to fail, but I still did, and when that happened, I talked to my teachers and accepted responsibility. I blamed myself.

It wasn’t just school that was hard. I had a lot of feelings. (I still do.) I wasn’t always in control of my emotions or my words, which caused problems with friends and family, who didn’t understand my outbursts. I spent a lot of time apologizing and promising to try harder and to be better, not realizing that it was not possible for me without support.

It wasn’t until I was 21, a college graduate who had majored in English, and should have minored in Theater—only I forgot to hand in the paperwork—that I had a breakthrough. My parents told me that my much younger brother had been tested for and diagnosed with ADHD. They made it seem like it was okay to need support. And in that moment I knew I needed help too. Adulthood was different from growing up. There were new rules that I wasn’t used to and couldn’t always remember. There were bills and deadlines and meetings where it was not appropriate to speak up, much less say everything I was thinking out loud. Soon I too was tested and diagnosed with ADHD.

I had a hard time accepting my diagnosis. ADHD symptoms are inconsistent and often invisible to others. Even though a lot of things were starting to make sense, I still had low self-esteem, and I continued to blame myself for everything that went wrong.

Not long after I was diagnosed with ADHD, I took a creative writing class at The New School. Our first assignment was to write about the most humiliating thing that had ever happened to us. Once I started writing, I couldn’t stop, and when I was done for the day, I felt better. Somehow writing down my feelings made them true and real. So, I kept writing. The more I wrote, the stronger I felt and the more I started to understand myself.

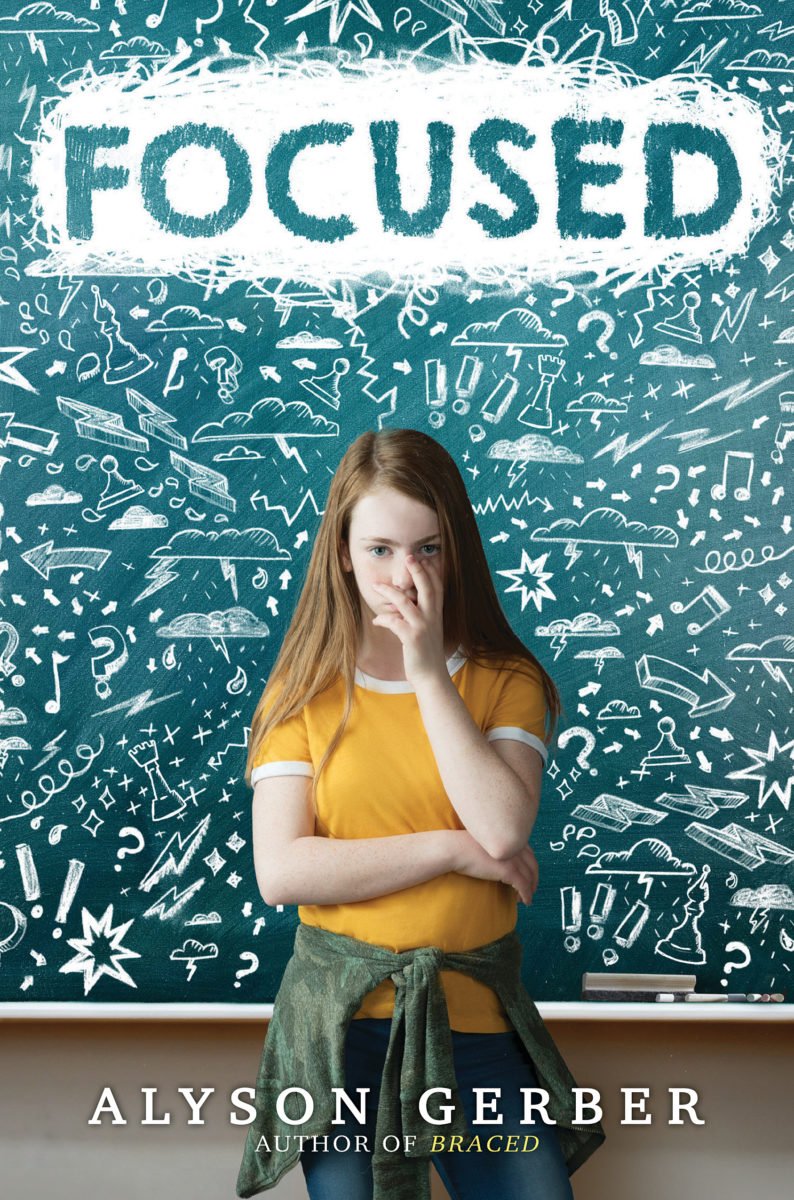

Through the process of writing my latest middle grade novel, Focused, from Scholastic, I began to realize that my ADHD is a unique part of who I am. While ADHD is extremely challenging, it’s also my super power. At a young age I learned how to handle big challenges, and that has made me a more capable and determined person. I’m also not afraid to stand out and be different, because I’m used to it. And I’m comfortable with failure. I know falling down and getting back up will make me better and stronger. Writing for a living might as well be an exercise in failure. Every first draft that has ever been written is bad. It’s usually full of flaws and mistakes. It’s through revision that we make the story, the characters, and the emotional arc come together successfully. And while I can’t always control what I’m concentrating on, I do take advantage of something called hyper-focus. It means that I get obsessed with things, and I can’t think about anything else. That’s how I am about writing books. I can dive right into another world and stay there for a long time.

I’ve used writing as a way to heal, but it’s also allowed me to help others. My hope in writing Focused was that it would give readers a chance to experience what it feels like to live with ADHD and that the book would open up a bigger conversation about what it means to be smart and how we can create space for everyone who has a different way of thinking. A few days ago, I got an email from an educator who had access to an advanced copy of Focused. She explained how she had expected Focused to be a window into understanding her students, but in the process of reading my book, it had actually become a mirror. She herself has since been evaluated and diagnosed with ADHD. When I started writing books, my main goal was to help kids feel less alone. It never occurred to me that I might also have the chance to help adults too.

As someone who had undiagnosed ADHD until I was 21, I know how important it is for students with ADHD to receive a diagnosis, school services, and accommodations. I underperformed in every class and on every test I ever took, because I didn’t have the support I needed, which had a negative impact on my self-esteem and mental health. Recently, the largest study of children and teens with ADHD was published in the Journal of Attention Disorders. Researchers found that at least one in five students with ADHD, who experience significant academic and social impairment, receive no support in school. The lack of services is most significant among non-English-speaking and lower-income students. A week after this study was published, news of the college admissions scandal broke, revealing a very different and disturbing reality: Many parents with financial means had arranged for their children to receive testing accommodations, such as extra time, that are reserved only for students with learning disabilities and disorders, in order to artificially boost their own children’s scores on college entrance exams. By manipulating the system, I fear that these families obtained advantages for their children at the expense of thousands of students who truly need access to, but are all too often not receiving, the accommodations and supports for their learning and attention disorders. When the families faked learning disorders to get their kids into elite colleges, they didn’t just break the law and hurt their kids. They hurt everyone, especially those who are already at a disadvantage.