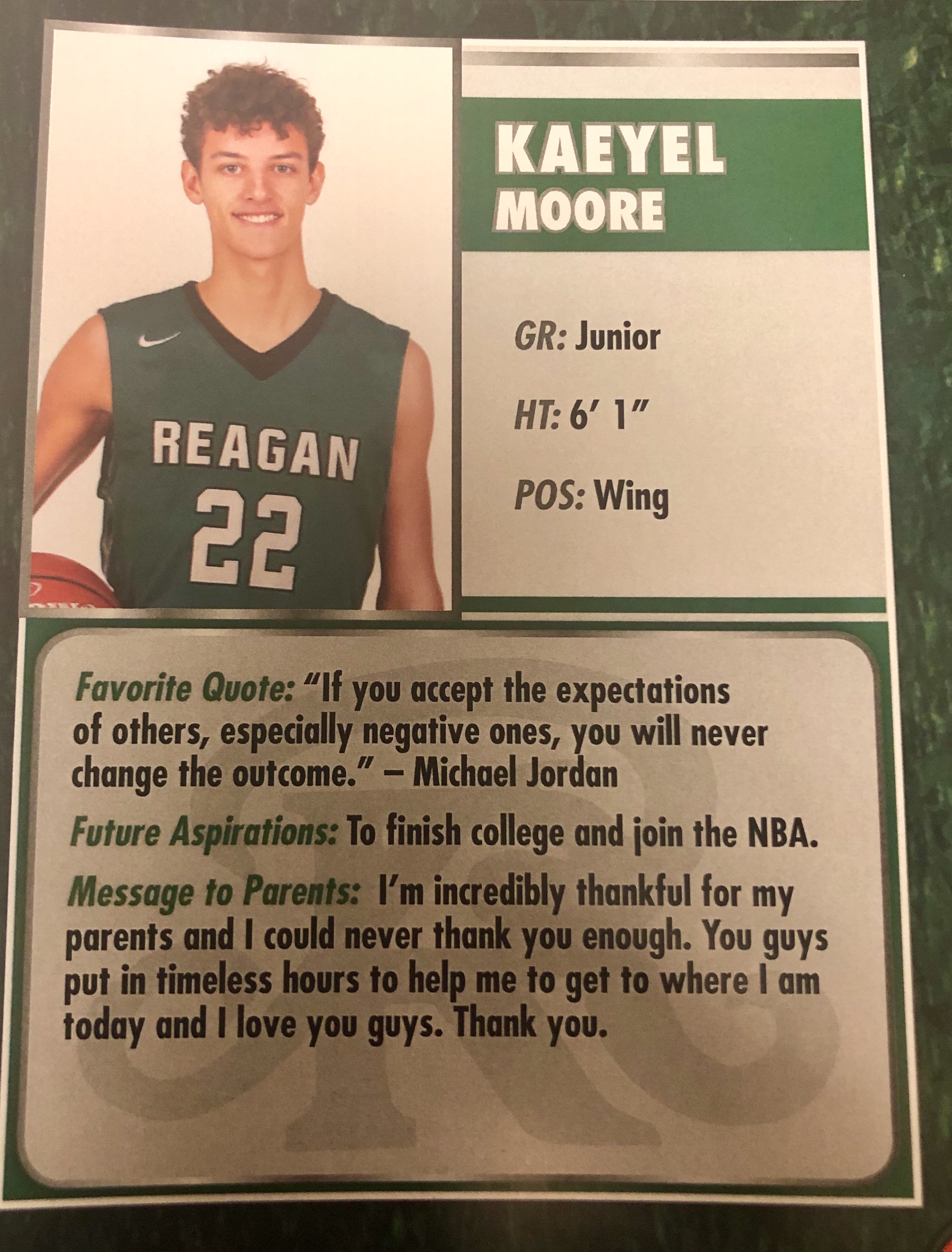

Around this time last year, the basketball coach at San Antonio’s Ronald Reagan High School asked players to jot down their aspirations.

“To finish college and then join the NBA,” wrote Kaeyel Moore, then a junior.

A lanky 16-year-old, Kaeyel (pronounced K-L) was a hard worker still growing into his body. Skilled enough to earn one of 12 varsity slots at a 3,600-student school, a future in basketball seemed possible when he arrived for practice the morning of Jan. 9.

Before even stretching, players loosened up with a slow-paced dribbling drill up and down the court. As he readied for his final round, Kaeyel bent over and tied his shoelaces.

The moments that followed changed everything – for Kaeyel and for countless others.

***

His laces tied, Kaeyel stood and took a few dribbles. Then his world turned black.

The electricity in his heart went out. He was in cardiac arrest. He slumped to the court, his left arm twisted and pinned beneath his body.

About 10 feet away, coach John Hirst heard a thud, turned and saw Kaeyel down. Kaeyel’s awkward position and stillness indicated something more than a stumble. As Hirst approached, he saw Kaeyel twitch and heard a wheezing noise. The teen’s skin was turning bluish-purple.

“He didn’t trip; he’s choking!” thought Hirst, who once had a player stop breathing because he’d choked on gum.

Hirst rolled Kaeyel onto his back and swiped a finger into his mouth to clear the airway. Now he realized it was far worse.

“Go get the trainer!” Hirst screamed to two students deputized for this purpose. At the start of every season, the team goes over how to respond if someone collapses. In every simulation, victims were always a coach, official or fan – never a player; in a lifetime of playing and coaching basketball, that seemed unfathomable to Hirst.

Athletic trainer Joe Martinez ran in, trailed by a student assistant who’d grabbed an AED. Hirst called 911.

Meanwhile, Hirst noticed Kaeyel’s wheezing had slowed. Then came a weak, extended whoosh fitting what Hirst imagined to be a final breath.

Just then, Martinez arrived and said, “Is he breathing?”

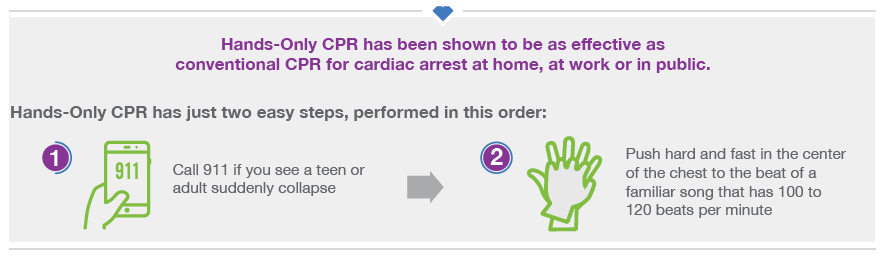

Martinez performed CPR, then hooked up the AED. The machine announced, “Shock advised.” Martinez pushed the button triggering a surge of electricity into Kaeyel.

It was supposed to jolt his heart into rhythm. It didn’t.

Martinez went through it all again – chest compressions, testing whether another shock was needed, learning it was and triggering it.

Martinez was on his third round of compressions when Kaeyel inhaled.

“Other than my two children being born, him taking that breath was the sweetest sound I ever heard,” Hirst said.

Kaeyel heard Martinez’s voice. The teen wanted to speak, but the sound he made was more like a hum. When he pried open his eyes, the world was spinning.

“It felt like I was oversleeping, and somebody was shaking me and trying to wake me up,” Kaeyel said.

In the ER, doctors began the next phase of care: figuring out why Kaeyel’s young, healthy heart stopped.

Eleven months later, it remains a mystery.

“Somehow, everything aligned in that specific way,” said his mother, LaKisha Moore-Hamilton. “The theory is that maybe it was caused by a viral infection. There’s nothing else to explain it at this point.”

***

Only about 10 percent of people who suffer a cardiac arrest outside of a hospital survive.

Often, it’s because the victim is alone. Or surrounded by people who don’t know CPR. Or maybe bystanders are too scared to act.

Maybe there’s no AED around – or, worse yet, it’s on a wall but people don’t know it. Perhaps they’re too intimidated to use it, even though the steps are incredibly simple and the machine announces exactly what to do and when.

Just as Kaeyel was incredibly unlucky to go into cardiac arrest, he was incredibly lucky that it played out as it did. In addition to his chain of survival being executed in textbook fashion, the hospital was across the street from the gym.

And his incredible tale could lead to more lives being saved – in his school district and maybe state, in his mom’s workplace and throughout her company nationwide, hopefully even through retellings such as this.

***

Since Kaeyel’s incident, Reagan High has added more AEDs on campus. Any team leaving campus is required to travel with an AED.

The school district already required annual lifesaver training for coaches. Hirst spoke at this year’s event, encouraging schools to either get an AED or to get more.

“If you can’t afford it, talk to your booster club and your local businesses,” he told them. “And get every coach and faculty member trained.”

At coaching clinics, peers want to hear Hirst tell this story. Again, he uses it as a call to action.

His pitch: “We had a kid that was dead, and he came back to life. Not because of magic or great doctors. It’s because we had great training and access to a machine that is idiot-proof.”

The reaction?

“I think it appropriately scares a lot of people,” Hirst said. “Several coaches around the state have told me they never thought of traveling with an AED. Now they’re doing it.”

Kaeyel’s mom works for Terex Utilities, a company that makes machinery for the electric utility industry. After taking a week off to care for Kaeyel, she returned to her office and asked where the AED was and how many people knew CPR.

The AED was in a remote place. None of the 15 people she supervised had CPR training.

Her San Antonio office now has two AEDs; she reminds staffers monthly where the machines are. Nationwide, the company has stepped up CPR training.

“They have stayed very close to this story and use it all the time as they talk about it across the country,” she said.

Kaeyel and family also have connected with the local office of my organization, the American Heart Association. We provided his family with Hands-Only CPR training kits and were honored to have Kaeyel speak at a Heart Ball. He also was featured in a CPR campaign that included his image on billboards.

At the recent San Antonio Heart Walk, he led a group of about 20 who wore T-shirts that read, “Kaeyel’s Kardio Krew” and had his basketball jersey number (22) inside a heart on the front. On the back was printed, “One heart spared.”

***

Two days after Kaeyel’s cardiac arrest, doctors implanted a defibrillator into his chest. In basic terms, if his heart’s electricity goes out again, the device will restore it.

The next three months, Kaeyel did little more than watch NBA video and play basketball video games while doctors sought a root cause of his cardiac arrest.

Once the most serious conditions were eliminated, restrictions eased. About a week before the start of basketball practice, he was cleared to return – with one catch. His cardiologist requires monthly EKG monitoring. That’s OK with his mom, as it gives her peace of mind.

Once back on the court, Kaeyel looked like a guy who’d been away for months.

His shot was rusty and he lacked conditioning. His thin frame was thinner still, making the defibrillator quite visible on the left side of his rib cage. He’s also haunted by the obvious uncertainty.

“My mind keeps telling me to slow down because you never know what’s going to happen,” he said. “If I start bending over to catch my breath, I’m like: `You need to stand up. The last time you bent over to do something, you passed out and almost died.'”

Saying he is slowly rounding back into form obscures the bigger accomplishment: the fact he’s playing at all.

Kaeyel played in the season opener. He appeared in five of the team’s first 12 games.

“It boggles my mind every time I see him in practice, lifting weights and certainly in a game,” Hirst said. “The other night, I told the official, `Do you remember hearing about that kid who almost died? That’s him, number 22.’

“Every time he’s out there, that’s awareness for CPR and AEDs. If that is his legacy, what a legacy to have.”

But what will his legacy be? When Hirst asks players to jot down their aspirations this year, what will Kaeyel put this time?

“I think he’s come to the realization that maybe he needs to use what he’s experienced to benefit others,” his mom said. “He’s looked at kinesiology and other things related to sports without being directly involved in it.”

Kaeyel, though, isn’t sure what he’ll write. He doesn’t seem ready to give up his hoop dreams.

After all, he’s beaten long odds before.