Before she got a new heart, before she went on Oprah’s network, before her house was remodeled by a TV show, before she enrolled 10,000 potential organ donors, Roxanne Watson wanted to teach history.

She was in her late 20s, having gone from the housewife of a pro basketball player in Europe to a single mom working at a Sears store in New York. Her mother said she needed an education. Roxanne agreed.

Never much of a student as a kid, she loved school as an adult. She got into an honors program. She went from SUNY Rockland to Columbia University, where she signed up for every class taught by a professor who specialized in the Civil War and Reconstruction.

“My great-grandmother was a slave and I met her as a kid,” Roxanne said. “I wanted to study that period.”

College proved too expensive and time-consuming. Roxanne returned to retail. She soon became a store manager with a knack for turning around flagging locations.

“Every place I went, I always had one of the top five in the company in total sales,” she said, listing toy, clothing and department stores where her formula worked. “Once your associates know you care about them, they’re going to work for you.”

One day, Roxanne came away from unloading a truck with a twinge in her side and back. The pain lingered, eventually prompting a visit to an emergency room.

“No, honey, you didn’t pull a muscle,” the doctor told her. “You had a heart attack six weeks ago.”

So began a four-year odyssey that resulted in a new heart – and another new direction for her life.

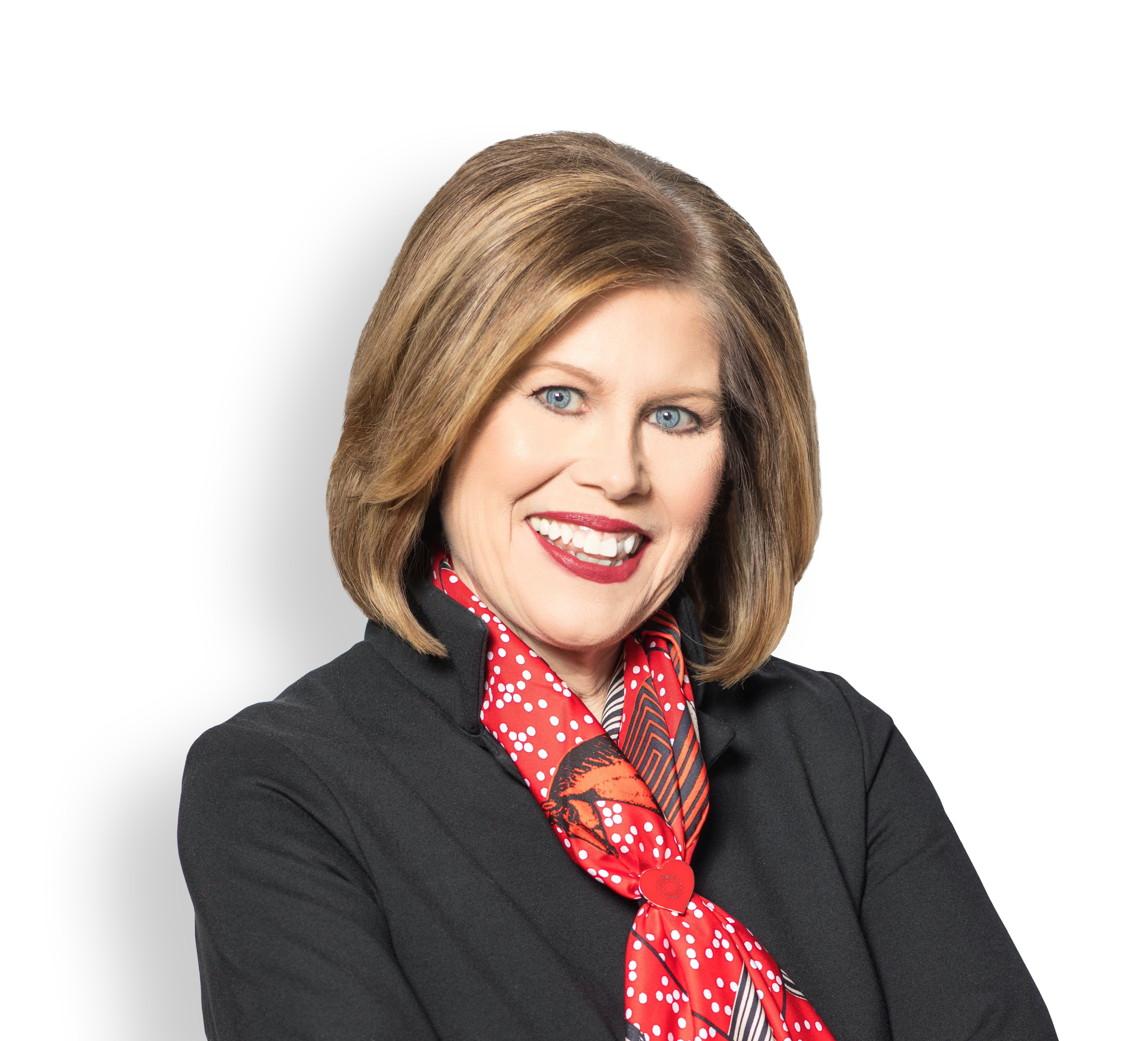

Applying the smarts, savvy and compassion that propelled her in school and retail, Roxanne became a powerful advocate for everyone like her: women, minorities, people with heart disease, anyone in need of a new organ.

It’s quite a list. And she has quite a story, one I’m honored to tell as part of our celebration of American Heart Month. Each February, the spotlight shines even brighter on my organization, the American Heart Association, and our efforts in the fight against the No. 1 killer of Americans.

***

Roxanne was a teenager when her mom had the first of several heart attacks. Other women in the family had heart problems, too.

Yet Roxanne was in her 50s without any problems. She figured she was in the clear.

The diagnosis in the ER changed everything, of course. At 52, she began a health spiral that included countless hospitalizations and procedures. She shriveled from 155 pounds to 95, spending two years on the transplant waiting list – the final 104 days in a hospital – until a perfect match was found.

It was so perfect that she went home nine days later. Yet someone from the hospital asked her to return a few days later. The hospital was hosting an event tied to National Minority Organ Donor Awareness Week and wanted Roxanne to share her story.

***

Her speech went so well that about 20 people immediately signed up to become potential organ donors.

During her months waiting for her transplant, Roxanne heard about donors giving organs to eight people. She did the math and was astounded by the impact she might’ve just had.

Someone from LiveOnNY, the organization that oversees the organ transplant network in New York, was in the audience that day, too, and also realized the impact Roxanne could have. They invited her to speak at the group’s regional meeting.

Someone there heard her speak and invited her to speak at the corporate office.

Meanwhile, Roxanne wrote a letter to Oprah Winfrey. Eleven months after her transplant, she appeared on an episode of “Ask Oprah’s All-Stars.”

With the cameras rolling, she learned the story of her donor.

Michael Bovill was a 23-year-old Coast Guard cadet and volunteer firefighter. He was driving his motorcycle on the George Washington Bridge when a truck cut him off, throwing him from the bike. Having recently registered as an organ donor, he helped save the lives of Roxanne and four others.

Then she met Michael’s family.

***

Roxanne began bringing a framed picture of Michael and a picture of herself in the hospital weighing 95 pounds to her speeches. Now at a healthier weight, covered in a T-shirt that reads “Heart transplant recipient,” she often says, “This is what happens when you get the gift of life.”

Her appearances always yielded new signups. The donor network gave her a final tally each time, while their computers tracked her cumulative total.

When Roxanne learned she was over 1,000, she began setting bigger targets and finding creative ways to reach them.

For instance, she became a fixture at U.S. naturalization ceremonies, averaging 150 signatures per event.

Blood drives are another good location. In honor of Michael’s military background, Roxanne attended a recent blood drive at nearby West Point and signed up 65 cadets.

Because her advocacy efforts often bring her before lawmakers, she always carries forms for them to sign. She laughs at what a perfect setup this is: Public servants given the opportunity to further commit themselves to their constituents, often with reporters watching. It’s worked with city councils, state legislators and, last month, the incoming freshmen Democrats in Congress.

And when a New York TV station did a story about her hitting 10,000 enrollees, the reporter signed up on the air.

***

On July 11, 2011 – her first “heartiversary” – Roxanne threw herself a party. Everyone who hadn’t already signed up to become a donor did that day – more than 150 – including her close friend Terrance Parks.

When Parks died a few years later, his partner called Roxanne to let her know his organs were being donated. She received a similar call from a neighbor whose husband died in a car wreck.

“I’m not a doctor or a nurse, but I know I’m a lifesaver,” she said.

Roxanne’s mom was a nurse; in fact, she worked more than 30 years at the hospital where Roxanne received her new heart. One of the many life lessons she passed along was, “Good things happen when you do good things.” That has played out in response to Roxanne’s advocacy efforts.

Like the time she was invited to speak at the Coast Guard station where Michael had worked. Seeing pictures of him and hearing stories from his colleagues was quite emotional. Yet it was a setup for a larger gift: While there she learned that the TV show “George To The Rescue” would be remodeling her home.

Another time, she started a Go Fund Me page and met her goal through a lump sum from someone who wrote, “From your heart sister, Rosie.” She later learned the benefactor was Rosie O’Donnell, a fellow survivor she’d never met. When O’Donnell spoke at an event in Nyack, New York, Roxanne showed up in hopes of saying thanks. O’Donnell beat her to it, recognizing Roxanne in the crowd and inviting her onto the stage.

***

Roxanne’s bond with Michael’s family continues, too.

A few years ago, she won a contest from a bank offering to fulfill a holiday wish. Her pick: A fancy Christmas dinner for his parents. His dad works at hotel in New Jersey and her mom is the local postmaster, so she figured they deserved someone taking care of them for once.

Then there are the all the awards, trophies and certificates Roxanne has received – more than three boxes full. Every time she gets enough to fill a box, she ships it to the Bovills. It’s a token of appreciation, her way of acknowledging that whatever impact she has is all a byproduct of Michael’s gift.

“Michael’s story is amazing; he helped so many people of different ages, races, religions,” Roxanne said. “That’s the illustration I’m always trying to make. Take the skin off and every single one of us can help someone.”