Photo by Wonderlane on Unsplash

On Easter Sunday he killed himself. My mentor from when I worked on the radio in Dubai and one of my most trusted friends. He had already been low, more of the details are not mine to share publicly but upon landing back in Melbourne at the peak of the Coronavirus epidemic, he was put into quarantine for the obligatory two weeks. There, alone in a hotel room after a decade of living abroad, he ended his life.

At the same time, here in Singapore, it was announced that no visiting between households is allowed and that any foreigners (my partner and I) found to be meeting during this time would have their employment passes terminated and would be barred from entering Singapore again. I spent my 36th birthday alone while the news that these measures and my own isolation would continue for another five weeks. Despite this, I was happy and in this article I explain why.

As a specialist on Human Connection and an advocate of it, I know that any period of disconnection can begin to play havoc with our mental health and I learnt this far before our current crisis. The worst thing was, at that time I didn’t know the science of it, I believed I was the only one going through this. I sent myself crazy with self-loathing that it was only I who was hyper-sensitive and feeling so wretchedly alone. It is with the hope that one person will be released by the information in this article that I write this.

Back in 2014 I, just like my mentor, repatriated back to Australia after ten years living abroad. I can tell you that repatriation alone (without a partner or family) is one of the most isolating experiences a person can go through, and its made worse because no one talks about it. This is the best I can do to explain it, the whole world seems familiar yet distant. Mostly, it’s isolating because you cannot express how foreign everything feels to the people around you because they remember you as you were before you left. Most people do not want to hear about your life abroad, especially in small towns it’s thought of as boasting, it induces envy. Family and friends who never moved or lived anywhere else cannot begin to understand. I felt like I had moved to a new country but all the reasons why I left in the first place remained and the suburban isolation coupled with my mother’s illness was terrifying.

My mother had become paralysed as a result of her stroke and the degenerative disease she has. We knew her condition would worsen. The only option to have great care for her was to get her into a home with 24/7 care. Unlike Singapore, where I was born and am now based, you cannot hire in-house help to care around the clock for a person in a wheelchair. Under Australian policy my Mum is a “two-person assist” which means she needs two carers to lift her to the toilet and back and do all the other amazing things these healthcare workers do for her. We would have to be billionaires to afford two ’round-the-clock in-home carers for her until the end of her life. My sister and I began the shameful process of finding the BEST home for my Mum as she was only 67 at the time.

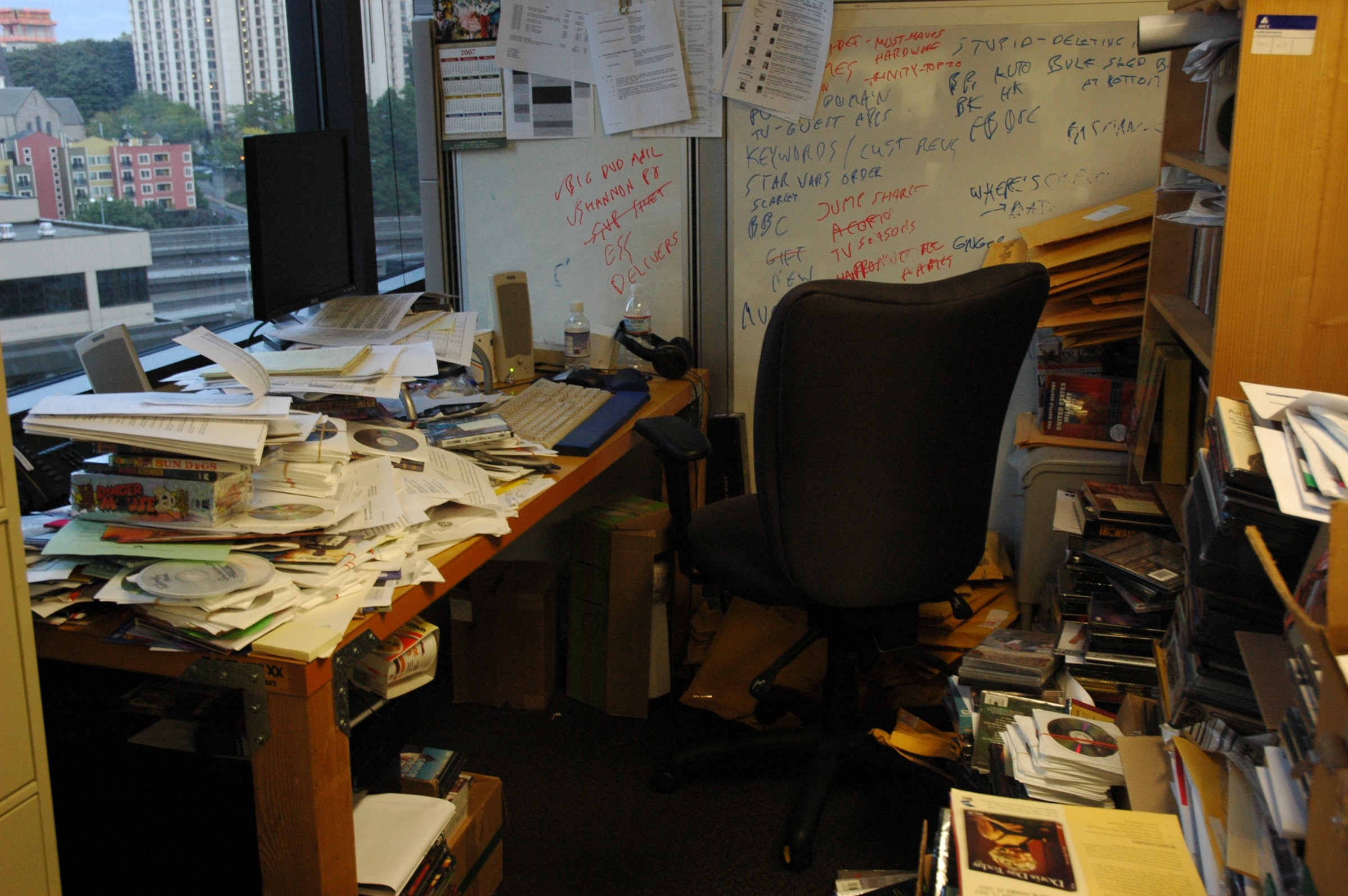

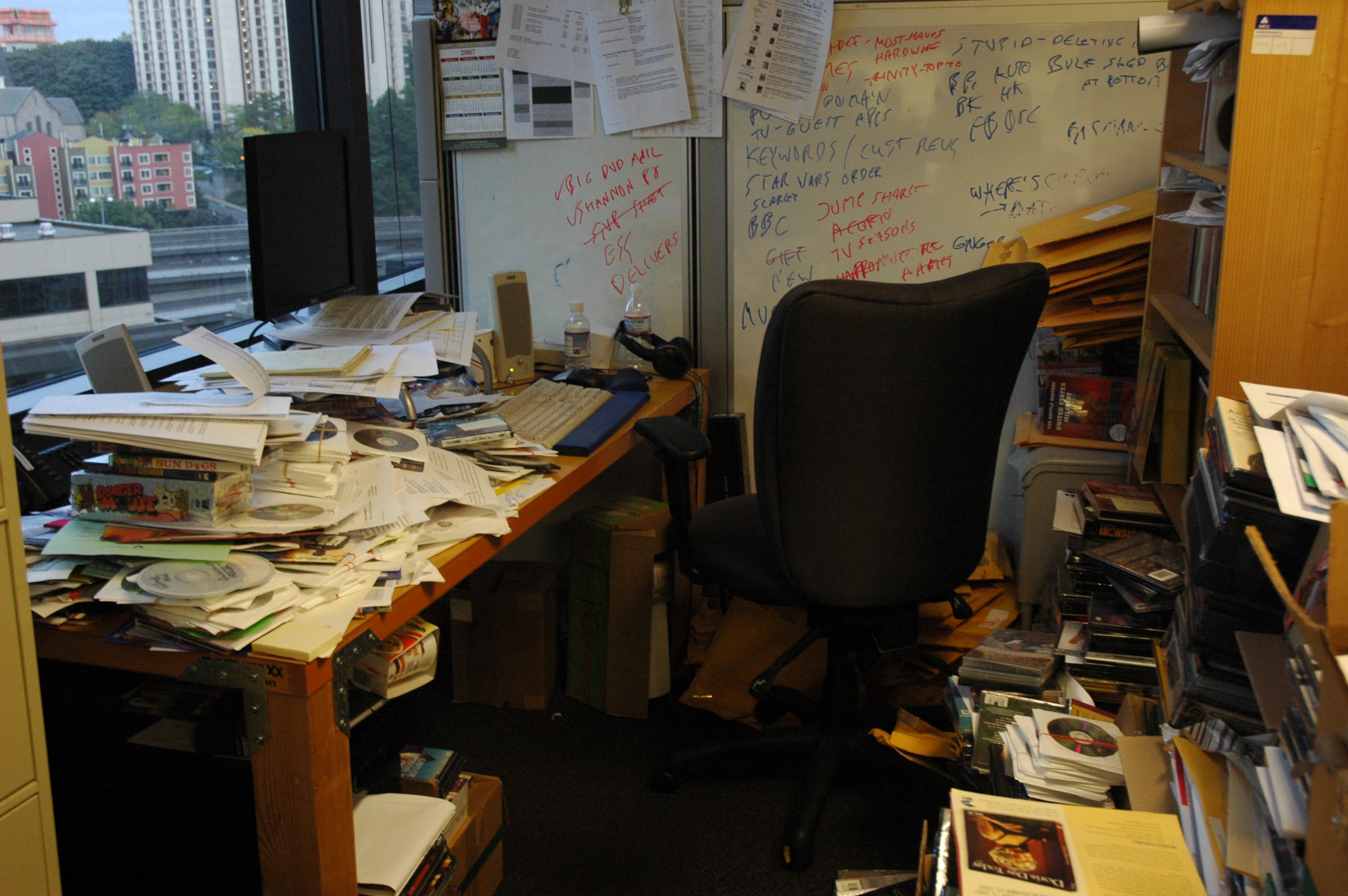

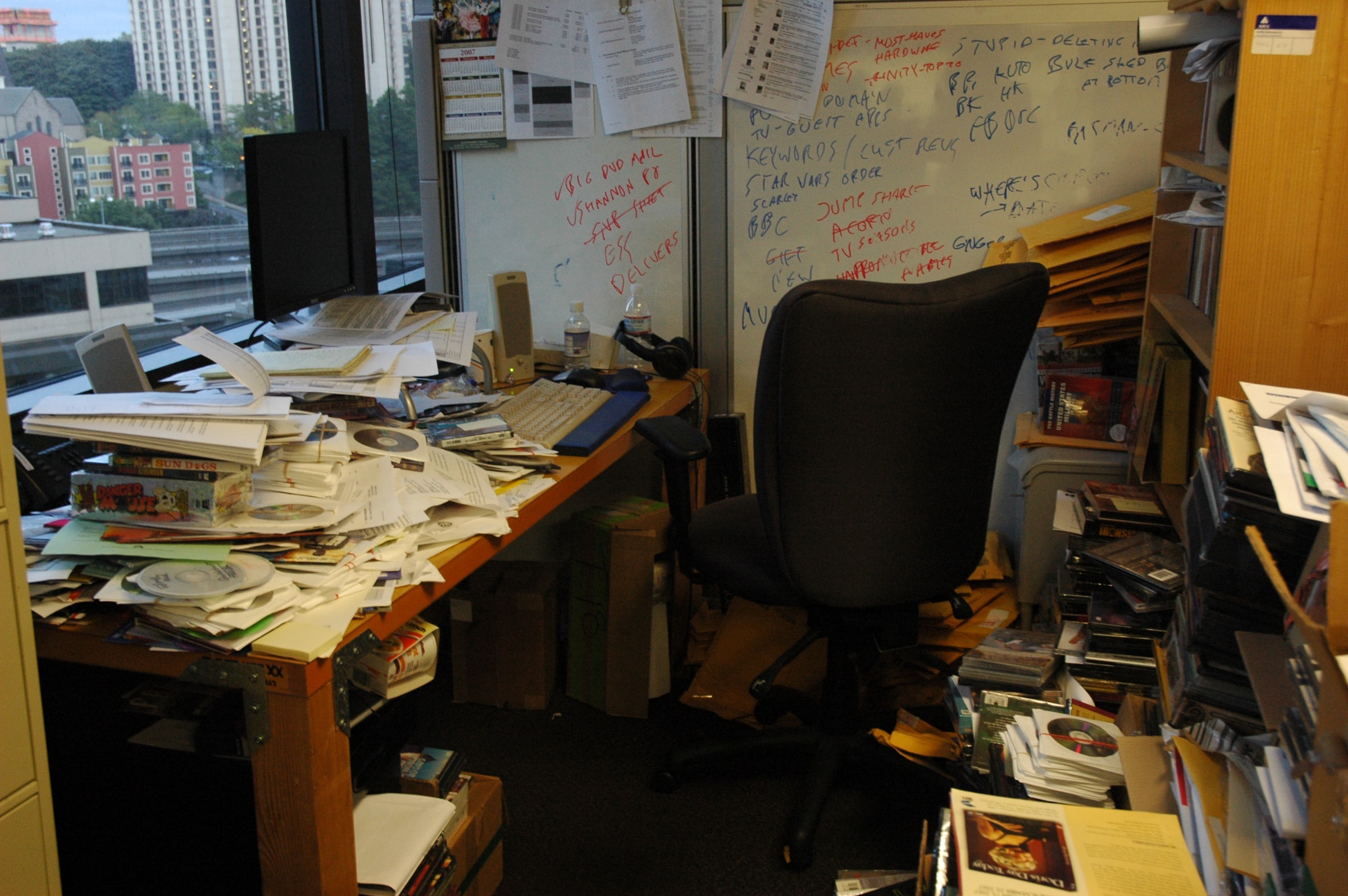

This move came with an additional punch to the face. I had to clean up my eight-bedroom suburban family home and its combined seventy years of hoarding from my mother and my father (who died in 2004). It was penance for me alone to complete, a filial trade-off for the ten years I had enjoyed free from the obligation of being in an Asian family. After my father’s death, my mother had slowly unravelled into her own illness (which has side-effects of depression), insomnia and the sheer grief from losing my father. She resigned her identity. Her new identity at 54 was “widow.” As the rest of her friends leaned back into retirement with their spouses and cruises and grandchildren, my mother learned to be independent for the first time in her life. She learnt to travel alone, do her own finances and simply be satisfied in her own company…or so we thought. What we didn’t see was the fact that this strong, outward-facing persona was a cover for a crippling loneliness. My sister and I both moved out, me as far as I could, to Singapore and then Dubai and for that ten years the piles of things began growing.

Quilting fabric upon quilting fabric, every craft magazine she had ever gotten from my father’s newsagency (long closed) piled high on top of eachother and yellowing with time. What seemed to be every plastic container my mother had ever received from a family gathering was kept, this seemed a ridiculous irony as my mother maybe cooked five times in our entire childhood. Who was she planning to cook for to place leftovers in these containers? It was devastatingly sad, she was waiting for a return that would never happen. When I tell this story to people I tell them that I could see the story of my mother’s disconnection with the world through her possessions. The more they were left to decay and discarded, the more she had given up on life. What I used to see as a pile of clothes were actually sculptures of loss. Hoarding is screaming for help when you feel disconnected, it is an outward expression of an internal pain.

What must have started as a way to fill her huge house from empty nest syndrome, the hoarding began to literally trap her. By the time I came to clean it all up, my mother had filled one whole room with clothes, then had moved to another and another. Until she had nowhere to sleep. Dog pee and animal faeces from her “fur babies” was in every room, permanently staining all the antique Chinese carpets she had migrated with from Singapore. When I finally reached my mother’s bedroom, the site from which all this began, I worked my way down from a breast-height pile of stuff. The door barely even opening to allow me in to clean. When I reached the floor level, having cleaned seven rooms before this, I found that all the magazines lining the floor chaotically were from the year 2004. The year my father died. I looked in a huge plastic bag and inside it was every card she ever received consoling her on my father’s death. Inside the bag was also newspaper clipping after newspaper clipping of the obituary. It was like carbon-dating her unravelling through hoarding. From the day he died, she literally stopped cleaning.

So how did my mother’s disconnection lead to mine. I remember the day I had to clean the bathtub in her once beautiful master bedroom. I was avoiding this tub as it had long become clogged and dark water filled it and paper receipts were floating on top. By this point in the clean-up, I had pushed past any resistance. It just had to be done. What I can tell you for sure is, and I tell my peers who are only going through this process with their own parents now, almost a decade later, is that it’s isolating because only the children of a person can have the right or responsibility to go through and make decisions about their parent’s possessions. Family secrets have been known to emerge from this process. I know a woman who found presents and cards her father had wrapped for his mistress. Another found letters returned from the Vatican where her devoted Catholic mother had pleaded with the church for a divorce. This is why strangers cannot do this cleaning, only you can do this. It’s your last gift to your parents.

I snapped plastic gloves onto my arms, I plunged my hand deep into the water, held my breath and pulled out the plug in that bath. I sobbed. I had gone from an extremely social life in Dubai and constant correspondence on my phone and email to no one calling or writing. That’s the thing about family crises, people outside the family don’t really want to know about you, they want to know about the person who was injured, paralysed, hurt. They don’t really ask you about YOU. People also have their own thing going on and that is totally ok. I had left a full-time job on the radio in Perth as well and for six months had been cleaning nine hours a day. I had gained weight, my hair had thinned and I could no longer even maintain civil conversation with people because the dirt in that house had so unhinged me. I decided, me the most social person in the world, to self-isolate. As I wiped down that shower, all I could think about was Singaporean taxi drivers.

Yes, you heard me right. A cousin had once told me a story about men in Singapore, who after the SARS epidemic lost their jobs due to the recession which followed. Unable to find white-collar roles in their industry, to support their families, they got jobs as taxi drivers. But they were angry. They were doing a job that didn’t match the way they had defined themselves. I was one of those taxi drivers, I was now a cleaner (not the best by any means, I wish I had some training. I still do very streaky glass work to this day. LOL) and I had stopped creating completely. No writing, no painting, no radio…none of the things which I felt defined me. That dirty, slimy bathtub was a sludge-disguised gift. That day and thinking about those taxi drivers, I learned the true meaning of empathy. Never to judge anyone who has anger or rage, they are just wrestling with the unmitigated gap between themselves and the bathtub they are having to clean.

The Covid-19 crisis will create more sludge-cleaning bathtub humans than SARS did. It will require us to delve deep inside us for empathy for those who have lost their businesses, families and identities through this. I also hope you see that this story is one that demonstrates that disconnection is like dominos, my mother’s unravelling, led to mine. It takes just one incident in our lives to bring us from normal, socialised and connected human beings to wrestling with our life in a Melbourne hotel room. We are all that close to the edge.

I write this so you know you are not alone. I write this to let you know, the six-month clean up job taught me so much. Humility, yes. Not to identify my value with my job, yes. Job status means nothing, yes. People contact you often when they feel you can add value to their lives but true friends stay when you are swimming in darkness, yes. But the most important thing this gave me was a complete appreciation for the value of human connection and a new level of resilience I had never felt. Even though I had already seen my father pass in front of me by this point in my life, the isolation that was forced upon me in those six-months almost broke me.

This is why solitary confinement is the worst punishment before the death penalty. This is why. In Netflix’s “Time: The Kalief Browder Story” a sixteen-year old African American is placed in solitary confinement for 800 days for allegedly stealing a backpack. In the third episode of the docuseries, experts describe the punishment as inducing a “break down of the brain.” The United Nations considers any stay in solitary confinement over fifteen days as a form of torture. On Rikers Island, where Kalief was incarcerated, solitary confinement consisted of no human contact at all besides a plastic tray of food slid under the door. Mental health experts in the documentary describe the symptoms of the punishment as: hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, lack of impulse control, increased anxiety, appetite loss, chronic depression, weight loss, sleep problems, heart palpitations and more. Kalief committed suicide in 2015 as a result of the mental anguish born of his experiences in jail. Like my mentor, solitude leaves scars.

This is because we are created to be in a tribe. Our ancestors, early man, knew that the tribe kept us safe. When we were injured while hunting, our community protected us. When we became pregnant and were slow, the other women in the tribe, kept us safe and fed us. This is why our brains evolved to need connection. I’ve spoken about this so many times in my speeches and it’s why when we are separated from each other, we become depressed. Stress hormones like cortisol are released in our brain, this is why we become anxious. During this pandemic, the gift of empathy is being shared, we now all have a small insight into what those wrongly accused in solitary confinement or people who suffer from severe depression feel daily.

In addition to empathy, we are all being gifted resilience. When I was isolated back in 2014, I would literally burst into tears for no reason. I would become enraged in a conversation and swear. In short, the reality in my head was starting to disconnect from the reality in front of me. I had to stop this. I started by observing what I needed to do that would make me feel a little bit better. I would go for a walk outside if I felt really on edge. I began painting again and this was a turning point. I would take a day off from cleaning to paint now and again.

Creativity seems to be the ultimate escape to a better reality, I recently watched the incredible true story of Richard Phillips, a man falsely imprisoned for 47 years, he painted from one water colour set for 20 years and said it saved him. So when Covid-19’s circuit breaker (a VERY strict circuit breaker) was announced in March here in Singapore, I went straight to the art store and I hoarded canvas while other people hoarded instant noodles and toilet paper. I knew what I needed to keep me from unravelling because I had lived it before.

If you are struggling right now with this isolation, I want you to know, it will pass. It is preparing you for something in life you don’t even know yet. Just like cleaning that sludgy bathtub, it is making you more humble, more wise and more resilient. I want you to be around to see what’s next.

This article is dedicated to the incredible C.P. I miss you.