Growing up in Slidell, Louisiana, Rachel Paul Owens considered herself a tomboy. She loved running and chasing other kids, especially if it included shooting hoops or taking swings in the baseball batting cage her dad built in their backyard.

Rachel knew she was a heart disease survivor – the puffy scar in the middle of her chest, often visible above her shirt collar, announced it to everyone. Yet she didn’t know the significance of it. In fact, she considered it so normal that she described the remarkable fact of having undergone open-heart surgery at age 1, and again at 15, with the same tone as telling someone she’s right-handed.

Even after a life-threatening bout with heart failure at 22, Rachel still considered her heart status as nothing more than one of the ingredients in the gumbo of her life.

Then she became pregnant with her second child. Doctors detected a heart problem. He turned out to have the same two defects she was born – and more. He underwent his first heart procedure at 2 months. Then open-heart surgery at 15 months. And another months later.

February is American Heart Month, a time of heightened awareness surrounding the No. 1 killer of Americans, and the No. 1 killer of women, claiming more lives than all forms of cancer combined. Sharing stories such as Rachel’s is one of the ways my organization, the American Heart Association, seeks to inspire others to pay more attention to heart health.

Rachel is a survivor. She’s the mother of a survivor. She’s a daughter who lost her dad to heart disease.

Yet, through it all, she’s maintained a plucky spirit. It’s an attitude best expressed by her motto: “Triumph through your trials and look good while doing it.”

***

Everything started with a cold.

Rachel was 22 months old when her mother took her to the hospital. A strong medication sent her heart into an unhealthy rhythm.

A closer look revealed that she was born with a hole between her heart’s left and right atriums. She underwent an operation to close it.

She continued regular visits to a cardiologist. He later recognized another problem. Her mitral valve wasn’t closing properly, sending blood flowing the wrong way. At the time, it only required monitoring.

All this news jolted her parents, Xavier and Marle’ Paul.

They didn’t know whether to swaddle her in bubble wrap or treat her like they did her two older brothers.

Xavier and Marle’ might have benefited from discussing things with someone else who’d raised a child with heart defects. But they didn’t know anyone.

Marle’ decided to close the Creole restaurant she owned. This enabled her to stay on top of things for all three kids, especially all the dos and don’ts for Rachel. One year, that meant coming to her school every morning to give her a dose of medicine.

That was among many things that could’ve been stigmatizing. Marle’ and Xavier made sure they weren’t.

“My parents never made me feel different,” Rachel said. “I never had any reason to be embarrassed about my health or my scar.”

***

Rachel was 15 when a stress test showed her leaky mitral valve becoming more of an issue. She wasn’t in trouble yet but was headed that way. So she underwent her second open-heart surgery.

After high school, she went to college 2½ hours away, in Lafayette, Louisiana. The day after she settled into her apartment, Hurricane Katrina blew through New Orleans, carried across Lake Pontchartrain and wiped out much of Slidell, including her family’s house. She went home for her second year of school, helping her parents rebuild their lives.

The next year, something else was wrong.

At work, Rachel kept feeling like she was about to pass out. She also had stomach pains.

Her Lafayette cardiologist couldn’t find anything wrong, so he sent her to a gastroenterologist. That doctor prescribed acid reflux medicine. It hardly helped. She changed her diet, yet the problems persisted.

It got so bad that she couldn’t walk to class. Her then-boyfriend, Troy Owens, drove her to the front door of each building.

One day, she was taking a hot shower when she again felt like she might pass out. The next thing she remembers is being on the ground. Second-degree burns on her shoulder indicated she’d been out for quite a while.

Confused and in pain, Rachel called Marle’. Marle’ called Troy.

At the hospital, a doctor recommended implanting a defibrillator into her chest to jolt her heart into rhythm if necessary. Considering how many wrong guesses had gotten her to this point, she wanted a second opinion. She sought it at UCLA, where Troy’s mom worked.

***

Rachel saw Dr. Leigh Reardon, a cardiologist who specializes in adults and kids with congenital heart defects. Reardon wasn’t just new to Rachel; she was among his first patients.

He gave her a vest-like heart monitor to wear overnight. The machine would record every heartbeat; this would show whether she needed a defibrillator.

Rachel was sleeping when Reardon called. He wanted her to return to the hospital as soon as possible.

She was in extreme heart failure. She got the device. She remained in California for three months, regaining her strength while regularly seeing Reardon. Being under the care of someone with his training – a specialty she hadn’t even known existed – provided another kind of strength, the confidence that she would avoid the misdiagnosis that let her heart failure go undetected.

Best of all, no longer being slowed by a weak heart made Rachel feel liberated.

“I could walk and walk up stairs again. I went shopping again!” she said. “I’d kind of forgotten what it felt like to feel normal.”

***

Rachel and Troy married and settled in California, where Troy was stationed in the Navy.

When they were ready to have kids, they went to see Reardon.

“My biggest concern was would it be safe for me to carry a child,” she said. “Because I didn’t want my child to be here without a mother.”

Reardon said one of her medications could cause problems. She had to wean off it. And that would take a year. As for the chances of having a baby with heart problems, the risk was essentially 50-50.

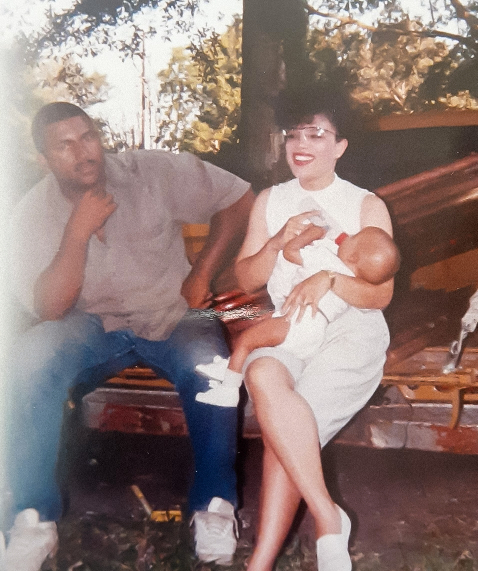

The pregnancy went fine, until a checkup at 31 weeks. Tests showed her unborn son’s growth had slowed; he wasn’t getting nourished properly. She checked into the hospital. Two weeks later, she delivered her son Keith by cesarean section. He went straight to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Soon, mother and baby were fine. The father, however, was “floating in open water somewhere,” stuck amid a deployment. Troy knew he was going to miss the birth. Because Keith arrived early, the boy was 4 months old when Troy first held him.

***

Over the next few years, a lot happened.

Rachel had a new defibrillator implanted (because the battery was running out), the Navy moved their family to Jacksonville, Florida, and she dealt with a glitchy heart rhythm that couldn’t be handled by a defibrillator. She underwent two ablation procedures to correct it.

Once all was well, she and Troy were ready to make Keith a big brother. She became pregnant in the spring of 2018. At her 20-week checkup, the OB/GYN noticed a heart murmur.

Rachel was always braced for this possibility. Now it was a reality.

She needed comforting. She needed advice from someone who’d been through it.

Marle’ and Xavier provided both.

“That made it so much better and easier to deal with,” Rachel said.

The rest of her pregnancy and delivery were uneventful. Eli arrived – with Troy present – in December 2018.

Then came the full diagnosis.

Eli had the same hole in his heart and same valve problem as Rachel, plus a narrow pulmonary valve and an anomalous coronary artery, meaning one of the arteries in his heart was in the wrong place.

At first, the narrow valve was the biggest problem because it limited blood flow through his heart. At 2 months, he underwent a procedure using a balloon to widen the valve.

A year later, doctors decided to fix both problems he shared with Rachel. This meant open-heart surgery.

“My mom was like, `Don’t worry, everything will be OK. Just bring it on and we’ll get it done,’” Rachel said.

The more Rachel talked to her parents, the deeper the conversations went. For the first time, she pressed them on how and why they decided to make her feel like any other kid.

The secret? With a laugh, Rachel said: “To be honest, they just kind of winged it. They had a lot of faith and trusted their instincts.”

It worked, of course. Because her parents didn’t swaddle her in bubble wrap, Rachel never saw herself as fragile. She wants the same for Eli.

Now 3, he has a bit of delay with speech and language. Still, she’s begun destigmatizing his heart problems.

“I have him touch his scar and I show him mine,” she said.

***

Eli’s heart probably will need more repairs. Doctors are optimistic they can wait until his pre-teen years. They also continue monitoring his narrow valve, hoping it grows as he does.

As for Rachel, she’ll eventually need another defibrillator. She’s also likely to need more work done on her mitral valve, although that, too, is likely years away.

However things play out, she’ll be ready for it – especially after the last two years.

Eli’s first surgery came in March 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was gripping the nation. Three months later, Xavier died of congestive heart failure. A few months later, Eli needed another open-heart surgery because of problems caused by some tissue in his narrow valve.

Last year, Rachel represented the American Heart Association as a “Real Woman,” someone whose story and spirit embody the aim of our mission to be a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives. The program is part of Go Red for Women, our initiative aimed at empowering women to take charge of their heart health.

“I want other people – especially other parents and survivors – to know how important it is to stay positive,” she said. “That’s where my motto – Triumph through your trials and look good while doing it – comes from.

“Enjoy life. That’s what I want, and what I want for Eli.”