“Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden path by the lure of little voices, the mysterious fascination of the unknown.” –Sir Ernest Shackleton

In the metaphysics of identity, the ship of Theseus is a thought experiment that raises the question: If a boat, battered by storms, rotted by salt and barnacles, reaches the state that all its original components have been replaced, is it then the same object?

If but a safe voyage is sought, the boat should never leave the harbor.

Yet if the ambition is discovery, or telluric wisdom, or the evolution of consciousness, or even the crasser quests of religious, political, or economic booty, then sails must billow, waves must be crested, risks assumed, and boats broken. The risk/reward minuet comes with the note that one might not come back.

In the Age of Exploration adventurers were most often sponsored souls willing to trade limb and life in search of plum for their backers. This was closer to war than romance, in that participants often lived in mortifying dread, supped on hard biscuits, sawdust and rats, and slept lonely on hard surfaces in hopes of returning to a better life, a bit richer, perhaps with a promotion and some fame. More often than not, these adventures were distinguished by their accidents, either in geographic discovery, disappearance, or loss of life; they were, in essence, well-planned trips gone wrong. Leif Erikson was blown off course during a voyage from Norway to Greenland about 1000 AD and knocked into North America. Nearly five centuries later, Columbus imagined he had arrived in the Indies, when he was half a world away in the Caribbean.

Almost thirty years later Ferdinand Magellan was looking for a western trade route to the Spice Islands when he came to a sticky end in a local skirmish in the Philippines; likewise, Ponce de Leon, Brule Etienne, Captain Cook, John Gilbert and Jedediah Smith were killed by indigenes during their explorations. Vitus Bering died of exposure navigating the northern sea that would bear his surname; Henry Hudson disappeared in his namesake bay after he was put adrift in a small boat by a mutinous crew; and Scottish doctor Mungo Park vanished while navigating the Niger River. John Franklin lost his entire expedition, two ships and 129 men, when he became icebound trying to negotiate the Northwest Passage. And while Henry Morton Stanley survived his 999-day journey across the malarial midriff of the Dark Continent, half of his 359 men did not. Robert Falcon Scott may have been a last of breed, sacrificing himself and his party to an Antarctic storm for the sake of science (he dragged rocks and specimens across the continent to within eleven miles of a resupply depot) and of British boasting rights to be the first to the South Pole (Norwegian Roald Amundsen beat him by five weeks).

The point is, these adventures were decidedly dangerous, and, like enlisting to go to battle, those who volunteered had the grim expectation they might not return. These were individuals willing to go where only dragons marked the map, and to tender lives for queen, country or God, or the trading company. They were saintlike only as martyrs to their own ambitions. If there was any personal gratification or growth that came from the exercise, it was tangential…the central goal was to survive, and come home with bounty, be it new colonies, converted souls, slaves, spices or knowledge.

The next historiographical trend in exploration had its archetype in Richard Burton, who, though commissioned by the English East India Company and later The Royal Geographical Society, really set about exploring to satisfy his own insatiable curiosity about foreign life, languages, and exotic sex. He was a new-fashioned adventurer, who sought out perfectly unnecessary hazards in the name of inquisitiveness and pursued the unknown not for empire or some larger good, but for his own love of discovery.

Ernest Shackleton was another early executant of this sensibility. For his ill-conceived plan to cross Antarctic he had major backers, and promoted his “Imperial” expedition as scientific, though he had no interest in science, even scorned it…the real reasons for the extreme endeavor were personal: he loved a good adventure; loved the romantic notion of searching for fortune; and loved to sing, jig and joke with his mates in the field. Everything else was an excuse.

Others came to personify this type of adventure in a more direct way, such as New Zealand beekeeper Ed Hillary, who clearly had a vast enthusiasm for climbing and was able to parlay it to membership on a high-profile British Himalayan expedition; and Wilfred Thesiger, who loved the desert, and spent forty years exploring its inner reaches, including a crossing of Arabia’s Empty Quarter. When Teddy Roosevelt decided to explore the River of Doubt in Brazil, he said, “I had to go. It was my last chance to be a boy.” It was his passion for adventure that took him to the Amazon, where he picked up the malaria that led to his premature death.

More of late Arne Rubin, who made the first canoe trip down the Blue Nile; Naomi Uemura, the first to reach the North Pole solo by dogsled; and Robyn Davidson, the first woman to cross the Australian desert by camel, personified this indomitable spirit of exploration, those who followed some irresistible inner call to find terra incognita, and the light that illumes the ground within. They took the curves of risk with two wheels hanging over the abyss. The catalogue is Homeric with those who did not come back, from George Leigh Mallory to Amelia Earhart, Ned Gillette, murdered on a glacier in Pakistan, and Doug Gordon, drowned while attempting a first descent of the Tsangpo Gorge in Tibet.

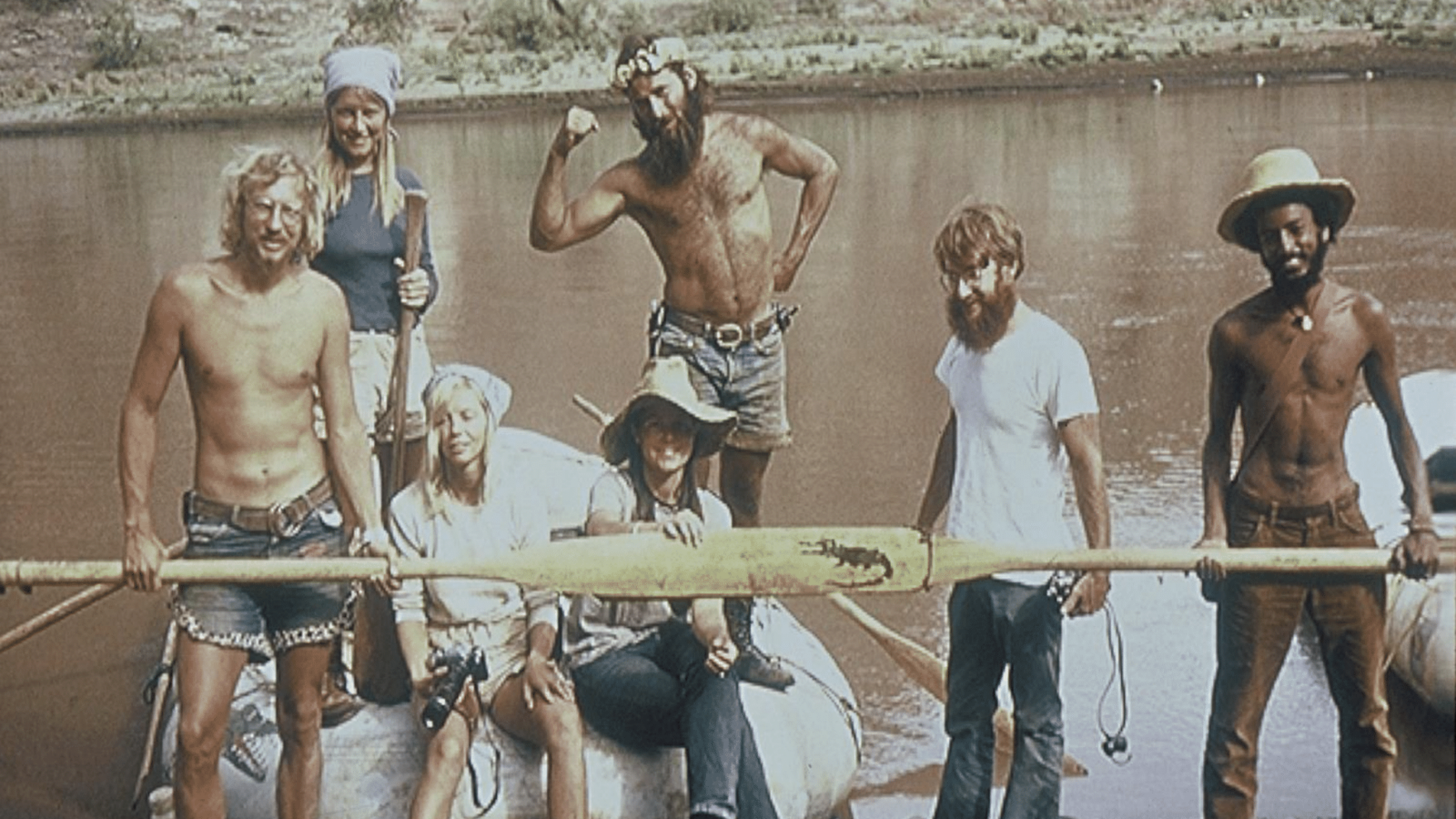

Like all, these adventures needed to be financed. Some used the glossy pretexts of flag planting or coloring in the map and found patrons; others paid their way as journalists, photographers, filmmakers, or shills for commercial products or services. And some had the family pocketbook to underwrite the passion for adventure. One of the first of this class most certainly was the pipe-smoking Englishman Samuel Baker, who spent the early 1860s on a stylish self-financed expedition exploring the watersheds of Abyssinia, camping on Persian rugs beneath double-lined umbrellas as hyenas whooped nearby; a little over a century later New Jersey native and self-styled adventurer Joel Fogel financed a first raft descent of the crocodiled lower Omo in Ethiopia with family monies. Not long after the media fawned over the various self-financed balloon adventures of dough-boys Richard Branson and Steve Fossett.

In early readings of these accounts, I sought to unpack the minds of the men and women who unsuccessfully resisted the temptation to leave the safe harbor, who became inexorably caught in the spiraling steel coils of exploration. Many held a keen conviction that humankind has become too remote from its beginnings, too remote from Nature, too remote from the innocent landscapes that lie within us. The adventures they undertook offered a chance to pluck at the strings of simplicity again, to strip the veneer of dockside worldliness and sail to some more primitive, if more demanding, state of grace, and though the world is sometimes better for the discoveries made in their bold forays, sometimes their searches proved folly, and they didn’t come back.

I once sailed by rubber boat down the Grand Canyon of Asia Minor, the Kemer Khan of Turkey’s Adiyaman Plateau, a spectacularly striated gorge of sedimentary and volcanic rock through which the upper Euphrates cut and purled for tens of thousands of years. It was such a stunning passage; it hurt my eyes and stole my breath away. Yet, when a few years later I planned to return with friends, I was shocked to discover this vault of history, the Grand Canyon of the Euphrates, had been dammed in a styptic blink, when nobody was looking, and the river flowed no more.

In 1770, the Scottish explorer James Bruce, in his search for the source of the Nile, came across the 150-foot-high Tissisat Falls in Ethiopia. He described it thusly:

“The river . . . fell in one sheet of water, without any interval, above half an English mile in breadth, with a force and a noise that was truly terrible, and which stunned and made me, for a time, perfectly dizzy. A thick fume, or haze, covered the fall all around, and hung over the course of the stream both above and below, marking its track, though the water was not seen. . .. It was a most magnificent sight, that ages, added to the greatest length of human life, would not deface or eradicate from my memory.”

Yet when I scrambled to this magnificence last year, a thin ribbon of water scraped down the cheek of a dark cliff. The immense cascade was gone, 90 percent diverted into a power scheme built by Chinese and Serbian contractors, erected without knowledge or critique from the rest of the world. The river was redeposited a few hundred yards downstream after pouring through penstocks and turbines, but it had left the great falls bald and sallow.

In 1989 I rafted the Amu-Darya that flows from Kyrgyzstan into Uzbekistan, ending in the Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest freshwater lake in the world. Now it is but a puddle, with scores of huge iron fishing trawlers tipped and partially buried in the surrounding desert, as though tossed miles inland by a massive tidal wave, a ship cemetery with no water in sight. The once free-flowing rivers that fed the Aral were siphoned to irrigate new lands and produce higher cotton yields. The same story played with the Jordan River, which feeds the Dead Sea, now shrunk to a third the surface area of a half a century ago. An Israeli resort I visited after navigating the upper river had fallen into a sink hole and was now too far from the water to walk.

This has been a subtheme to my travels and explorations over the past 50 years. So often I would stumble to spectacle so bravura, it would speed the blood and validate existence, but then upon return discover it was less so, or gone, because of non-sustainable commercial concerns set to exploit the earth. There is no waterway on the planet uncoveted for diversion or damming; there is no forest that is not lusted over for felling and development. It is a paradoxical and pestilential notion that the places we wish to remain protected and wild cannot become so unless visited and appreciated.

Over the decades, I witnessed many special places preserved and many lost like snowflakes in the sea. The critical vector in survival or demise was more often than not the number of visitors who trekked the landscape or floated the river and were touched deeply by their unique beauty and keening spirit. When such a space became threatened, there was a constituency for whom the place was personal, a collective force ready to lend energy, monies, and time to preservation. The Colorado still dances through the Grand Canyon largely because those who rafted this cathedral rallied against a proposed dam. The Tatshenshini, a river I pioneered with Sobek colleagues in the 70s, runs through one of the wildest and most inaccessible corridors in North America, through the three-mile-high St. Elias range, and is host to more grizzly bears and bald eagles than anywhere in the world. Nobody lives here; there is no evidence of man. It belongs to wildlife, wildflowers and wildness. The only intrusions are from the occasional rafters who float down the river during the summer months. Yet, when a giant open pit copper mine was proposed in the British Columbia section of the river, it was in such an obscure location the backers never expected opposition. But the rafters saw what was happening, and discovered that the mine, besides scarring the impeccable face of a wild place, would leak sulfuric acid into the watertable, which might poison the salmon, and as part of the food chain, then the eagles and bears who ate them. It was the rafters who grew incensed with this arcane project, and who built a grassroots movement to stop the project. They brought the issue to the pages of National Geographic, Life, Sierra, Audubon, The New York Times, and millions now saw the rare and special beauty that had been the privilege of a few rafters. Finally, the plug was pulled, and the region was declared an international park, due in no small part to the adventurer travelers who passed through, were affected by what they saw, and chose to act. Culturally intact Dyak villages in Borneo and throughout the tropics sustain because visitors who witnessed their magic made public battle against timber and oil companies otherwise poised with bulldozers.

Yet in my sleep there is sometimes a lament that falls drop by drop upon my heart. I am haunted by the losses and question if I could have done more to entice people to come and see. In the 1980s, I explored the Alas Basin in Sumatra, running through the largest orangutan reserve in the world. Timber poaching has reduced the once luxurious habitat to a scrawny shadow, and the “men of the forest” are on the brink of extinction. In the late 1970s, I led the first descent of Chile’s Rio Bio-Bio, a tumbling gem that offered up some of the finest whitewater in the world. I tried to persuade as many folks as possible to come glide this limpid course, but not enough, as a local power company rolled over resistance and broke the wild water with a series of dams.

In 1981, I joined President Kenneth Kaunda at a function in Lusaka to help save the last of the black rhinos of Zambia. I pledged to motivate more to experience and engage, but never really made good on the promise. When I returned in 1983, all the rhinos were gone.

A recent census estimates the lion population in Africa has decreased 95 percent since the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Luangwa Valley was home to 100,000 elephants, largest concentration in the world. Today, because of poaching, an estimated 15,000 remain. In Madagascar, 90 percent of the forests are gone. Scientists warn we are in the middle of a firestorm of species reduction, a mass extinction event. Between 1970 and 2020, the planet lost 70 percent of its populations of wild mammals, fish, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Today, roughly one million species are threatened with extinction.

If the source rivers of the Okavango Delta in Angola are dammed, diverted, or developed, as some have proposed, one of the richest wildlife basins in the world could become bankrupt. And as we gaze about the world it is not just trees, rivers, and animals vanishing. The Dead Sea is drying up; variegated coral reefs are bleaching; glaciers are retreating. There is no Planet B.

Not the only one, but a bona fide solution to saving the extraordinary, but sometimes distant, natural assets of our world is to hearten enough people to see and tap and be tapped, as then the concept becomes real and personal, not pedantic, and the value of wonder becomes patent. It is the realization of the 19th Century German philosopher, G.W.F. Hegel’s declaration of humanity’s most advanced thought, the idea that recognizes itself in all things.

I’ve spent a career designing and conducting adventures with purpose, travel that is expectantly meaningful and hopeful. But the graveyard of my own sacred places gone speaks to regrets and quests not fulfilled.

So, this book is an invitation, a summons to come and hear the raw, deep voices of nature and behold architecture supported by the brilliant beams of rainbows. By making that step beyond the equipoise of provisional comfort there is the chance to be swept away by glorious displays of flocks and herds, to be baptized into the marvels of the natural life. And then I hope when the time comes for volunteers to save what they have seen, hands and voices will rise to the sky.

Excerpted from The Art of Living Dangerously: Tales from Modern Adventure Travel by Richard Bangs, published by Lyons Press, November 7, 2023