This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

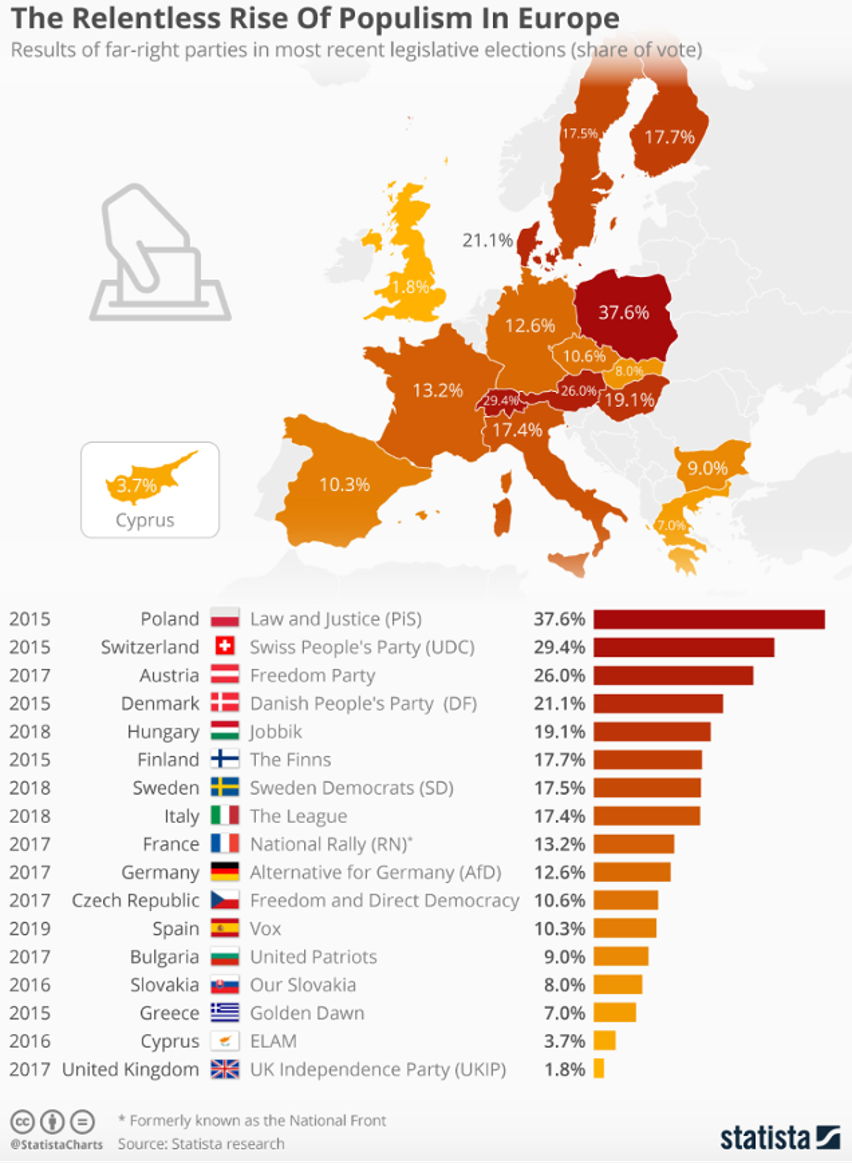

Ever since roughly 2015, much has been written about populism. The catalyst for this was three political events, all occurring within months of each other. First, there was the rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the presidential primaries of 2015—2016. Each in his own way seemed to speak—one from the political left and one from the political right—to the concerns of working-class Americans who felt marginalized by globalization and what they perceived as the misrule of social and economic elites. Sanders addressed this by calling for an ambitious program of redistributive economic policies to level a playing field which had long been uneven. Trump’s argument, too, was partially economic, embracing protectionist trade policies and hostility to NAFTA. He was also—rhetorically, at least (his policies in office would prove another matter) more sympathetic to the existing welfare state than many Republican candidates of the past. But his populism was tinged with racist and xenophobic overtones, which both fueled his political ascent and arguably poisoned the well of our public discourse in ways from which we have not yet recovered. Largely because of Trump, much of the discourse around populism was primed to view the phenomenon as, on the whole, a negative influence—crude, anti-intellectual, and even racist. This view was seemingly confirmed in the months before the presidential election, when voters in the UK chose to leave the European Union. This move was seen by many as motivated by reaction to high levels of immigration and by hostility towards the bureaucratic elite running the EU. Widespread fear of the potential economic and political ramifications of the Brexit vote meant that it, too, would do no favors for populism’s reputation, at least among those not part of the demographic which had already proven receptive to a populist message. Then there was the rise in populist far-right parties throughout Europe, reflected in the figure below. This, too, has cast populism in a negative light, and helped it become, for many, synonymous with far-right politics in general.

Populism, then, is a word which has become all but synonymous with only its worst aspects. It is easy to forget that, freed of its contemporary baggage, populism can mean simply standing with the socioeconomically marginalized, prioritizing their concerns over the interests of the powerful. The trouble we have recently seen is the wedding of populist rhetoric to policies which often favor the very elites the faux-populist rails against—and which disadvantage the dispossessed. But just because the populist idiom can be vulnerable to corruption does not mean it should be ceded to its worst practitioners. Indeed, public health owes much to populism, to a defense of common interests against the prerogatives of the powerful elite. A classic example is smoking. For a long time, cigarette companies monopolized public opinion about their product—a product which caused tremendous harm to the health of populations. These companies used slick advertising to sustain an image of smoking as glamorous, even healthy. When it became clear, through the 1964 US Surgeon General’s report, that smoking was, in fact, deadly, public health found itself in the position of the populist, working against corporate interests to stand up for the wellbeing of the less powerful.

Public health has also historically been interlinked with populist reform movements, notably those of the Progressive Era, in which reformers stood against entrenched interests to argue for worker protections and better living conditions in cities. As public health has deepened its focus on improving the material conditions of people’s lives as a means of supporting population health, it remains aligned with the classic populist position, arguing on behalf of the marginalized, often facing pushback from powerful interests who benefit from a broken status quo. Given this history, it strikes me as premature and counterproductive to let populism be defined solely by its post-2015 character. This is particularly true after the experience of COVID-19. The polarization of seemingly every aspect of the pandemic has resulted in, for many, an identification of public health with a caricature of finger-wagging elites in media, government, and the academy. This has eroded the trust on which we rely to effectively engage with the public and promote health. With this in mind, I would argue that now is the time for a public health which has reengaged with its populist roots.

What would a populist public health look like?

First, it would be, at core, about people. There is much about the work of public health that is compelling, and that can distract us from this core focus. The development of ideas, the pursuit of science, the raising and management of funds, the implementation of solutions—all this is part of our work, and all this is to the good. But we must never forget that these are meant to serve our central aim: improving the health of populations—of people. This work should always be our core focus.

Second, a populist public health is one that does not shy away from critiquing power structures the keep in place a status quo that is harmful to health. This is not to say, of course, that we should pick fights. Nor does it mean we should attempt to dismantle (as opposed to reform) systems just because they do not always produce optimal outcomes. We must simply engage with the reality that the conditions that shape health are often defined by opposing interests. When one of these interests is a powerful entity acting in ways that undermine health, and the other is a less powerful entity whose health is being threatened, we should not equivocate about whose side we are on. This gives us a perspective with which to pursue reform through reason, respecting, always, the basic societal structures that allow us to air disagreement in a context of civility. Along these lines, we should also work to ensure the partisan divides of the moment do not cloud our view of who, in fact, stands on the side of health and who does not. The emotions of the moment make it tempting to feel that anyone who is part of our political in-group is beyond critique and that anyone in a political out-group is indisputably aligned against our interests. We need to question these assumptions if we are to maintain an accurate view of who really has the best interests of health at heart.

Finally, pursuing a populist public health requires us to rethink our reflexive wariness of populism in general, to advance a more constructive vision of it. There is a reason populism has long been a potent political force—at its best, it speaks to the real needs of people, particularly those who have found themselves voiceless in the public debate. It is even worth revisiting more recent examples of populism, to ask ourselves if, beneath its darker elements, there were any legitimate grievances to which it spoke. This reflects another core motivation for pursuing a populist public health—if we do not address such grievances, others will, who may not be acting in good faith with an eye towards shaping a better world. I have found myself haunted by the title of a 2019 piece by David Frum in The Atlantic, “If Liberals Won’t Enforce Borders, Fascists Will.” It argues for a humane, pragmatic border policy as a means of forestalling a more xenophobic, abusive approach to the issue by those who would co-opt it for destructive political ends. The same goes for populism. A healthy populism can do much to create a healthier world. An unhealthy populism can actively make the world sicker, by dividing people and empowering the kind of political figures and movements that do no favors for the work of public health.

At core, public health’s mission is to care for the health of populations, with particular concern for the marginalized and vulnerable. Throughout our history, we have pursued this mission by aligning ourselves with the interests of these groups when they faced challenges. If we are indeed in a populist moment, we should not let the moment be defined by those who would use the appearance of populism to mask polices that would harm our constituencies. A populist public health can step into this breach, to advance a vision of a better world by speaking to the needs of those who stand to inherit our success or failure in creating it. At the same time, we can work to build bridges between those with power and those with less. Rather than advance a divisive populism, we can promote a populism that helps societies better cohere towards the common good. In a moment with much at stake for health, by rediscovering our populist roots, public health can become an even more effective force for good.