If I could distill my entire life into one moment, into one still image, it is this: three women in dark wool coats wait, arms linked, in a barren yard. They are exhausted. They’ve got dust on their shoes. They stand in a long line. The three women are my mother, my sister Magda, and me. This is our last moment together. We don’t know that. We refuse to consider it. Or we are too weary even to speculate about what is ahead.

This moment is a threshold into the major losses of my life. For seven decades I have returned again and again to this image of the three of us. I have studied it as though with enough scrutiny I can recover something precious. As though I can regain the life that precedes this moment, the life that precedes loss. As if there is such a thing.

I have returned so that I can rest a little longer in this time when our arms are joined and we belong to one another. I see our sloped shoulders. The dust holding to the bottoms of our coats. My mother. My sister. Me

1980

THE letter was an invitation to address six hundred chaplains at a workshop in a month. In any other circumstance, I would have accepted, would have been honoured and humbled to be of use. Because of my clinical experience and my success in treating active-duty personnel and combat veterans, I had been asked a number of times to speak to larger military audiences and had always felt that it was my moral obligation—as a former prisoner of war, as a person liberated by US soldiers—to do so. But this particular workshop was scheduled to meet in Germany. And not just anywhere in Germany. In Berchtesgaden. Hitler’s former retreat in the mountains of Bavaria.

When I tell Béla [her husband] that I have decided to decline the invitation, he grabs my shoulder. “If you don’t go to Germany,” he says, “then Hitler won the war.”

It’s not what I want to hear. I feel like I’ve been suckerpunched. But I have to concede that he’s right about one thing: It’s easier to hold someone or something else responsible for your pain than to take responsibility for ending your own victimhood. Most of us want a dictator—albeit a benevolent one—so we can pass the buck, so we can say, “You made me do that. It’s not my fault.”

And that is why Béla tells me that if I don’t go to Berchtesgaden, then Hitler has won. He means that I am sitting on a seesaw with my past. As long as I can put Hitler, or Mengele, or the gaping mouth of my loss on the opposite seat, then I am somehow justified, I always have an excuse.

That’s why I’m anxious. That’s why I’m sad. That’s why I can’t risk going to Germany. It’s not that I’m wrong to feel anxious and sad and afraid. It’s not that there isn’t real trauma at the core of my life. And it’s not that Hitler and Mengele and every other perpetrator of violence or cruelty shouldn’t be held accountable for the harm they cause. But if I stay on the seesaw, I am holding the past responsible for what I choose to do now.

Long ago, Mengele’s finger did point me to my fate. He chose for my mother to die, he chose for Magda and me to live. At every selection line, the stakes were life and death, the choice was never mine to make.

It has been thirty-five years since I left hell. The panic attacks come at any time of day or night, they can subsume me as easily in my own living room as in Hitler’s old bunker, because my panic isn’t the result of purely external triggers. It is an expression of the memories and fears that live inside. If I keep myself in exile from a particular part of the globe, I am really saying that I want to exile the part of myself that is afraid. Maybe there is something I can learn by getting closer to that part.

A month later, when Béla and I are on a train from Berlin to Berchtesgaden, I feel like the least credible person, the last person on Earth qualified to talk about hope and forgiveness. When I close my eyes, I hear the sound of my nightmares, the constant turning of wheel against track.

We share the train compartment with a German couple about our age. They are pleasant, they offer us some of the pastries they’ve brought, the woman compliments me on my outfit. Where were they during the war? Were they Hitler Youth? Do they think about the past now, or are they in denial, as I was for so many years?

The dread in me turns to something else, a fiery and jagged feeling, fury. I remember Magda’s rage: After the war, I’m going to kill a German mother. She couldn’t erase our loss, but she could flip it on its head, she could retaliate. At times I shared her desire for confrontation, but not her desire for revenge. My devastation manifested as a suicidal urge, not a homicidal one. But now anger collects in me, a gale-force fury, it gathers strength and speed. I am sitting inches away from people who might be my former oppressors. I am afraid of what I might do.

“Béla,” I whisper, “I think I’ve come far enough. I want to go home.” “You’ve been afraid before,” he says. “Welcome it, welcome it.” Béla is reminding me of what I believe too: This is the work of healing. You deny what hurts, what you fear. You avoid it at all costs. Then you find a way to welcome and embrace what you’re most afraid of. And then you can finally let it go.

We arrive in Berchtesgaden and take a shuttle van to the Hotel zum Türken, which is now a museum as well as a hotel. The hotel is like a time machine, an anachronism. The rooms are still appointed as they were in the 1930s and 1940s, with thick Persian rugs and no telephones. Béla and I are assigned to the room that Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, slept in, with the same bed, the same mirror and dresser and nightstand that once were his. I stand in the doorway of the room, I feel my inner peace shatter. What does it mean that I am standing here now?

I grab for the bedpost to keep from falling to my knees. Béla turns back to me. He winks, he bursts into song. It’s . . . springtime for Hitler, and Germany! he sings. It’s from Mel Brooks’s The Producers. Deutschland is happy and gay! He does a tap-dance routine in front of the window, he holds a pretend cane in his hands

I have to get away. I head out alone for a walk.

“Tempora mutantur, et nos mutamur in illis,” I say to the chaplains when I give my keynote address the next morning. It’s a Latin phrase I learned as a girl. “Times are changing and we are changing with them. We are always in the process of becoming.” I ask them to travel back with me 40 years, to the same mountain village where we sit right now, maybe to this very room, when 15 highly educated people contemplated how many of their fellow humans they could incinerate in an oven at one time.

“In human history, there is war,” I say. “There is cruelty, there is violence, there is hate. But never in the history of humankind has there ever been a more scientific and systematic annihilation of people. I survived Hitler’s horrific death camps. Last night I slept in Joseph Goebbels’s bed. People ask me, how did you learn to overcome the past? Overcome? Overcome? I haven’t overcome anything. Every beating, bombing, and selection line, every death, every column of smoke pushing skyward, every moment of terror when I thought it was the end—these live on in me, in my memories and my nightmares. The past isn’t gone. It isn’t transcended or excised. It lives on in me. But so does the perspective it has afforded me: that I lived to see liberation because I kept hope alive in my heart. That I lived to see freedom because I learned to forgive.”

The chaplains rise to their feet. They shower me in warm applause. I stand in the light on the stage, thinking that I will never feel so elated, so free. I don’t know that forgiving Hitler isn’t the hardest thing I’ll ever do. The hardest person to forgive is someone I’ve still to confront: myself

Our last night in Berchtesgaden, I can’t sleep. Lying awake in Goebbels’s bed, I realize that I need to perform the rite of grief that has eluded me all my life. I decide to return to Auschwitz.

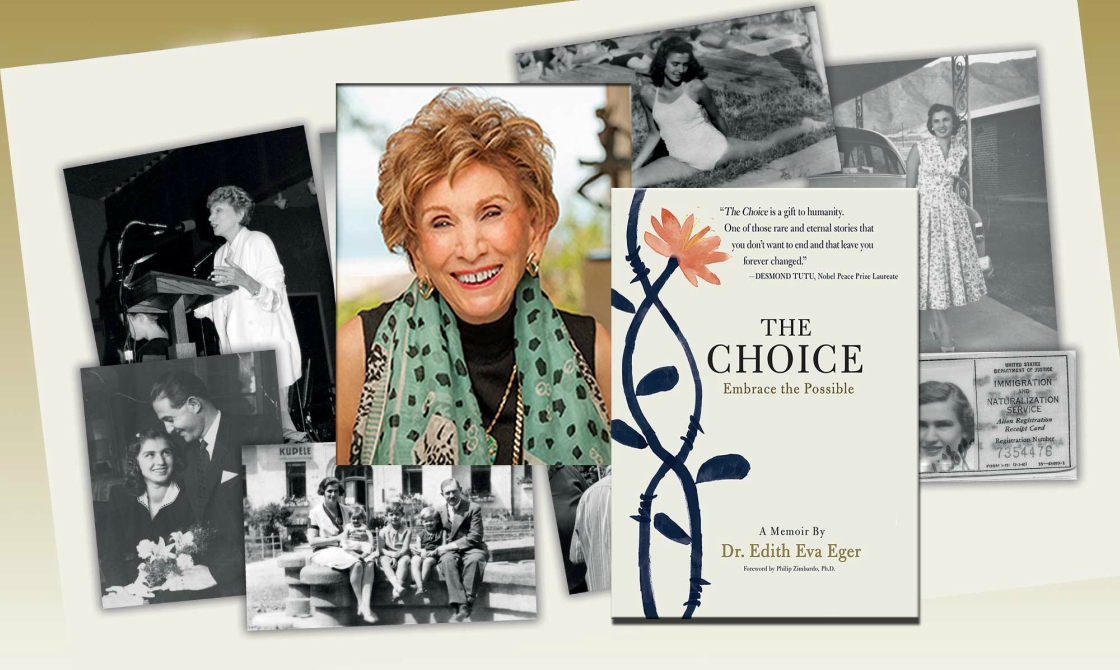

Dr. Edith Eger’s book, THE CHOICE (Scribner, September 5, 2017) is more than a memoir. It is a remarkable personal account of surviving the Holocaust and overcoming its ghosts of anger, shame, and guilt. It is a moving testament to those she has helped heal—often using the life lessons she learned in Auschwitz. Her story and those of her patients show how we can be imprisoned within our own minds—and how to find the key to freedom.