This article was co-authored with Michael Watkins.

The COVID-19 crisis has challenged us to adapt our behaviors and routines to a wrenching new reality. But just as we are coming through the initial shock and starting to settle into new routines, we are about to enter a new stage – a yet more challenging one. For an indeterminate period of time, we will be expected to do our work much like before, while balancing a highly stressful set of competing priorities, and some degree of continuing social isolation. The adrenaline rush that propelled us up to now will start to subside, just as this challenging new reality sets in.

To illustrate, consider this real case. You are a single parent of three, working for a multinational company. Your children have been engaging in remote learning for a few weeks already. You have been trying – and failing – to maintain your normal work hours from home, while overseeing your children’s work, and keeping them fed, fit and safe. Your employer may have been understanding up to now, allowing you unusual flexibility during those first few weeks. You also were able to call in some favors and organize short-term support. But now, you’re not making the hours, your project deadlines haven’t moved and your boss is becoming less tolerant. Next time you’re on a videoconference call and one of your children storms in to ask you whether you can fix them a snack, your colleagues don’t find it as cute. Though they don’t say it, the message is clear: you should have that under control by now. Knowing that this situation is not going away any time soon, how do you make it through the next stage without reaching burnout?

While it’s never going to be easy, the good news is that, if you understand what you are dealing with and have the right mindset and tools to handle it, you can master this next stage and survive, perhaps even thrive, until the crisis is over. In the process, you may even learn some coping skills that will serve you well beyond the crisis.

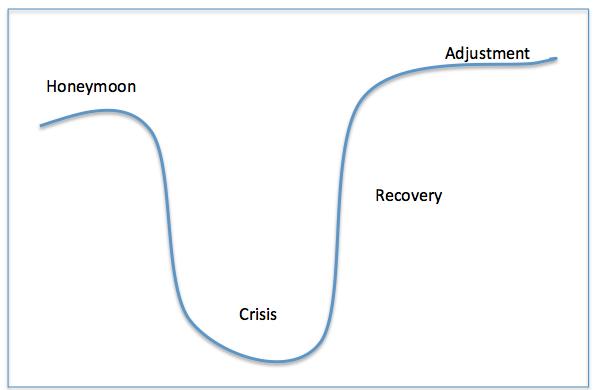

The starting point is to recognize that the Coronavirus pandemic has launched everyone on a journey that will progress through predictable stages of adjustment. The model we are drawing on was developed to describe the way people go through culture shock and eventually adjust after moving to new countries. This cultural adjustment progresses through four stages.

First comes the honeymoon stage, which can last anywhere from a few days to weeks or even months. When you first move to a new location, you are fascinated by your new environment and culture, excited about the possibilities, and eager to discover and experience everything.

After a few weeks or months in a new place, you are no longer a tourist nor are you regarded as one. Routine sets in and with it, disillusionment. You miss your old life. Things start to go wrong, and every day is a struggle. You enter the crisis stage and struggle.

If you are like most people, eventually you transition into the recovery stage, which feels like a breakthrough, because suddenly things start to make sense. You begin to feel comfortable and learn how to function effectively in your new environment: you get around without getting lost, develop new routines, and get things done. Things that previously seemed unbearable, bother you less.

The final stage of the process is adjustment, where you accept reality and begin to feel at home. You are able to function, live and work with confidence and ease in your new environment. While you may still feel strained sometimes, you are not in a state of constant anxiety like in the crisis stage.

These stages of cross-cultural adjustment are illustrated using a U-curve diagram of how wellbeing evolves over time:

Source: UC Berkeley – https://internationaloffice.berkeley.edu/living/cultural

This model of adjustment can be applied, albeit in a somewhat modified form, to the transitions we are experiencing now as a result of COVID-19 shock we have experienced. It can offer us insights that can help us to balancethe competing pressures of work and family though the remainder of the crisis.

Even if it doesn’t feel like one, the stage in which we have been up until now is a sort of honeymoon – where everything is new and surreal, we are in unsustainable state of overdrive, and we have been allowed a grace period to settle in.

Now, we are about to enter into the crisis stage, where we realize that the new reality is going to be with us for a while, and we have to learn to deal with it for the longer term. If we don’t understand and prepare for this new stage, we could end up overwhelmed, discouraged, perhaps even depressed when there is no end in sight. If we adopt the right mindset and do the right things, however, we will feel much more in control and will be able to cope much more effectively.

For the single parent we described above, this means anticipating the challenges of this new stage of adjustment and organizing coping resources and structures that will be available longer-term. Depending on the specific circumstances, this may mean, for example, negotiating a more flexible daily work schedule (and realistic commitments for deliverables) which accommodates children’s’ remote learning schedules. It may mean sitting down as a family and agreeing on to on a fair division of household tasks, on that includes older siblings taking on some of the work of supervising younger ones. It may also mean researching and organizing resources that keep the children busy – productively and creatively – while the parent has to work. This could include online language lessons, arts and crafts projects, drawing classes or other age-appropriate activities that match preferences. Last but not least, it may mean asking for support from the other parent or a trusted friend. This is just the right time to ask for favors and to create mutual support agreements.

Adjustment to a major shock is never an easy process. However, knowing that we are transitioning from one stage of adjustment to the next allows us to anticipate the challenges and to prepare for what’s coming. Likewise, having realistic expectations helps us to be more accepting of the situation and not to exhaust ourselves in pointless resistance. It also should be reassuring to know that this stage eventually will end, and we will move on to the recovery stage and eventually to adjustment to the ‘new normal’.

Finally, as with all significant changes we experience, it helps to have a ‘growth’ mindset and not to dwell too much on the (real and significant) losses. Grieving is a part of the process of adjustment, but so is growth, if you are open to embracing it.