We stay-at-home dads are a mixed group. Some chose the role. Others had it thrust upon them by circumstance, like losing a job, and some of us, like me, made the choice circumstantially. I could have kept working, but the needs of our growing family and my wife’s career made being a stay-at-home dad the obvious choice.

Setting off into largely uncharted social territory is not often the easiest path in life, but it has its rewards and opportunities as well as its share of pitfalls. I am reining in my more melancholic tendencies here so this doesn’t end up reading like its all doom and gloom, because I realize my circumstances are more fortunate than many.

I’ve also come to appreciate I’m probably well equipped to make this particular journey because of my upbringing. My parents were open minded and progressive. My mother once said of my eldest sister, “We brought you up to challenge the status quo, and she’s been challenging ours ever since!”

When I think of my childhood and the foundation that was laid for me to move into the role of stay-at-home dad, my mother looms large. She was the temporal constant in my life. She was a feminist. She filled her empty nest with employees as her children left home. She had more invested in shaking up traditional gender roles than my father. But he supported her. I can imagine him joking about “leading from behind” on this front.

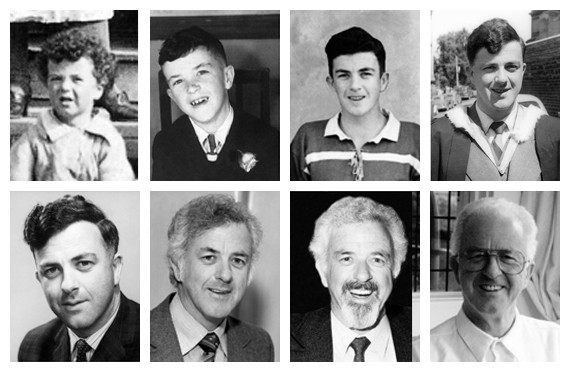

My father, John Joseph O’Hagan, moved on from this world 16 years ago.

During my lifetime he become more domestic in his habits. He learned to cook. He ironed his own shirts and folded laundry. He cleaned the toilet. He took particular delight in that.

Truth is he made more mileage out of cleaning the toilet than his labor actually warranted. I remember him demonstrating his method; wielding the toilet brush with the flourish of a virtuoso conductor. Such that he may stand accused of diluting the situation rather than cleansing it.

In 1980s New Zealand there were not many dads who did domestic things. My dad dealt with any discomfort he felt by making a joke of it. “Behind every great woman, is a greater man,” he would proclaim, turning the traditional compliment to the uber-housewife, mother, corporate spouse on its head.

He could milk sympathy for his house frau status from his mates, while wearing it as badge of honor with their wives, simultaneously, during a dinner party where he held court at the head of the table while my mother moved in and out of the kitchen.

But he would always do the dishes.

And in that jovial way he set an example. He made normal what would have to become normal in order for me to do what I do. He did much of the emotional legwork for me.

To be fair, he had his less distinguished moments too, where he would dig his toes in and go to a spot that was beyond the reaches of his normally high spirits, his affinity for reason and my, or anyone else’s, comprehension.

My father brought the left-leaning streak to my parents’ marriage. When my maternal grandfather, a rural shopkeeper, met him for the first time in the early 1950s he summed up his thoughts to my mother with the comment that he was a lovely man, even if he was a “little bit pink.”

My father’s father, Patrick, was pacifist. How strong a pacifist I am not sure. His convictions were never tested when he was of fighting age during World War I, because his skills as an electrician were declared more vital to the Empire’s cause in a factory than on the fields of Flanders where my mother’s father served.

Patrick was a tall man, who married a short woman. Her genes prevailed among their offspring until my father shot up above his older siblings. He told the story of my grandfather giving my uncle a sound beating when he signed up to serve in World War II. I guess, it was pre-hippy pacifism.

He may have got his peaceable leanings from his own father, Henry, who fought for the British Army in the Crimean War in the 1850s. I am the youngest son of a youngest son of a late life baby, so the generations spread out.

After that war Henry returned to Ireland, only to be faced with the potato famine. He emigrated to Glasgow, Scotland where he made enough of a fist of life in the Irish Catholic ghetto to get his son a vocation, and hence a ticket out of the trenches. In 1926, that son boarded a ship for New Zealand, where my father was born five years later.

So I come from a strong lineage of men who were not prepared to accept what life dealt them, men who questioned things and made bold moves. Put it that way one almost feels I should be discovering a cure for cancer or pioneering fourth generation nuclear technology.

But I am not.

I am at home, running a house and being the lead parent. I am doing something that my grandfather and great grandfather would probably never have dreamed of. But I would like to think they would approve of my choice and see how it grew out of the decisions they, and my own father, made before me.

Originally published at hdomesticus.com on June 19, 2015.

Originally published at medium.com