While studying the mountain gorillas in the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, the famously misanthropic Dian Fossey made it a personal crusade to stop poachers who were largely responsible for reducing the gorilla population to about 215 from an unknown high estimated in the thousands just decades prior. “The mountain gorilla faces a grave danger of extinction—primarily because of the encroachments of native man upon its habitat,” she wrote. Her campaign brought world attention and likely led to her own grisly murder when she was macheted six times to the head in her bed just after Christmas 1985.

Not long ago I breakfasted with Peter Guber, the producer of the 1988 biopic Gorillas in the Mist, which he cited as his proudest film in a long catalogue of features. He remembered that when he pitched the movie to Terry Semel, chairman and co-chief executive officer of Warner Bros., he was met with skepticism. Peter wanted to film the lead, Sigourney Weaver, in situ with the great apes in the Virunga Mountains for six weeks and then write the script around what transpired. “That’s backwards,” Terry asserted. “We write the script, then hire actors in gorilla suits and film on a soundstage in London. Nobody will know the difference.” Guber prevailed, and viewers were awed by the verisimilitude, and the film went on to inspire millions, fund several gorilla conservation organizations, and influence the hosting governments to make efforts to eliminate poaching.

Back in 1996, I shared dinner with Bill Gates, who had recently returned from trekking to see the mountain gorillas. He proclaimed the sight one of the wonders of the world, but he was pessimistic about the prospects. He was well-aware of the poaching issues and of the enormous population pressures that sent farmers and hunters into the gorilla habitat and thought the trend not good. At the end of a lengthy conversation that spiraled through dessert, Bill bet me $100 that within ten years the mountain gorillas would be extinct. As soon as I left the dinner party, I regretted I had not bet differently, such as 1% percent of our respective net worths.

The last census of the mountain gorilla population was in 2018, and it reported 1063 individuals, and the belief is numbers are rising. Over half the gorillas roam the protected areas of Uganda, with the remainder in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

I had long wanted to visit Uganda, not just to trek to the creatures of legend, but to see some of the landscapes that so intrigued Europeans during the “Golden Age of Exploration,” the mid-19th century when the great geographical quest was to find the source of the Nile. Many of that era stepped through or around what is today Uganda, from David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley to Sam and Florence Baker (who named Murchison Falls), to Richard Burton and John Speke. The latter duo famously disputed their respective theories on the source, with Burton claiming Lake Tanganyika and Speke the northern outlet of Lake Victoria, in today’s Uganda. Sir Richard Burton was a charismatic orator and clever linguist who spoke 29 languages, while Speke was a hunter at heart who had little stage presence and was intimidated by his former colleague. They were scheduled to debate at the geographical section of the British Association in Bath on 16 September 1864, but the day before Speke was out hunting birds at Neston Park in Wiltshire when he fell over a two-foot-high stone wall and his gun, a Lancaster breech-loader without a safety guard, went off and killed him. Accident or suicide? It will never be known, but a decade later Henry Morton Stanley surveyed both lakes and determined that Speke was right. Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, is the primary source of the Nile.

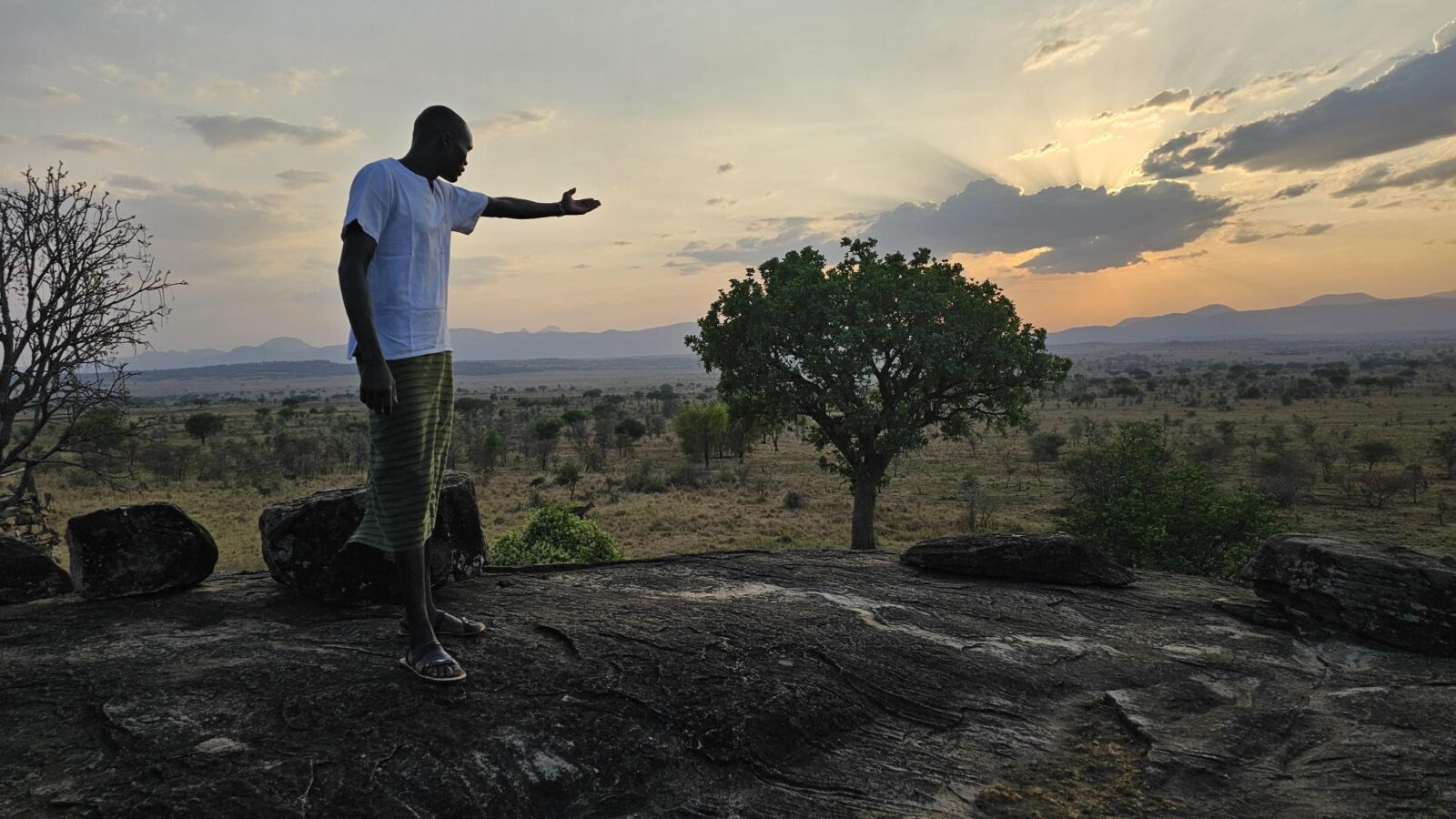

Besides its gorillas and its scruffy 19th century history of misplaced Europeans, Uganda always seemed to me to be a synecdoche for the whole of Africa. If the natural assets of the continent were poured into a small bowl, that vessel could be Uganda. It has the glaciated Ruwenzori mountains at one end, and the sprawling savannahs of Kidepo Valley on the other; it has adventures of every stripe, including rafting the upper Nile; it has over 1000 species of birds; and it features all the great wildlife of Africa and an elephantine range of cultural diversity. Winston Churchill, so impressed with its medley of environments and life, referred to Uganda as the “Pearl of Africa” in his 1908 book “My African Journey.”

And so it is I signed, along with my elder son Walker, with AGE Safaris to survey the 21st century version of an origin land inhabited by humans for at least 50,000 years.

We begin in Entebbe, mostly known for its infamous raid when an Air France flight was hijacked by supporters of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and landed here June 27, 1976. Israeli commandos stormed the plane and killed all the hijackers, with Yonatan Netanyahu, older brother to Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s sole fatality. A new airport, built by the Chinese, is soon to open, but the current terminal is busy, as we arrive during the 19th NAM summit (The Non-Aligned Movement) along with 53 heads of state.

Our first stop is to the seam where the still waters of Lake Victoria find current and the Nile River begins (there are tributaries that spill into Lake Victoria tracing from Rwanda and Burundi, but these are streams, not rivers). There is, of course, a sign designating the storied beginnings of the 4,000-mile-long river, the world’s longest, and the eucharist of life for Egypt. A grassy palisade with a monument, next to a bungee-jumping platform, claims this is where John Speke stood when he parted the leaves to witness the Nile’s first rapid, Ripon Falls, now buried beneath the glinting backwaters of the Owen Falls Dam.

We then pass through the town of Jinja, an adventure hub, to a launch site where a boatman in a small dugout ferries us between two deadly rapids to Kalagala Island and the Lemala Wildwaters Lodge. It had been highly recommended to me by a friend and former USAID director who was afire with enthusiasm for the property. His assessment was understated. My luxury banda, #10, the Aswan, perches at the wet edge of Hypoxia Rapid, one of the most extreme stretches of white water the length of the Nile. My private wooden deck, replete with elegant free-standing bathtub, hangs over the thundering currents like kudzu, while insouciant Vervet monkeys chatter and swing above. In my late teens and early twenties, I was a river guide on the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, and I found my best sleep was when camped by the side of roaring rapid. Now here, with the ultimate white noise, I slumber like a baby. And, of course, it makes sense that this insane concept was hatched by a river guide.

Lemala Wildwaters Lodge, Room # 10

In the sweet liquid light of the African morning, we head upriver to raft the rapids of the Nile. Earlier in my career I made the first descent of a section of the Blue Nile, which joins the White Nile in Khartoum to become the Nile proper, and co-authored a book on the expedition, Mystery of the Nile. And, I had led first descents of major tributaries to the Nile, the Tekeze, the Baro (which becomes the Sobat in South Sudan), and the ancient contributor, the Omo, which because of geological uplifting now ends in the inland lake, Turkana. For decades I regretted not attempting to navigate the Nile in Uganda, and now at last is the opportunity. It does not disappoint. The river here flows at about 10,000 cubic feet per second, creating huge waves and Class 3 to 5 rapids, with two portages around falls. It is just a one-day run, but it splashes back so many indulgent memories of Nile basin explorations, the crackling energy of wild water paddling, and the tohubohu of happiness.

In 1983 the Southern White Rhino was declared extinct in Uganda, poached to nothingness. Now, as a pale dawn swallows the ink of night, we make our way to the Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary, a safe haven for the re-wilded tank-like beasts. The Sanctuary, a former exotic cattle ranch, was founded in 2006 with 6 rhinos. Now there is a crash of 41, with more on the way. Perhaps the most famous is a male named Obama, whose mother was American born, while the father was birthed in Kenya, and has a birth certificate to prove it. It is an empyreal experience to walk with the second largest land mammal, with two sharp horns, and a charging speed of almost 30 miles per hour. I remember advice from the Belgian-born naturalist Jean-Pierre Hallet, who, knowing that rhinos have poor eyesight but a keen ability to detect movement, assumed the shape of a baobab when charged, and the animal veered about. I scope out a nearby acacia and when Obama stares at me I branch out my arms and stand perfectly still.

In the afternoon we make our way to Murchison Falls, described as the most powerful waterfall in the world. At the top of the falls the half-mile wide Nile forces its way through a gap in the rocks just 23-feet wide, and thunders down 141 feet, before flowing into Lake Albert. A log tossed in above the falls emerges as toothpicks at the bottom.

In addition to being soaked by the spray, I have a sense of historical vertigo. The first Europeans to witness this spectacle were Sam and Florence Baker in 1864, who were on perhaps the most romantic date ever, a 31-month long exploration of Africa in search of the source of the Nile. The 46-year-old Sam had freed the teenaged Florence from a slave auction in Bulgaria in 1858 and took her on the extended safari during which they fell in love. They married soon after returning to London in 1865, whereupon she become Lady Florence Baker, and the greatest female explorer of the era.

Murchison Falls

We take the night at the Nile Safari Lodge, a luxury solar-powered eco-retreat downstream from Murchison Falls, right on the banks of the river, which here is wide and textured like the skin of an old person’s cheek. It was along this stretch that John Huston filmed one of my favorite films, The African Queen. And the reasons become obvious while taking a boat upstream, along the way passing towers of giraffe, memories of elephant, obstinacies of buffalo, bloats of hippos, and as we approach the bottom of Murchison Falls, basks of crocodiles, hundreds of crocs, just as in the movie. The ancient Greeks called the creature kroko-drilo, “pebble-worm”–a scaly thing that shuffled and lurked in low places. The deadliest existing reptile, the man-eating Nile crocodile has always been on “Man’s worst enemies” list. It evolved 170 million years ago from the primordial soup as an efficient killing machine, so perfect it has had no need to adapt. More people are killed and eaten by crocodiles each year in Africa than by all other animals combined. Their instinct is predation, to kill any meat that floats their way, be it fish, hippo, antelope, or human. To crocs, we are just part of the food chain. Even as the water here stirs some ancient urge to shed clothes and dive in, we resist and press arms and hands by sides, and scrunch to the middle of the craft.

Stuck between a croc and a hard place.

In a jungle hollow not far below the falls Herbert, our guide, says this is where Ernest Hemingway and his wife Mary crashed in a small Cessna in 1954 while on a sightseeing tour. They spent the night stranded, rationing beer and whiskey, until the morning brought a rescue plane. But then the rescue plane crashed shortly after takeoff. The pilot kicked out a window and pulled Mary out, while Hemingway forced the door open with his head, sustaining significant injuries, including concussions, fractures and burns that affected him until his death by self-inflicted gunshot seven years later.

Next stop is at the Kidepo Valley National Park, Uganda’s most isolated on the borders of South Sudan and Kenya. We settle in at Apoka Lodge, nested in the midst of herds of zebra, buffalo, hartebeest, waterbuck and warthogs, including Bob, born at the doorstep and raised by the staff. When rangers heard of the domesticated four-year-old warthog they trucked to Apoka, blindfolded Bob, and dropped him off in the savannah 10 and half miles away, hoping to re-wild him. Seven days later he re-appeared at Apoka and makes it his home today, where he gets regular scratches from guests and staff.

Bob the resident warthog

That night, as the stars send down spears of light, we are escorted to our rooms by an armed guard, and given a key with a whistle attached, to use if confronted by something untamed. Walker can’t sleep as unknown animals surround his chalet barking, braying, snorting, and nickering throughout the night, just beyond the canvas walls. He imagines the sounds are hungry predators and curls up under the covers, whistle at hand, until a canorous chorus of birdsong fills the morning air, and he pulls back the curtains to see a dazzle of zebra parading by his deck.

The sky purples with the first thin streak of dawn as we take breakfast above the lively watering hole. Then we bluntly decant onto a road that applies an African deep tissue massage as we trundle past big game into the Narus Valley. There is a section stormy with tsetse flies, but when we arrive at the remote Loruk village, it seems a no-fly zone as the pesky insects are gone. An elder greets us and shows us around the dirt compound where some 1500 Karamojong, a Nilotic ethnic group related to the Maasai of Kenya, make home. The Karamojong are traditionally agro-pastoralists, relying on herding long-horned Ankole cattle, goats, and sheep for sustenance and cultivating crops like sorghum and millet. The wattle-and-daub homesteads, or manyattas, are roofed with what looks like witches’ hats, and inside each a small round space serves as bedroom, kitchen and living room. But simple existence doesn’t seem to have dampened spirits, as everywhere children are playing and laughing, and everyone we meet flashes big white smiles. At one point most of the young adults gather in an arc and perform the energetic Edonga jumping dance accompanied by clapping hands, stamping feet, and an ekele (a one stringed fiddle). Their bodies are adorned with beaded necklaces, bracelets, and anklets that jingle rhythmically with their movements. Our guide says the dancers with the highest jumps attract the best mates, and if a female soars, that means more cows for the dowry.

It is finally time to venture to the primary goal of this journey: to step into the misty realm of the mountain gorillas. We fly to the far southwestern corner of the country, and take rooms at Clouds Mountain Gorilla Lodge , overlooking the Virunga volcanoes, where the iconic primates, sharing 98% of our DNA, reign.

With the shuttles of dawn, we slip on nylon gators to keep safari ants from flesh, and in a cushy Land Cruiser we dust 90 minutes up into the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, a recourse that seems to have tucked itself outside of time’s crashing momentum.

Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

Walker is recovering from a work accident and doesn’t feel up to a long uphill trek at altitude in a rainforest dense and green as broccoli, so I hire a sedan chair with ten porters, several of them former poachers. The procession looks like something out of an H. Rider Haggard novel, and Walker says he feels guilty, but is soon availed of the notion when they share that the fee helps put food on the table for the families of the carriers.

The mountain gorillas don’t respect appointments, so we must find them as they roam the forests for nourishment. It can take hours to find a group, but we are fortunate and after 60 minutes hear the rustlings of the Bweza group, a family of fifteen. We are instructed to don face masks, as exposure to gorillas on these quests has the potential to transmit disease in both directions.

Behind our machete-wielding guide we wade into the uncombed tangle. Suddenly a black ball of fur flies from the top of a bamboo stalk. Then another appears, and another. With a few more steps we face two infants, looking like plush toys, tumbling and rolling about in guiltless ways; a mother patiently disciplining and grooming her charges; a teen female who is hugging one of her younger brothers; while the silverback Rurehuka (meaning peeping Tom in the local language) lounges in the middle of it all, the king on his thistle couch. They each coil and bowl and dip into a salad bowl of wild celery, leaves, nettles, and bamboo.

Our guide makes a rolling grunt-hum, “Mmmmm,” and I repeat, as he says this is gorilla language for “I’m a friendly visitor.”

Individually they stare at us with large knowing eyes, and it seems we stumbled upon a neighborhood of mirrors, or of lenses to a different time in our lives. The soft brown gaze of the apes speaks of an unfallen place and age, and for a moment there seems a kinship that transcends species barriers.

“They have 14 communication vocalizations,” our guide offers. “But we must not invoke the ones that signal aggression.” I nod, but then a few minutes later my stomach makes a loud growl, and the 600 lb. Rurehuka snaps around and makes a fast knuckle-run towards us. We were instructed not to flee during a charge, which is the overwhelming instinct, but to lower heads in supplication, which we all do. Rurehuka stops a few feet from us and snorts and farts. We look up and puffs of condensation steam from his mouth as he gives us the stink eye. After a minute, he falls back to chill on a springy bed of vegetation, dismissing my bad call for good reasons.

Now the vast forest seems motionless as in a picture, caught in a continuous Now, living in the churns of mists with neither past nor future. Then our hour is up. We are asked to depart to give the apes some peace, and we set out for the long journey home laden with a new harvest of beauty and connection.

So, why is visiting the mountain gorillas important?

For the moment, the gorilla population is stable and growing; the habitat mostly protected. Life for the surrounding communities is improving. Hope wafts the air.

But challenges remain: habitat loss, poaching, disease and human encroachment.

Mountain gorillas are a keystone species, meaning their presence ensures the health of the entire forest. Without them, the delicate balance crumbles, impacting countless other species. Their preservation is intrinsically linked to the health of the entire ecosystem, serving as a barometer of ecological integrity. As stewards of the Earth, we have a responsibility to protect and preserve biodiversity, not only for the sake of future generations but for the countless species with whom we share the planet.

And gorillas are Uganda’s green gold. Responsible tourism thrives on visitors earning distances, bringing much-needed income to local communities, and supporting vital conservation initiatives. The monies for gorilla salvation go to many good works, such as training trackers, clothing and arming antipoaching squads, snare removal, behavioral research, even inoculations. Protecting them is not just about saving lives, it’s about safeguarding livelihoods.

In the words of Dian Fossey, “When you realize the value of all life, you dwell less on what is past and concentrate more on the preservation of the future.” Let us heed her wisdom and unite in our resolve to preserve the mountain gorillas of Uganda, for they are not just a species in need of our protection; they are symbols of optimism, resilience, and the enduring power of nature’s wonders.

In the end, the most compelling reason to meet the mountain gorillas is because they inspire us. Gazing into their wise eyes, witnessing their tender family interactions, one can’t help but feel a connection. They remind us of our shared humanity, our responsibility to the planet. Saving them isn’t just about saving a species, it’s about saving a part of ourselves.

Richard’s latest book, The Art of Living Dangerously, is available now in bookstores and on-line.