In this adapted excerpt from the new book Earthly Order: How Natural Laws Define Human Life, environmental system scientist Professor Saleem H. Ali, considers how a greener lifestyle correlates with happiness at an international level.

America’s founding fathers enshrined the pursuit of happiness, alongside “life and liberty” as our ultimate quest. But let’s ponder further on this blissful term. Philosopher Bertrand Russell grappled with human well-being and the ability to thrive in his seminal book The Conquest of Happiness (published in 1930). To quote Russell: “The good life, as I conceive it, is a happy life. I do not mean that if you are good, you will be happy; I mean if you are happy you will be good.” Let’s challenge Russel’s premise a bit further and ask: can we also be happy by being good? And what is the most universal attribute of being good – could environmental consciousness be one such universally “good” attribute?

There are indeed limits to our quest for happiness. Most psychologists who have studied happiness agree that about 50 percent of our day-to-day happiness is determined by temperamental factors that are beyond our direct control. An additional 10 percent is determined by social circumstances and perhaps around 40 percent is within our control in terms of behavioral choices. It is essentially this component which the “happiness industry” has been catering to with remedies ranging from shopping-therapy to yoga. Interestingly enough, many of these remedies also correlate with ecological behavior where we are trying to connect social or even political order to some form of “earthly order.”

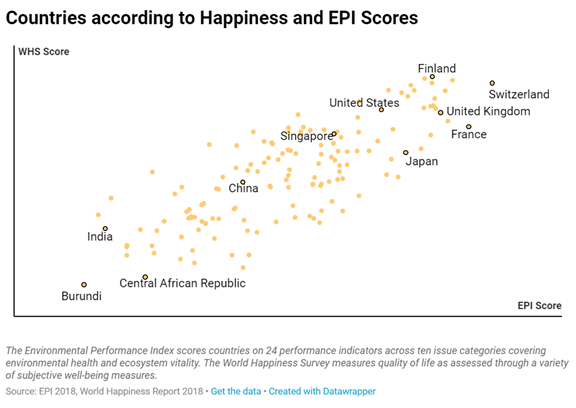

The graph below (Figure 1) shows the relationship between one measure of quality of life (the World Happiness Score, calculated annually by the United Nations) and the Environmental Performance Index at a country level. The clear relationship between quality of life and environmental performance suggests that social order has positive synergies with ecological order. Yet bringing this to the realization ofpoliticians who may still be focused on some grand security of borders approach to “world order” remains a challenge. Although using a country as a unit of analysis is always problematic, such index comparisons build on underlying governance factors for which such comparisons at country level are plausible. Also, the country-level approach helps to smoothen out data blips which may be caused by specific circumstances and exceptions.

Usually, the environmental impact of consumerism comes up in such contexts and the question arises: can money “buy happiness?” One might wonder what level of wealth is minimal for happiness and can lessons from a remote kingdom be applied to the United States? Economic psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman has estimated that for our country’s average family size and annual expenditure, an income of around $60,000 is needed to attain the monetary component of happiness. Further income is unlikely to contribute to our feeling of “happiness.” Around 65% of our population is still under this income bracket. So what do we do? Research suggests that while meeting material needs can contribute to wellbeing, such factors cannot sustain happiness. We need to have “superordinate goals’ which can link to serving some broader societal purpose. Environmental action provides such a superordinate goal for people to consider their overall contributions to society.

The World Happiness Survey, which is used to develop the indicators represented on the y-axis of the chart is now conducted by the United Nations regularly to further understand the linkages between well-being and governance as well. The study weights the ranking based on these seven components in explaining the aggregate score most effectively: a) GDP per capita as a corollary for overall economic size of country and opportunity; b) social support programs; c) healthy life expectancy; d) freedom to make life choices; e) generosity; f) perceptions of corruptions; and g) dystopia + residual. This final category has a peculiar name which needs to be understood better in the context of our reflections on political order as it is the largest explanatory factor for the top 20 countries. The methods section of the report states that “dystopia is an imaginary country that has the world’s least-happy people. The purpose in establishing Dystopia is to have a benchmark against which all countries can be favorably compared (no country performs more poorly than Dystopia) in terms of each of the six key variables, thus allowing each sub-bar to be of positive (or zero, in six instances) width. The lowest scores observed for the six key variables, therefore, characterize Dystopia.”

The need for dystopia as a category suggests the importance of benchmarking in any efforts at developing ranked orders in any categorization. We aspire for Eden (Utopia) in our lives – often linked to environmental variables — but can calibrate our wellbeing with a fictional nadir of wellbeing (Dystopia). As we better consider the underlying sense of well-being that being connected to nature provides, while also considering the negative aspects of environmental decline on well-being, this category may get further unpacked. Not only do we as individuals benefit from greening our behavior, but the really powerful message of this emerging research is also that entire nations improve in their well-being through being more in harmony with natural systems. While imminent concerns about environmental damage can also cause anxiety, the ability to act, change and contribute to improved ecological conditions quickly changes that despair to more “sustainable” gratification – both for the planet and for ourselves.