“This wasn’t supposed to happen! Tell me why this has happened!”

These are the spoken words of countless bereaved parents throughout countless years in countless languages. A never ending and always present wound in the Souls of those who have buried their children.

Parental grief is forever boundless; an ever present, deep-seated wound that has no name. There’s a reason no label has been ascribed to those who have lost a child — it is too foreign a concept, a much too chaotic form of brain freeze, an enormously frightening emotion for any language in the world to even consider naming.

Within that foreign concept lies the heart of the matter — losing a child is the most frightening, unspeakable, unresolvable and ultimately the most devastating deprivation of a lifetime. It is disorienting, unimaginable and is the most unacknowledged universal trauma of them all.

It is the very nature of this grief that makes the concept of “closure” almost laughable. Psychology tells us to look to “closure” as a way to live within this boundless grief. Finding the “certainty” we need to make things whole again is supposed to exist within this concept so easily spoken of by well-meaning friends and therapists. The need for cognitive closure (NFCC) is supposed to provide us with an ending to all ambiguity and bring us certainty. Within that certainty, we should find freedom from all the questions that live and breed in our lives as to “why” our child had to die. Problem is — most parents see their child’s death as multi-factional. It wasn’t just the child that was lost, it was the parent as well. The parents lose their way in the world and the entire premise of how the universe operates is shaken to its core. There is a natural order in life, a death order, if you will. First, it’s the grandparents, then the parents. All should pass from this world in the natural order of life events. At least, that’s what we think. But it doesn’t happen that way in “real” life. Children die and the overwhelming loss that becomes the new way of living in the world is never one for which “closure” exists. The feeling of having “lost a limb” becomes a life wound, a Soul wound that never heals.

There truly is no definition for exactly what this form of grief “feels” like. It is a wrenching sadness and a despair from which recovery cannot be found in any form of what we call “closure” except that which can, somehow, reach deep within the recesses of what we know as Spirit and start a healing process that acknowledges the fact that life isn’t fair, that we never really “get over” this kind of loss, that we keep on breathing and that children do die. Trying to accept our, and our children’s mortality, trying to accept all that has been or will be or can never be again, deciding how we will honor our child and keep them “alive” within our family, and trying to accept the fact that death is part and parcel of all life may be the key to survival for those parents who suffer endlessly with questions for which there are no answers. But there is never certainty, never total acceptance and never closure in our collective human condition that keeps us from fully accepting all these things. And, perhaps, an even larger impediment to consider can be found within the parents need to “keep and maintain” the relationship with the lost child. Holding onto the grief, many times becomes a staple in the need to maintain that relationship. As if letting go of the grief means letting go of the relationship and losing their child all over again. Maintaining the relationship within the grief experienced at the time of death can become all important to a bereaved parent. Those final moments may be all that can be “felt” because anything else — memories of the good, the bad, and everything-in-between can become tangled up with unanswerable questions and lead to the could of’s, should of’s and if only’s of having no future with the lost child. Losing a future together can be and, often is just as devastating as is the actual physical death of that child. Even thinking of closure as a possibility then becomes some foreign notion that will never be considered because it is seen as a complete loss of all relationship, past and future.

Healing from the death of a child is a lifetime journey. If there is any healing at all! And looking for “closure” does one thing and one thing only — it simply grounds you in the very thing that you are trying to heal within your very damaged and wounded Soul. I mean, life is hard stuff. It presents itself in the light of day and the dark of night in varying shades of joy and despair-all in the same day. Life is amazing. Then it’s not. It’s mundane. Then it’s horrific. You can’t out-run it any more than you can defeat it. You can’t change it without changing yourself, your environment and your very Spirit. You can deny it and try to hide from the realities of it for a while until it catches up to you, which it always does! Life can be messy and painful and joyful and filled with grief and laughter all at the same time! Don’t try to plot it on a straight path, you will lose every time!

All you can do is look within and try to accept the mortality of all things. Then decide how you will be “in this world’ and how you will honor those you love while trying to figure out how to honor yourself again. Forgetting isn’t an option. No drug, no mind-bending herb, no (as the song says) “wishing and hoping and thinking and dreaming” will take you back into that “before time.” That moment in time is forever gone. There is now only the “after time” to be dealt with and incorporated into what is remaining…and what that “remaining” stuff is, well, that’s up to the survivors to decide for themselves.

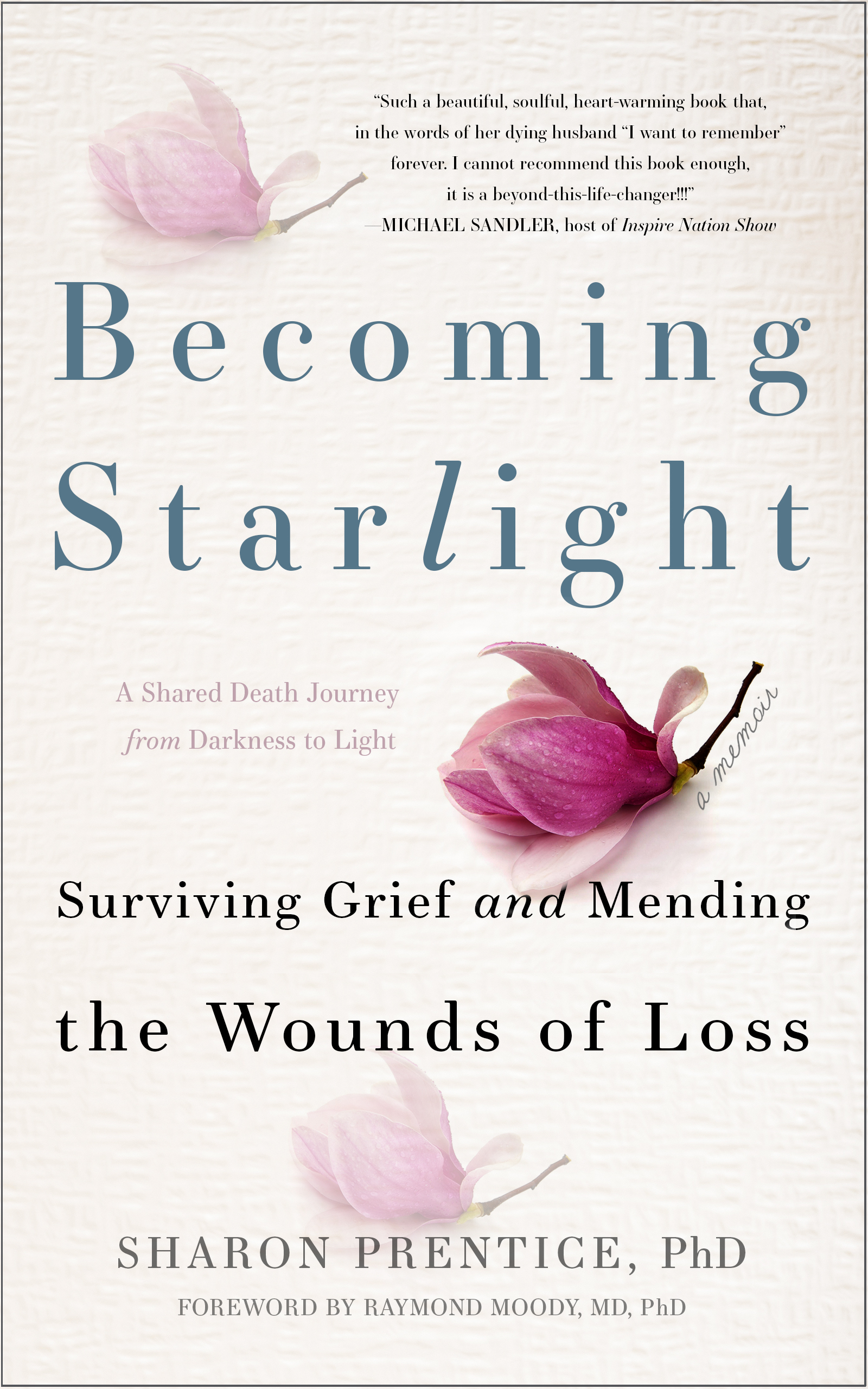

Dr. Sharon Prentice is the author of ‘Becoming Starlight: Surviving Grief and Mending the Wounds of Loss.’