Part I: Our Past:

From Eco-Earth Dwellers to Incredible Eco-Systemic Biosphere Destroyers

As Yuval Noah Harari writes in his book, Sapiens, our genus Homo (humanoids) survived for 2 million years as mid-range predators among a number of other large mammals who roamed across Africa’s open savannah. When our species, Homo sapiens (smart humanoids) came on the biological scene, nature selected for us relatively large brains (2-3% of our body weight), which consumed inordinate amounts of energy (25% of our body’s energy at rest). Living on a harsh, exposed open plain with ferocious animals lurking around every desert bush, required gladiator-like brawn; not nerdy brains, to survive. Thus, the maturation of our minds didn’t seem the smartest evolutionary strategy at the time or for 100’s of thousands of years thereafter. But then, our fate shifted and our brainpower trumped our body power in driving the extraordinary evolutionary success story for humanity that then unfolds.

As our foraging and fishing ancestors evolved, we resourced our brainpower to better sense our environment, to more carefully observe the seasons, to track animal migration patterns, to observe their success strategies, and to remember-recall-repeat for our offspring the growth and fruiting cycles of highly nutritious berries, roots, and mineral-rich greens. As our ecological knowledge grew, so did our health and our brains’ neural networks— increasing our hand-eye coordination and manual dexterity to the exquisite end of crafting tools that helped us better hunt and better access the energy-rich meat of larger predators. Clever hominids that we were, we also recognized that our chances of individual-family survival increased exponentially when we lived in communion with a larger collective. Thus, our early ancestors became highly social beings; developing structures, communications, norms, and behaviors that encouraged and enhanced the collaboration and health of the entire tribe. Dynamic and dangerous as the savannah seemed (my impression from natural history exhibits I’ve visited in different parts of the world), our earliest ancestors lived their Natura Vera (true self) also in communion with our wild cousins on different and more distant branches of yet the same phylogenic tree…and in harmony with nature. Our foraging and fishing ancestors were supremely attuned to the ecology (knowledge of their home) of the environment. They lived their lives and played their musical instruments in tune and tempo with the other living organisms in the biosphere’s symphony. This is what it meant to live in harmony- to play one’s life music in resonance with the rest of the living biosphere’s vibration.

However, as our brains, culture, and ambitions grew as a species; we began to tour the world as a solo act and forgot to mix our track down with the musical tracks of other species in tune with nature’s deeper biurnal beat. Once hominids asserted themselves on the plains with the first big game hunting tools- spears (nearly 400,000 years ago), it did not take long for our innovative ancestors (Homo sapiens) to climb to the top of the food chain (100,000 years ago)… even if we left others behind. We innovated and explored our living planet because our minds were infinitely curious and our adventurous spirit, undying. We dominated every region to which we migrated because we could, but we didn’t consider the evolutionary consequences.

Why us? We were special in that we welcomed new ideas and invited unfamiliar (literally outside the family) others among our species to contribute vision and strategy in optimizing the hunt; in refining tools and techniques for survival on the savannah! The brilliant message for us today in this narrative is that creative collaboration among a diverse group of unfamiliar others, gave Homo sapiens the evolutionary edge.

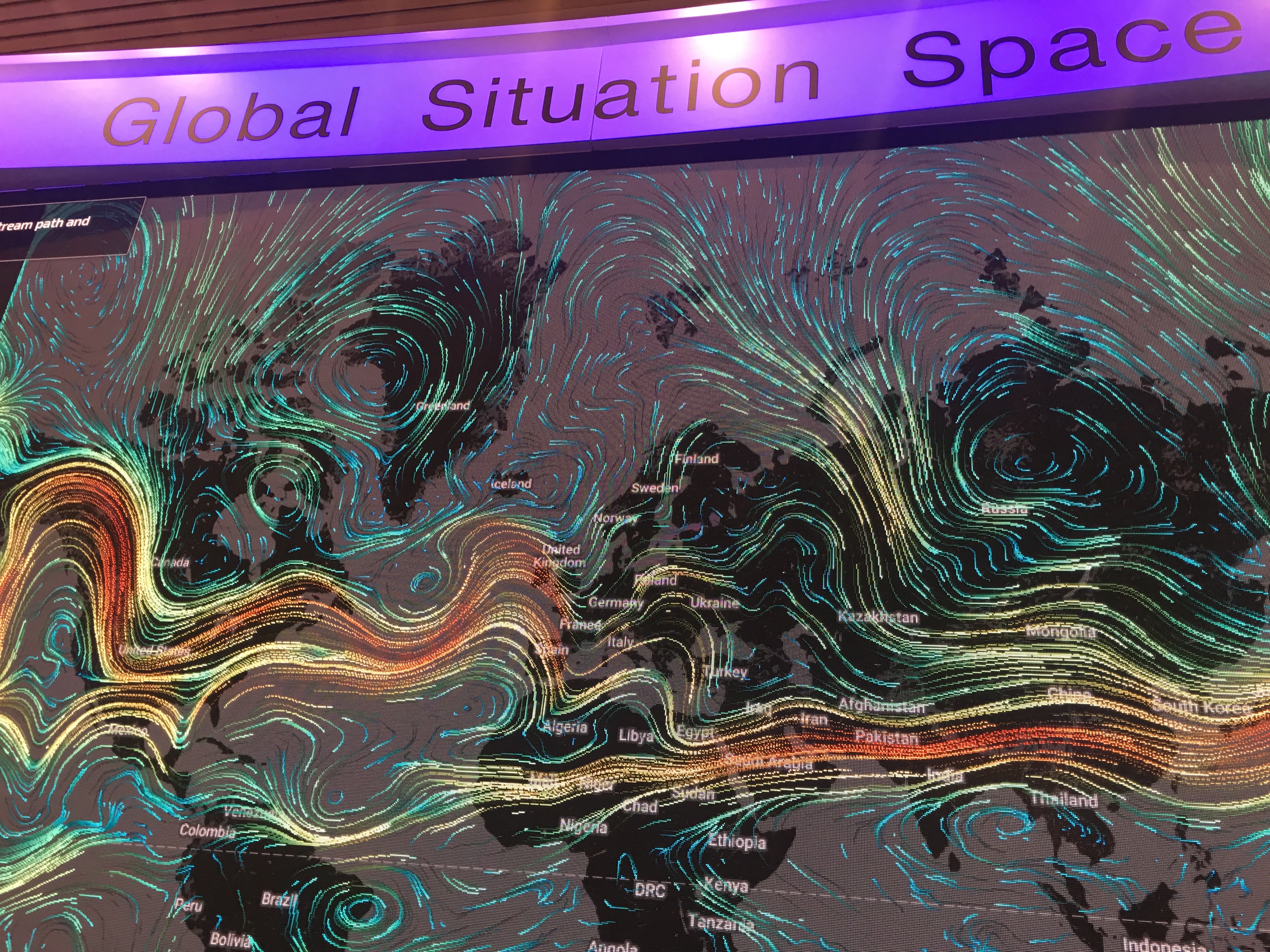

Work Group Sessions, World Economic Forum, 2019

Conversely, the most important cautionary tale for us to take away from this seminal moment in our evolutionary history during our rise at top predators (100,000 years ago) is the following. True, we reigned over the savannah and mastered Prometheus’s fire to expand our cuisine and to fuel our creative innovation. But, we also decimated the biological diversity of the entire Afro-Asian ecosystem; likely exterminating all other competing Homo groups, in the process. And, we didn’t just do it once 100,000 years ago. We repeated this behavior throughout our prehistoric history and across the continents as we migrated outside Afro-Asia and overseas. While our early ancestors invented bows, arrows, boats, lamps, clothes, pottery, and language from 70,000-30,000 years ago; they also traveled to Australia and drove 90% of the Australian mega-fauna (e.g. Diprotodons, wombats, native birds and reptiles) to extinction almost overnight -45,000 years ago. (Yuval Harari, Sapiens) Further, even as our social alliances became more intricate; our language, more complex; and our daring spirit to migrate across the Siberian land bridge into the unknown arctic, more inspiring; we still caused the extinction of 34 out of 47 genre of large mammals once we reached America’s great plains (14,000 years ago). Wholly mammoths, giant sloths, saber-toothed tigers- large mammals whom roamed the earth for nearly 30 million years were gone after only 2,000 years of exposure to Homo sapiens. (Smithsonian Natural History Museum, USA) Concurrently, as humans explored previously isolated island communities, landing on the shores of biologically rich Fiji, Madagascar, and New Zealand, we settled and caused a second wave of human-driven animal extinction that in these un-expecting island communities nearly decimated the entire native population of animals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Sadly, it seemed that from most every paleo- archeological record once we arrived to a new location not only did the biodiversity drop, but all the other native human (hominoid) populations disappeared as well, one after the other until Homo sapiens remained the last hominid standing. Dwarf-size humans from the Flores Islands were the last hominoid group to disappear from the geologic record right at the dawn of the Agricultural Revolution, 12,000 years ago (Yuval Harari, Sapiens). Thus, by the time we started to cultivate barley on the floodplains of the Fertile Crescent, rice in China, and maize in the New World; we had effectively caused the extinction of all other hominid groups, 50% of the 200 genre of large, terrestrial animals, and 100’s of species of birds, reptiles, amphibians, worldwide… let alone the other unreported, undiscovered species in the fossil record.

Prince William and Sir David Attenborough, World Economic Forum, 2019

Does this story sound familiar? Just last month at the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos 2019, the recipient of the prized Crystal Award and one of the most trusted British broadcasters in history, Sir David Attenborough (93 years old) made a similar statement about species extinction and safeguarding our planet. But he wasn’t talking about large-scale species extinctions caused by humans 100,000, 70,000, or 14,000 years ago… he was talking about an epic-scale species extinction happening right now in our lifetimes that could parallel the Crustaceous extinction of dinosaurs 65 million years ago. This third human-caused wave of extinction that 7.7 billion people now living on the planet have ridden through during the Industrial Revolution is the killer wave, the Big Kahuna. The WWF Living Planet Report (2018) somberly concludes that we have been in our lifetimes- agents and witnesses of nearly 60% loss of species abundance, worldwide. The loss of biodiversity at this magnitude and global scale is quite serious—not only to the (our) individual species but to the viability of the ecosystems within which they (we) live.

World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting 2019

We are not talking about the loss of a few cute creatures we can no longer observe on nature treks or even biological communities destroyed after a natural disaster. We are talking about the disappearance of multiple keystone species, whose absence in biological communities worldwide begins to unravel symbiotic relationships and food web partnerships, formed over millions of years. We may very well be talking about complete shut down of ecosystem services provided by nature- plants and animals we take for granted- pollination of fruits and fields, purification of water in wetlands, absorption (neutralization) of polluting atmospheric carbon dioxide… on and on. Coupled with the non-life supporting changes we have caused to our environment and climate; we are poised for the perfect storm of ecological collapse, which certainly isn’t good for our natural biosphere and can’t be good for our species inherently tied to nature, either. Whether we know it or not, nature powers our world, gives us food to eat and air to breathe, an ecological community, and a common home. Crazy as it sounds, our generation is likely the first generation to witness entire ecosystem collapse from the bleaching of the coral reefs in the Pacific to the disappearance of alpine plant communities, resident across the world’s big mountains. Many scientists, naturalists, sustainability experts, climate leaders, and passionate earth advocates have also made claim that our generation may be the last generation, as well, to turn the tide and to avoid an earth system’s tipping point into a new paradigm. David Attenborough alluded throughout his many appearances and panel discussions at WEF 2019 that we really don’t know what lies ahead. We’ve never been on the brink of ecological collapse before. There are likely many species yet undiscovered that we have lost or might soon lose, which may/may not have played an important role in the health of particular communities or provided through their biology, behavior, or chemistry keys to unlocking existing, intractable human challenges.

“We just don’t know…and we will never know… but what we do know is that our planet is alive and it connects us all. It’s maddening that we are so slow off the mark, that we prefer convenience over consequences; but the truth is human civilization is colliding with the earth’s ecological system. We can’t afford to waste any more time. We have got to now focus on practical steps to course correct our negative impact on earth. Think of the children.” David Attenborough, WEF 2019

Watch: Our Planet Nature Series (Premiering on Netflix, April 2019)

How did we become the most dangerously lethal species in all biological history?

We rose as top predators- unmatched by all other wildlife (including our closest phylogenetic cousins in the tree of life) in any and every place we lived or migrated to with extraordinary speed, scope, and scale. We rose beyond the limitations of our own evolutionary biology and unlike any other top predator in any other ecosystem before or since. The lion, the king cobra, the orca- all top predators matured into their role at an evolutionary speed and scale that allowed the rest of the prey species in the food web to guard against predatory oversteps. As natural selection continued to favor the optimization of a predator’s skill or behavior, natural selection did the same for the prey, who continually adapted new survival strategies- like camouflage, special scents, alarm calls, faster speed, agility to ever-evolving predators. Thereby, predator-prey populations maintained a rhythmic bi-modal stable dynamic, which like the hope of Nikola Tesla’s AC (alternating current) coil would continue to generate (and regenerate) symbiotic energy across the living sphere in perpetuity. Unfortunately, our species became aloof to and ignorant of such evolutionary checks, such that we subjected grasslands, coasts, mountains, and deserts time and again to human development, expansion, and economic gain with little regard for ecological return.

Indeed, there is a lesson here. Had we evolved our consciousness wisely, reflectively, graciously, slowly… with a more dominant sixth sense of stewardship for all living beings, then we might not now be waking up to our world, having suffered such biologic loss. We protect that which we love. Had we learned earlier in our rapid race to industrialize, mechanize, urbanize – advance our human civilization; the circular ecology and economy of all things, or the inherent link between our species health and the health of the planet; then we might not have acted out our global reign in the biosphere over the past 100,000 years in the same way. But now, here we are pinned up against an evolutionary wall, staring at ourselves in the mirror, anxious about the exponential (seemingly unavoidable) pace of change, questioning our future fate, and wondering how we get back to our Natura Vera—our true selves, playing our modern music in harmony with the biosphere’s larger symphony.

“When the world pushes you to your knees; you are in the perfect position to pray. And, there are a thousand ways to kneel and kiss the earth.” Rumi

Catherine Cunningham and Natural Intelligence Media is committed to awakening Natural Intelligence in the World. We produce multimedia content — books, films, and podcasts aiming to inspire you to live a happy, healthy, nature-conscious life.

Follow the World Economic Forum in Davos 2019 on Twitter via @WEF and @Davos, and join the conversation using #WEF19.

Visit our Natural Intelligence website.

Listen to our NEW Natural Intelligence Worldwide Podcast.

Special Thanks to Eurovision!!!!