Three-quarters of a century after liberation, I still have nightmares.

I suffer flashbacks. Till the day I die, I will grieve the loss of my parents, who never got to see four generations rise from the ashes of their deaths. The horror is still with me. There’s no freedom in minimizing what happened, or in trying to forget.

But remembering and honoring are very different from remaining stuck in guilt, shame, anger, resentment, or fear about the past. I can face the reality of what happened and remember that although I have lost, I’ve never stopped choosing love and hope. For me, the ability to choose, even in the midst of so much suffering and powerlessness, is the true gift that came out of my time in Auschwitz.

It may seem wrong to call anything that came out of the death camps a gift. How could anything good come from hell?

The constant fear that I’d be pulled out of the selection line or the barrack at any moment and thrown in the gas chamber, the dark smoke rising from the chimneys, a pervasive reminder of all I’d lost and stood to lose. I had no control over the senseless, excruciating circumstances. But I could focus on what I held in my mind. I could respond, not react. Auschwitz provided the opportunity to discover my inner strength and my power of choice. I learned to rely on parts of myself I would otherwise never have known were there.

We all have this capacity to choose. When nothing helpful or nourishing is coming from the outside, that is precisely the moment when we have the possibility to discover who we really are. It’s not what happens to us that matters most, it’s what we do with our experiences.

When we escape our mental prisons, we not only become free from what has held us back, but free to exercise our own free will. I first learned the difference between negative and positive freedom on liberation day at Gunskirchen in May 1945 when I was seventeen. I was lying on the muddy ground in a pile of the dead and dying when the Seventy-First Infantry arrived to free the camp.

I remember the soldiers’ eyes full of shock, bandanas tied over their faces to block out the stench of rotting flesh. In those first hours of freedom, I watched my fellow former prisoners who were capable of walking—leave through the prison gates. Moments later, they returned and sat listlessly on the damp grass or on the dirt floors of the barracks, unable to move forward.

Viktor Frankl noted the same phenomenon when Soviet forces liberated Auschwitz. We were no longer in prison, but many of us weren’t yet able, physically or mentally, to recognize our freedom. We were so eroded by disease, starvation, and trauma, we had no capacity to take responsibility for our lives. We could hardly remember how to be ourselves.

We’d finally been released from the Nazis. But we weren’t yet free.

I now recognize that the most damaging prison is in our minds, and the key is in our pocket. No matter how great our suffering or how strong the bars, it’s possible to break free from whatever’s holding us back.

It is not easy. But it is so worth it.

I don’t want people to read my story and think, “There’s no way my suffering compares to hers.” I want people to hear my story and think, “If she can do it, so can I!”

We do not change until we’re ready. Sometimes it’s a tough circumstance—perhaps a divorce, accident, illness, or death— that forces us to face up to what isn’t working and try something else. Sometimes our inner pain or unfulfilled longing gets so loud and insistent that we can’t ignore it another minute.

But readiness doesn’t come from the outside, and it can’t be rushed or forced. You’re ready when something inside shifts and you decide Until now I did that. Now I’m going to do something else.

Change is about interrupting the habits and patterns that no longer serve us. If you want to meaningfully alter your life, you don’t simply abandon a dysfunctional habit or belief; you replace it with a healthy one. You choose what you’re moving toward. You find an arrow and follow it. As you begin your journey, it’s important to reflect not only on what you’d like to be free from but on what you want to be free to do or become.

Finally, when you change your life, it isn’t to become the new you. It’s to become the real you — the one-of-a-kind diamond that will never exist again and can never be replaced. Everything that’s happened to you — all the choices you’ve made until now, all the ways you’ve tried to cope — it all matters; it’s all useful. You don’t have to throw everything out and start from scratch. Whatever you’ve done, it’s brought you this far, to this moment.

The ultimate key to freedom is to keep becoming who you truly are.

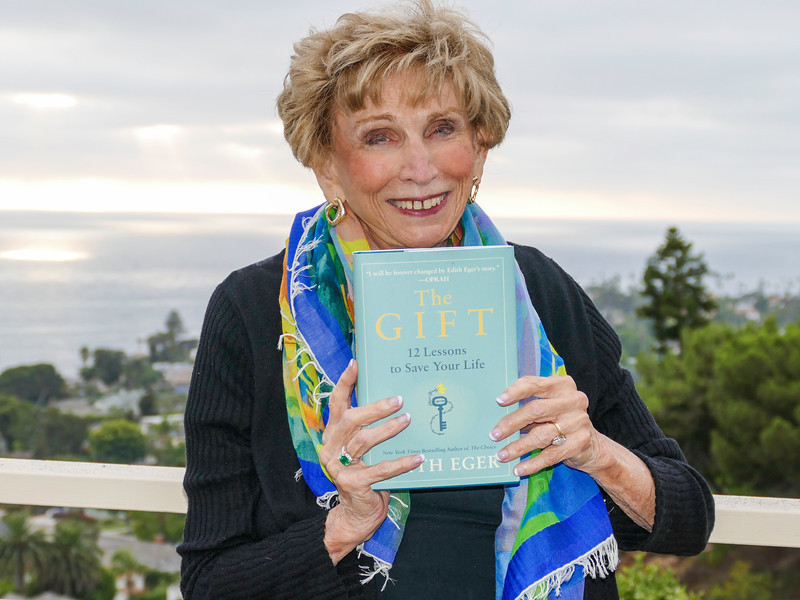

Excerpted from The Gift: 12 Lessons to Save Your Life, by Dr. Edith Eva Eger, Published 9/15/2020, Scribner.