Whether you’re cradling a warm beer at a networking event, or greeting your very first tinder date — the question you will most likely hear is the same: “So, what do you do?”.

From an early age we are taught that it’s important to figure out what we will do when we “grow up”. We also learn, through books and TV shows, that hidden identities are attached to this decision. A doctor is more trustworthy than an online gambler; a salesperson will be more chatty than an engineer; a charity worker more moral than an advertising exec. We develop these cognitive shortcuts to help us frame and predict the world around us, but they increasingly don’t tell the whole story.

Let’s take a friend of mine.

At work, she is an ‘account manager’ but she’s also learnt weaving, loves yoga and boxing and is a great life drawer. Whilst she used to enjoy her job, she has recently ended up feeling that all she seems to do is work. Staying an hour later here or there, she feels she has time for nothing else. This has started to erode her self esteem. When she goes home — even with time left in the evening — her energy is sapped. She doesn’t have time for boxing or life drawing — despite needing this revitalisation more than anything.

She is disengaged. Disengaged from work, and from her life.

In corporate terms, this ‘disengagement’ is talked about as lost productivity, low retention and high hiring costs for the employer. However job disengagement also matters profoundly for our sense of self. After all, we increasingly define ourselves by how we spend our working hours: work is no longer a separate part of who we are, it is crucial.

People now have their job title not just in their LinkedIn profile but in their Instagram bio, they post job updates on their Facebook page, and even as you get a weekend coffee you’ll see people stooped over Macbook airs, working.

This work life blend has even become aspirational. It’s cooler to “live to work” instead of to “work to live”. Flexibility and control have become our mantras: instead of maximising leisure time it is a matter of how expertly we can blend work and play. The dream is no longer to finish at 5pm, or go on longer holidays, but rather to be able to go the gym on Tuesday afternoon, or work on the beach.

Because of this importance work has on our sense of self, often when people feel alienated from the work they are doing, they don’t look into the specificsof why they feel stressed or bored, or why they feel their work lacks purpose. After all, how can they find fault in something they rely on for their identity?

Instead, a distressing cognitive dissonance can take over.

In this confusion, a new, broader existential question starts to gnaw: ‘What Am I Doing With My Life?’

We know we should be able to answer this. In the past 10 years alone we’ve seen a lot of change and opportunity, the rise of remote working, an increase in freelancers and the advent of new economies: the gig economy and even the influencer economy. We have more options of where to work, how to work and what to do for work than ever before.

We also have even more opportunities to change our path than ever before. The average ‘Millennial’ changes career 4 times within the first 10 years following graduation, and there are a plethora of opportunities to up-skill: from Coursera to Webinars to YouTube. We have opportunity to change coming out of our ears.

But there’s a problem.

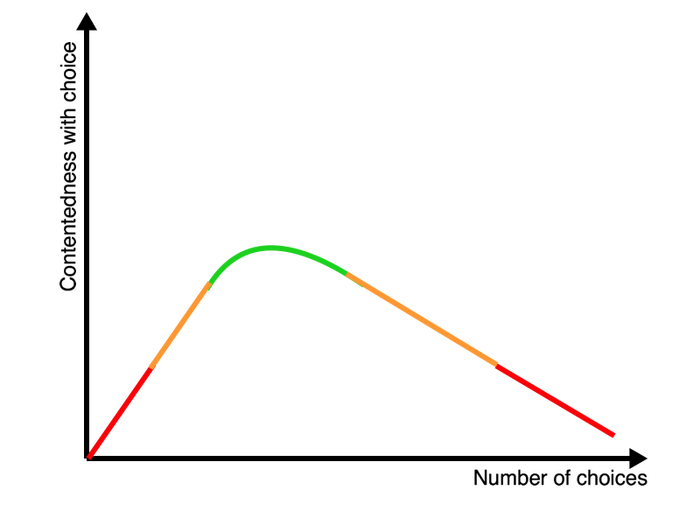

The abundance of learning opportunities and changing workplace dynamics can sometimes hinder rather than help. As the ‘paradox of choice’ goes, we are not always rational creatures that cleverly optimise our options: we are emotional too, and often an excess of opportunity can be overwhelming. It creates a sense that you could be doing anything, which creates a disabling fear of doing nothing.

To make matters worse, there is also a prevailing narrative that if we desire meaningful work we must discover it, not build it. We have a sense that our purpose can can only be found in our ‘nature’, if only we were able to pin that down.

The search for this ‘nature’ is echoed in the call-to-arms written in well-meaning online articles that everyone should “find their passion” or “ikigai”. We read interviews with people at the top of their field, rinsing and repeating the same old myth: that success can be accredited to something innate within them. We hear journalists proffering retrospective success narratives that these people were always “selling cakes outside their house” or “selling sweets in the playground” and it was that which made them a ‘natural entrepreneur’.

This emphasis on something being naturally within them, instead of built or practiced, drives many people to look inwards, shutting down even hobbies they’re curious in. They start to believe they’ll never be any good at them so it must not be worth their time.

So, what on earth are we meant to do?

What on earth can we do? When we are searching for fulfilment, time and flexibility all at the same time? When work titles don’t fit, and we’re on a hamster wheel of trying to find our life’s work?

Unsurprisingly, the most popular solution to this existential angst is to try to find another job.

In fact, in the U.K. last year 47% of people were actively seeking a new job, with 60% of Millennials open to moving roles. Whilst a job can fix some toxic factors affecting wellbeing — for example being underpaid or bullied — often seeking new work is not the solution. Deep down, people are frequently dreaming less of a new job but rather the permission to be who they are, and the promise to be appreciated for their own unique perspective on the world. They seek recognition for what professor of organisational psychology Daniel Cable calls their “authentic selves”.

Daniel Cable has suggested a different solution that helps people find their own purpose in their work: create your own title. Cable talks about the importance of this for keeping staff happy. He references the Make A Wishfoundation and shows how important it was for staff satisfaction for the staff to write their own job title. Employees called themselves ‘wish fairies’ and ‘bone hunters’ and it added a personalisation and levity to their day to day work. Other companies encourage the same in their slack profiles. The traditional functions of “Customer Service”, “CFO” or “Business Analyst” are swept away, to be replaced by the “Customer Hero”, “Money maestro”, ‘The Data Guy” and so forth.

This transformation isn’t just happening internally. We also see people take this on themselves on LinkedIn. People aren’t ‘Investors’ or ‘Marketing Managers’, they are ‘Mavericks’, ‘Gurus’, and ‘Chief Story Tellers’. Whilst this may help create some ownership over their day to day tasks, by reframing it in their own lenses, it creates little practical value in changing how they spend their days and evenings and what they’re able talk about on the weekend.

Instead of finding new work, or changing your title, I would suggest something else might be driving this workplace distress.

That’s it, really.

And the notion that you will find a solution to a motivational fatigue through a new job or a new title is wrong.

Work can be, and often is, meaningful and purposeful: when the mission you are working towards resonates, when the team gives you autonomy, and you feel a sense of progress and ownership over your work. However it can take time to find that, and these pillars are not always guaranteed.

If you are feeling exhausted, and like you could offer more to the world — instead of complaining or blaming your situation, you should try to prove it. The solution is to create your own environment. First by taking ownership in the workplace, and secondly, in your own time: start a side project.

Why Side Projects?

Playtime matters

Instead of seeing leisure time as time to only go to the pub or scroll Instagram, we should seek time to play, explore and to create: we need serious play. We should see ourselves as in control of everything, including our own careers. We should allow our side projects to service our daily work, and our work to help our side projects. It is less a work-life balance, but rather a life cultivated to include both work, play, and experimentation.

Jeff Bezos, who just happens to be the richest man on the planet, says something similar. In an interview with Mathias Döpfner the CEO of Axel Springer, he says “The reality is, if I am happy at home, I come into the office with tremendous energy. And if I am happy at work, I come home with tremendous energy. It actually is a circle; it’s not a balance.” Side projects allow us to lighten up, and get better at our work.

Side projects take the pressure off

Spending time on your own projects that you find important, puts less pressure on your job to fulfil everything you want from your lives. The 9–7 is no longer the main source of self esteem or identity, and you get empowerment and energy from your own self direction. In these projects you make your own decisions, you do your own learning, you are responsible for making them happen. You can experiment in a place where failure doesn’t matter — where you can practice the things you push to ‘one day’.

Side projects allow you to learn new skills

Whether you’ve ever wanted to learn calligraphy, or sell kombucha, practising on the side is a great way to learn new things. You can learn sales, basic P&L, product management, coding, painting — the list is endless. It’s an amazing way to learn new things without the self-doubt that might creep in in a commercial setting.

Side projects open up a world of great people

Do you know people who every time you speak with them, give you energy? The people who motivate you, who have an open mind, who build on your ideas? They may not be your best friends or your even good friends, but most people have a cluster in their network. These people are really important catalysts to get you through the hard work. When these people are brought together, through a shared energy to make things happen, magic happens.

The bottom line

The funny thing is this: by cultivating a different personal environment you actually end up pouring that confidence and autonomy right back into your day jobs — it’s full cycle.

By exploring what makes you feel awake, you give more to your current working situation. You wake up earlier, you go to bed earlier, you try new things, you’re happy to learn the more routine stuff at work as you see the value in it, you gain courage and you learn where your strengths lie.

The best irony is that by allowing ourselves to connect to the things that make us feel alive out of hours, we end up becoming better at our jobs anyway.