I first saw him close to 50 years ago on a stage in a high school production of James Agee’s A Death in the Family at St. Albans school in Washington. Tall, lanky and with shoulder length blonde hair, he played the doomed Jay Follett who dies in a car accident at the end of the first act. I fell in love with him, as we were all supposed to do, but it was the kind of longing, out-of-my-league desire that comes naturally to a 15-year-old National Cathedral School girl who thinks her thighs are too fat, her hair too wavy and her complexion too iffy to be considered girlfriend material.

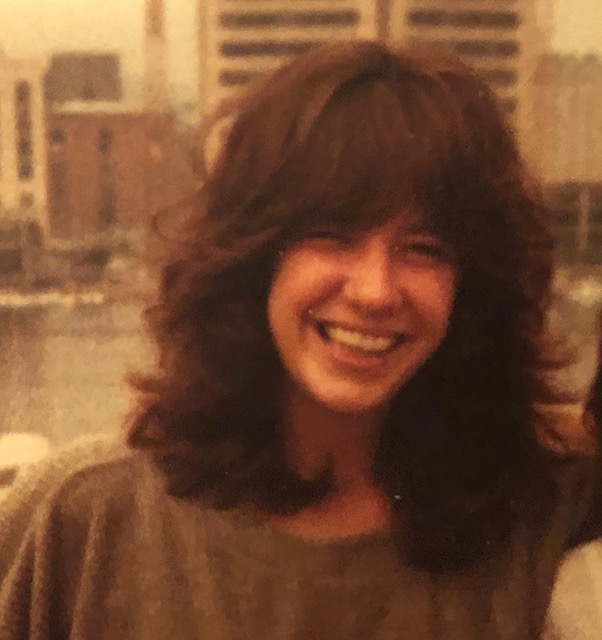

We didn’t speak until seven years later when I was living in an apartment in Georgetown and I ran into him at Booey Monger – the corner sandwich shop on Prospect Street. There he was, Jay Follett back to life behind the counter, gorgeous as ever with the nicest smile. I told him I knew him, but he didn’t know me. We fell into the kind of summer love that seems only could have happened in the late 1970’s – romantic and talky with minimal game. I was working at NBC News and got us tickets to a surprise Rolling Stones Some Girls concert at Warner Theater.

We stayed up until sunrise walking around our neighborhood while he told me story after story of growing up there – the son of a celebrated actress at Arena Theater and a father who died when he was just two. He showed me the alleys, playgrounds, abandoned buildings and mansions he had explored with wealthier kids whose parents were never home – adventures of privileged lost boys.

And then this idea of a boyfriend, this chimera of lyrical love, just up and left my life and moved to Europe. I didn’t see him for the next 40 years. And when I did occasionally think about him it was as if he was just part of that time, and it was perfectly preserved.

A few years later, I met and married a beautiful man – a network news correspondent who was the bravest, handsomest, smartest and most decent person I’ll ever know. We had three daughters and lived in pretty houses and had dogs and cats and dinner parties and trips and never-ending school events, bad teenage parties and finally, finally, graduations. When our oldest girl married, he walked her down the aisle at St. Alban’s church wearing the biggest smile in the world. And just as we were facing his retirement and an empty nest with mixed feelings (him glad, me not so sure) he got very sick and died very suddenly.

If an unexpected and heartbreaking death can be easy or poetic, we were blessed with one. While he was in the ICU, he developed something called La Belle Indifference– a hysteric psychological reaction to terrible circumstances. He was congenial, chatty and light-hearted, oblivious to the fact he’d lost his sight, the motion in half his body and could barely breathe. He spent the last night of his life looking at the door smiling at someone only he could see there.

Grief hit me with a swinging anvil of loss I could never have imagined. I remember struggling towards the phone the day after he died to call my friend Wendy also from high school who had lost her husband and his three young sons in a plane accident 10 years earlier to whisper if I’d survive this and she told me I would.

For the next three years I see-sawed between a stomach-churning anxiety about money and a deep excitement of a new life. I was a new 60-year-old self – single, strong and free, truly able to be and do anything I wanted. In-between there were dreams. The worse were at the beginning, I’d come downstairs to find him at his desk working and I’d tell him I’d had the worst dream that he’d died. And then I’d wake up.

Eventually the dreams stopped but I came to miss the pain of them as his absence became a dull, crushing, flat normal. That weight, along with a surety that he’d died on my watch. I had failed in the one job I’d signed up for at our wedding. He suffered and I didn’t stop it. We were still married; I was just the only one still hanging around.

I entered Widow World – where you bring your own cash to restaurants to pay the tip when other couples want to split the check, where you plan your Saturday night by Monday to get that out of the way, where the dishes stay where you leave them and television becomes your new very best friend. Where it’s just a matter of degree between luxuriating in white pajama crisp sheet tv remote bliss to waking up at 3:30 with a pervasive loneliness in that darkest hour.

I spent a lot of time with other new widows and one in particular said something that really got to me. “I have so many amazing friends who are women but sometimes I just get tired of them,” she said, “I miss men.” Now three years into widowhood I realized I did too. But I felt shy around them, exposed and toxic, like I’d been rejected from the garden. And the idea of dating, especially online, was nauseating. To try to please some stranger or hope he could like me when a perfect man already did, he just happened to be dead, was unthinkable.

But then I remembered what I liked about men. How they are bigger than me, how they smell, how they talk about things not feelings, the way they kind of miss the point sometimes (a lot), the antidote to women who try so hard to be thoughtful.

And then, like in the movies, my doorbell rang. I wasn’t home. But the young man I hadn’t seen or thought about for 40 years had heard about my husband’s passing and left a copy of his latest novel and a sympathy card at the front door. My adult daughters who were home for Christmas glared at him from the windows.

We had a few dinners – the old ease was there with an underlying tension of imagination. We smiled the whole time – the familiar tell of a first date. I learned he was married but living apart from his wife. I was married with my own separation thing going so it felt like an illicit but even playing field. The idea of exploration without mess, warmth without pain.

One night at La Piquette desire finally got the best of me. I told him I’d decided he was the person to bring intimacy back to my life. He walked me to my car, got in and asked if now was a good time. When we kissed, I was 22 all over again – a madeleine to youthful love.

He was staying with his now 100-year-old mother who didn’t miss a trick. I had my 27-year-old daughter and her fiancé living with me in my house. So, to continue with the teen theme of this story, we made out in the car.

I’m somebody who has never, ever been capable of keeping something important to myself but for the first time in my life I kept this secret. My children called me shady. I was awash in a physicality and yearning that made me feel like fainting.

Over the next few weeks, we talked about every single thing that had happened to us in the last 40 years. We explored our simultaneous childhoods and adolescence just a few miles apart in Washington. Without knowing it I was continually setting bars that he passed effortlessly. It turns out there was more than one man in the world who was kind, present, funny and very smart who liked me.

Van Morrison’s Crazy Love played on a loop in my car and I actually got fevers. If it’s possible to time travel then that’s exactly what was going on here. I was young and in love. Again.

The first night we spent together was the night Donald Trump was elected President. I came home in the pre-dawn hours to a houseful of stricken millennials and struggled to not smile ear to ear. I share this despite the category 5 mortification of my adult daughters who are also relentlessly teen-like in their gag reflex when it comes to their now 63-year-old mother and sex.

One day he and I were walking in the middle of O Street to find his car and I saw our reflection in a window and was surprised to see we looked cool. Me, a former minivan-driving mom-jeans-wearing parent peer facilitator senior citizen wearing jeans and boots and holding hands with a boyfriend. Good night.

Because here’s what I learned – late love is a combination of easy, gentle allowance with a reckless abandon unknown before. A more graceful intent. Sometimes it felt like we were exhausted life warriors at rest in each other’s arms. And because we were picking up where we last left off, there was an element of time travel as well – when I looked at him he was 24 years old to my 23. Old me is the old me again.

The lessons of my marriage and its end came back to me. Grief is love, albeit viewed through a blur of tears, and it continued to be there. But I woke again to what I knew to be true, that love brings love. What ended up saving me from literally wanting to just join my husband in his new place so we could stay together was not the dreamy notion but the feral power of love. The only way to make him being gone bearable was to keep what we had and make it part of who I was.

I have learned that love is transformative and essential – and simply requires an open, albeit broken heart. There is joy in this journey of grief. I’d dare to say it helped me fall in love all the more. The latest lyric in my head is Taj Mahal singing Giant Step, “It’s time you learned to live again and love at last.”

We’re still together and I continue to be grateful for this reappearance of the doomed young husband, this light and passion in my life. There’s a line towards the end of that play All the Way Home.

“How far we all come. How far we all come away from ourselves. So far, so much between, you can never go home again. You can go home, it’s good to go home, but you never really get all the way home again in your life.”

This is close enough for me.