My team and I struggled for a bit. We were looking for a word to capture, on our website the fifth and perhaps most important of our missions. A word that would presumably appeal to the so-called hardnosed, cold-eyed realists who run the world. And then in the midst of the struggle, I remembered that we shouldn’t have to adjust who we are, to fit those we want to change.

So I told them to leave it in. If a “human-centered economy” is what we wanted to encourage in the world, then a “human centered economy” was precisely what we were going to say.

Barely a week after, what turns up as the headline of the press release by Pope Francis to the denizens of global politics and economy at the World Economic Forum this year? “A human-centric economy is a moral imperative.”

Score one for warm and fuzzy.

I have spent the past few years of my life in these hallowed meetings, from the State Department to the World Bank, listening to the people who run the world speak about everything but the things that matter. I have contributed to those meetings, spoken at those gatherings, consulted for global blue chips and African governments, and advised foreign governments looking into Africa, and sorry, but I am not much impressed anymore.

It often seems like we speak about everything but what truly matters. Test question: what matters more? One more zero added to the value of Jeff Bezos’ stock, or one child saved from substance abuse in Malibu?

After my bout of what I call my ‘Big Bang Depression’ (which is how these things often happen isn’t it?) – four months of the first business crisis in my life, when I had to question who I was, what I was and, the gauziest of all questions, why we are here – I was forced to reassess my priorities.

To recall that time that I had a nervous breakdown and had to abandon leadership of our company and go off to the United Kingdom for a month less I lose my mind. Or the other time the doctor had done all the reasonable tests and, almost apologetically, asks if I would do a “HIV test” because he just didn’t know what else could be making me so sickly, and my insides so aged (Surprise, surprise: It turned out to be stress).

And when I had come out of this transformative experience, I had discovered that there was no other choice than to listen to the fundamental desire of the truest best self, signaled by the timeless self-discrepancy research of Columbia professor of management, Edward Tory Higgins from as far back as 1987.

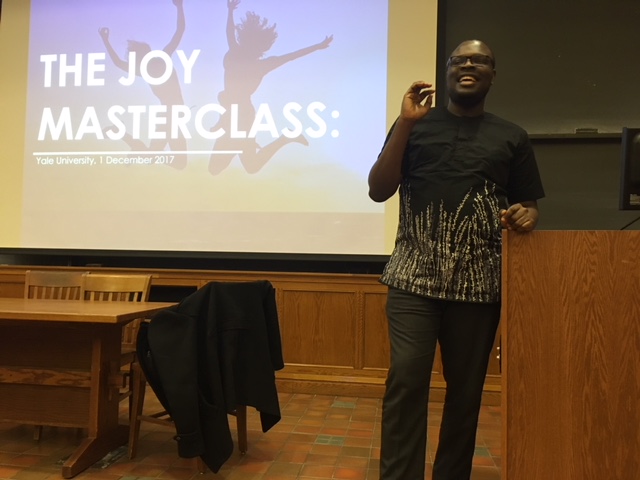

That journey led me to leave executive leadership of our media group, RED, with its wings spread across Sub-Saharan Africa, and start a new company called Joy, Inc., channeling a simple mission to create safe spaces of compassion, altruism and joy across Africa, transforming the culture through the media, and building a generation focused on the greatest happiness for the greatest many. Africa, because, if (in spite of its silent mental health crises) it can adopt and apply the findings from the massive research on flourishing and resilience, then it can leapfrog its considerable development challenges just as well as its leapfrogged over desktop, into mobile.

I have spent years helping build and lead social movements that have brought down presidents, changed governments and disrupted industries, and I have found out in those times the painful limitations of politics without meaning and economics without soul. To really deal with the decline of modern institutions and bring people’s sense of hope at par with the leaps in human progress over the past few centuries and decades, we need to, yes, heal our societies, marinate them in joy, and pay close attention to what the 70-year Harvard Grant Study tells us about “love” and “warm relationships” as the root of human aspiration, and fulfillment.

Of course, this will be as difficult as it is crucial.

In 2017, I spoke to an editor friend, for whom I had delivered several commissions previously, about the problem of African sit-tight dictators and how my story-pitch went deeper than just institutional decay and colonial displacement to the character of these players themselves. The fundamental lack of love and warmth that makes a person cling to power and domination, while millions suffer.

As a journalist and former editor steeped in a 17-year tradition of auto-cynicism myself, his answer didn’t surprise me: “It is difficult for me to take that argument seriously.”

It puts to mind the bemused tolerance that many writers often have when they refer to the 17th Dalai Lama, who has fought and withstood the most debilitating oppression known to man alongside his people, or Desmond Tutu who knows more about economic and political destruction than many people who sit at the United Nation’s General Assembly, as “pacifists”. We, after all, live in a world where a man is taken more seriously when he threatens nuclear warfare than when he asks for common-sense peace (Another test question: If these serious looking guys in suits really knew what they were doing, then why is the world in such a hoary mess?).

Well, they are going to have to deal with it moving forward. They might be able to ignore the tons of research across economics, sociology, psychology and management that make the definite case for what Jack Ma calls the “love quotient” or the stunning findings from Richard Thaler’s behavioural research, but it will be impossible in the future that is already here for them to ignore the army of determined, resolute minds, like mine, focused on tackling the world we have been given, and remake it into the whole, nourishing image that the growing, validated body of evidence is pointing us to – with increasing urgency.

It’s time to rethink the foundations of modern human society and our tired measurements for human success. This has always been urgent.