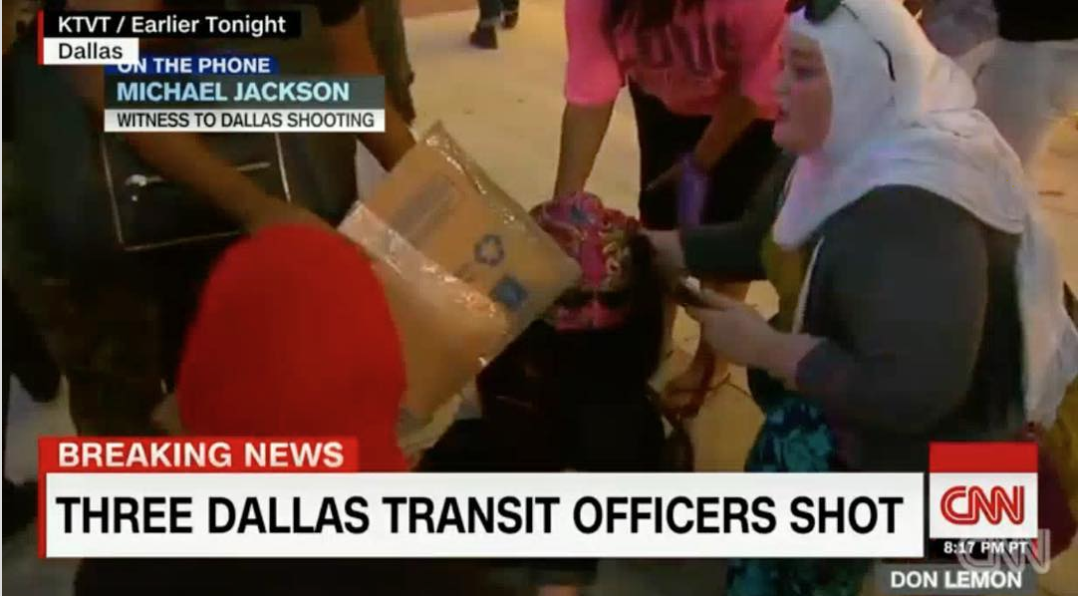

This month marks the fourth anniversary of the shooting at a Dallas Black Lives Matter Protest when five Dallas police officers were killed in retaliation during a protest against the killing of Alton Sterling, a Black man, in Baton Rouge. In that time, I don’t see significant positive change.

The list of black men, women, and children’s names who have been killed keeps getting longer. Eight minutes and forty-six seconds, police officers heard George Floyd calling out for his mother, air, and help while a police officer kneeled on his neck until he died. Eight shots from police officers cut down Breonna Taylor in her own home. Add to the list Elijah McClain, Ahmaud Arbery; we need to #SayTheirNames.

Each name comes with another protest: more names, more protests, but little change. Think of the fear and terror they went through in the last minutes and seconds of their lives. Most of us have never been in that position, so how can we empathize?

For me, the memories of protests following a murder are still vivid, and each news account of protests today makes me fearful and sends me back to that July day in 2016.

Four years ago, as the protest started, we listened to the speakers, raised our fists in the air, yelled in solidarity, and began walking. The sun was setting, and we marched towards the final location.

Sharp snapping sounds echoed off the buildings surrounding us. Sounds of shrieking started to ring along with the call of equality; violent hands pushed me backward, I was in the middle of a human stampede.

My brain caught up, realizing those are gunshots, those are screams, and people are running away while I am frozen. My friend Sahara grabs my arm, and I whip around.

Stumbling, confused, and trying to find her husband, she broke down. Eventually, we found him and hid inside the concrete walls of the John F. Kennedy memorial.

Inside we could still hear the echo of the gunshots. Youssef took charge of getting us out of downtown. As we escaped, police swarmed the area, guns drawn. A visceral fear raged through me. It is a sight I still can’t get out of my mind.

We had no idea at this point who was shooting at a protest about police brutality and the killing of black lives. Police who were moments earlier called out on their brutality of people of color, and now they came guns out and ready.

I thought, “I am about to die.” Our hands flew up, and we screamed.”‘ Don’t shoot!”

I felt resigned that I would die at the hands of a cop.

I’ve spent years cultivating empathy for others. Still, my mental exercises couldn’t even begin to put me within the same ballpark of the feeling I experienced that day for only a few short moments—people of color, specifically black people, experience this regularly and consistently.

The shooting that day changed me. And I can’t stand hearing another name of a life cut too short.

As a white American, my life is very privileged. I didn’t grow up with a silver spoon in my mouth, but I can live a ‘normal’ life. I can go hiking and camping alone wearing my hoodie and a baseball cap, and no one looks twice. If I stop to look at something for longer than a moment, I think nothing of it; my life isn’t in danger. If I linger too long, I don’t have a fear of being lynched.

Black people aren’t safe in their own homes; they can’t go running or hang out with friends. They can’t go bird-watching in a public park. The list of things black people can’t do safely keeps getting longer and longer.

Four years ago, we were marching for Black lives, and no good came from it.

Last month, last week, and yesterday we marched. Change needs to happen. No one should fear for their lives the moment they open their eyes.

It wasn’t until we were finally out of downtown sitting at a restaurant table that we learned what happened, how five Dallas Police Officers were slain, many more were shot. My sympathy will always go out to their co-workers, friends, and family for their loss of lives.

But often it is blue lives—the police– who are protected with automatic rifles, bias, and bulletproof vests; they can take their uniform off and live steeped in privilege if their skin color allows for it.

Four years have passed and we are no closer to justice and the fear is closer than ever.

Anniryn Armstrong is the Art Director and Administrator for Valley Ranch Islamic Center and a Public Voices Fellow with The OpEd Project. She created the Happy People Podcast, which talks to people about their passions, overcoming hardships, and finding common ground.