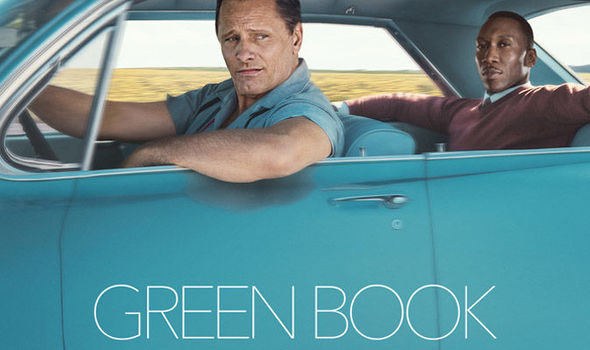

Amidst the racial tensions around us, I was struck anew after watching Green Book, a biopic about international African American concert pianist Dr. Don Shirley.

When I was in the sixth grade, I was labeled an “oreo.” Black on the outside but white at the center. I had never heard that before and I had never been put at odds with myself until that day.

I didn’t know that my demeanor at our diverse middle school could lead me to be perceived as anything other than a black kid. As I recall, the classmate hurled the comment my way because I jerked my head away after she tried to touch my hair. Silly, I know.

I recall that day vividly because it was the day I received an education on double consciousness which would later inform my perspective on the importance of code switching.

Double consciousness was coined by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1897 to describe an individual whose identity is divided into several facets.

“One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder,” Dubois wrote in the Atlantic Monthly article titled “Strivings of the Negro People.”

After watching the movie Green Book, I was empathetic of Shirley’s identity crisis as he developed a friendship with his tough-talking Italian-American chauffeur while traversing the Deep South on a piano concert tour in 1962.

I remembered the sixth grade and Dubois’ theory after Mahershala Ali, as Don Shirley, serves up the following line: “If I’m not black enough and I’m not white enough and I’m not man enough, then tell me Tony, what the hell am I?”

To be more formally-educated than people thought to be acceptable.

To possess less savoir-faire about African-American culture than was acceptable.

This was always a problem.

This was Shirley’s plight, too, and he caught it on all sides.

After studying psychology and music in the U.S. and Europe then garnering top achievements in his field, he began performing for audiences who wondered:

1) how he could be a doctor?

2) how he could be so virtuoso?

3) how he could have earned the support of two white musicians who comprised the Don Shirley Trio?

4) how he could speak so articulately?

5) how he could dress so well, walk with his head held high and think he could travel anywhere he chooses?

There was also a flip side, though.

After studying psychology and music in the U.S. and Europe then garnering top achievements in his field, he began performing for audiences who also wondered:

1) how come he didn’t play blues and jazz at local juke joints?

2) how didn’t he walk with a bop in his step?

3) how did he speak with such crisp articulation, forsaking typical Black vernacular?

4) how didn’t he wear Zoot suits?

5) how did he prefer lobster over fried chicken?

6) how was he unfamiliar with popular black musicians Aretha Franklin and Chuck Berry?

In the movie, it all came to a head when Shirley’s driver Tony insisted that he himself was even “blacker” than Shirley because he listens to Little Richard, enjoys Kentucky Fried Chicken and grew up in The Bronx, while Shirley has very little association with these rules for “black” living.

Enter double consciousness.

Mahershala Ali, as Don Shirley, spits back at him vehemently: “If I’m not black enough and I’m not white enough and I’m not man enough, then tell me Tony, what the hell am I?”

This becomes the quintessential question for those like Shirley and myself.

And now, enter code switching — the practice of shifting the languages you use or the way you express yourself in your conversations.

I had to learn that even though I didn’t prescribe to all overstated black American “rules” for living, it was okay to learn them for the purposes of freely navigating in and out of conversations and social settings.

Switch an “Aha…” for an “Ooooh girl, I feel you.”

Switch a Green Day reference for a Boyz 2 Men reference.

Switch a Friends reference for a Living Single reference.

All of this I had to learn and it began to serve me well.

In fact, by the end of the movie, Shirley also learned how well it could serve him.

He and Tony were dining at a juke joint and the bartender asked him to play a tune on the piano. While he’s used to playing on a Steinway for an audience of bow-tie, dinner jacket-donning high society folk, he chose to code-switch for his down-home Black southern audience, accompanying a blues band in boogie-woogie, syncopated rhythms that had both he and his Black audience sweating and grinning from ear to ear by the end of the set.

Lesson learned. As Black people, we are not a monolith.