Note: Be sure to read the definitions of the terms thinking and thought/ thoughting as well as concept and percept that appear at the end of this article.

Have you thought much about your thoughts? There is a difference between their content, like a difficult family problem, and the process of their appearance/ disappearance (bothering you all day long). Let’s take a moment to consider their processes and how you manage them.

Regardless of what they are about, all thoughts have distinct qualities, which include:

1. Duration (how long each thought lingers),

2. Frequency (the number that arise every minute),

3. Repetitiveness (the number of times the same one returns), and

4. Intensity (the degree to which they capture your attention).

In relation to the combination of these traits the term “thought energy” (TE) can be used. A higher TE involves long duration thoughts having high frequency, repetitiveness and intensity. A lower TE involves short duration thoughts having low frequency, repetitiveness and intensity.

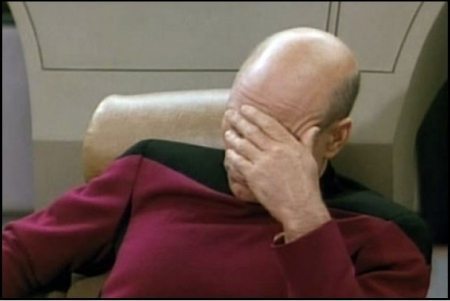

Do your own assessment. Got a lot going on up there? People pay therapists, travel, hike in nature, attend concerts, etc., just to clear their heads of thought. No one can play a sport, make their best decision, read, or concentrate on a card game with high TE. Often, that’s WHY people do these things—to get out of their heads (of too much TE). Some even resort to the thought-numbing effects of drugs and alcohol. Yet, thought can be so intrusive, chronic, intense and negative that people will risk their life to be rid of them. A clear-headed approach seems best for well-being and optimal decision-making. Agree?

An article in the journal Science entitled “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind,” by Killingsworth & Glibert (2010) offers some useful information. They used a smart phone app to get real-time reports about: 1. How often people’s minds wandered (when passively arising thought captured their attention), 2. What they wandered to, and 3. How those thoughts affected their happiness. Astonishingly, mind-wandering occurred at least 46% of the time. It also “…revealed that people were less happy when their mind’s were wandering….” Their research found that mind-wandering caused unhappy thoughts and was not the result of it.

Apart from mental clouding and unhappiness there are other downsides of a high TE. One is “preconception bias”—over-reliance on a too general opinion, like racial preference or optimism, before new facts are considered. It’s a death knell for any good, informed decision, like those for hiring a new person, lending or borrowing money, choosing a lover, or developing a new business proposition.

Attentive mindfulness clears the mind like a broom. Hitting a golf ball, reading, exercising, as well as many other activities all sweep the mind clear of thoughts. They do so because they require our attention. Attention sweeps thoughts away because they are incompatible with one another. To this point, Yogi Berra told the baseball coach who scolded him about swinging at bad pitches, said, “How can a guy hit and think at the same time?” My answers are: 1. You can’t, and 2. You shouldn’t. Our other information processing system does that kind of work. How do we do anything when thoughts are either gone or not used? We return control back over to our information processing system that uses percepts, not concepts. It’s really our main operating system but it’s hidden because we need concepts for thinking. Our other system relies on percepts for knowing.

Percepts are bits of information that comes to us through our senses that are in a more original form because they have not been changed into concepts (thought-words) and given “meaning”. Through this system we perceive danger, strength needed for braking a car, appreciate beauty, the truthfulness of a conversation with another, etc. It works continuously, efficiently and effortlessly without the use of any thought or thinking. Those who are consumed by a high TE may not believe even they use this system for the tasks above, but it’s true. To analyze conceptually, like “How much is 23 times 11?” thoughts and thinking must interrupt the workings of this system to come to that kind of answer.

Someone with established mindful attention, usually from the steadfast practice of mindfulness or meditation, lowers his or her TE score. The duration of each thought has shortened. None need to linger for more than a very brief moment. Even Einstein’s insight about relativity occurred in a flash of thought. The frequency of thoughts has decreased from lack of interest in the little of what repeated ones offer. Intensity, the most onerous of all thought qualities, also has weakened since the truth of their importance has become better understood by a more clarified mind.

Though it’s impossible to calculate, those well-practiced in mindful attention likely go for long periods without attending to or engaging any thoughts that passively arise. Yet, they can stop to think when that’s needed. Though the term “mental clarity” can be used to describe this mental state but it misses the quality of its depth and duration. The words “calm abiding” may be better, however. They may better convey the persistent attentiveness in combination with the mental clarity that comes from being undistracted by thought.

A good deal of valuable information is wasted when we use only one of our two information processing systems (either the conceptual or the perceptual). Directly accessed and untainted by the distortions caused by the alteration into concepts, the use of perceptual information has many benefits. For example, it cannot not suffer from preconception bias, like genderism. Gender is a concept and no concept is involved in this process. To the clarified mind, the processing of perceptual information offers insights, those unbidden but complete solutions that occur (e.g., that a animal-themed crossword puzzle clue “Bear” is actually not about the noun but about the verb). Every decision gets evaluated, as it should, only by the relevant information.

Before Seymour Epstein described this system in the 1970’s, which he called he “experiential,” not the “perceptual” information processing system as I do, it was unknown to academic circles. However, the meditation communities appear to have appreciated it for centuries. It became critical for resolving findings from behavioral economics research that were consistent but incomprehensible. Because of its importance for understanding how and why people make decisions about worth, understanding the powerfulness of this system helped Daniel Kahneman win the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics. Search for and look through the behavioral economics research articles published over the past 20 years. See for yourself. The work is fascinating.

It’s important to understand that everyone, including yourself, uses perceptual information to make sound decisions. Further, no one becomes stupid because thought has dropped away and mental clarity has returned. Perhaps this will encourage some of you to lower your thought energy through the practice of some sort of mindful attention. No harm will come and you won’t lose IQ points. Mental clarity, well-being and peace of mind await.

Terms:

1. As used in this article, the terms thinking and thought/ thoughting have different definitions. An active, intentional use of thoughts (concepts) within a rules-based system, like those using logic or time, constitutes thinking. Synthesis of information, arithmetic/ mathematics and planning, like for trips and buildings, all use thinking. Thought/ thoughting is the passive, non-volitional occurrence of the mental appearance of concepts. Daydreaming, insights, thought streams, and ruminations are all examples of thought/ thoughting.

2. Concepts are abstract or generic ideas generalized from specific instances. Words are all concepts, including those of “person,” “cup,” “finances,” and “law.” They only describe objects down to the level of a category. They do not and cannot identify anything unique or specific. On the other hand, percepts are the information we receive from our senses that characterize particular instances. As opposed to the concept “car,” which describes a class of objects, the percept of a specific car includes all of its the shapes, colors, sounds, smells, etc. You know when something is a percept when you cannot express it verbally. Though some incorrectly assume otherwise, colors, smells, and tastes are all percepts (often called sense-perceptions). They can be transformed into concepts, like red, for example. But, to people who could never see, specific instances of red, the redness of red, cannot be described. Percepts are non-conceptual and so cannot be expressed by words. They are literally indescribable.