Imagine the first taste of solid food you ever ate in your whole life. Your dopamine surged and it created the feeling of “Wow! Get me more of this” Let’s zoom in on that moment because it helps us understand the dopamine urge for more.

Here is a video of a baby having her first bite of food ever.

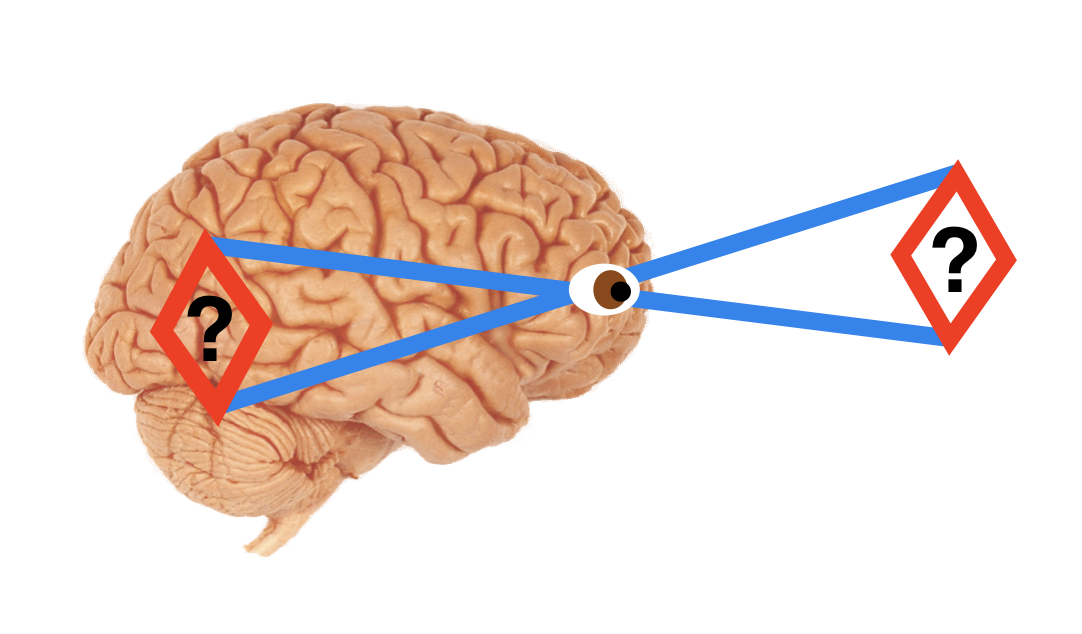

It’s fun to watch because she literally bounces with joy. But even more fun is the moment before the joy, when she’s still trying to make sense of the input (from 7 seconds until 12 seconds.) She freezes and her eyes widen, as if to say: “What is this? It is more rewarding than anything I have ever experienced!!!” She’s ecstatic by 26 seconds– it takes that long for the dopamine to do its job for the first time. The second time, the dopamine pathways it there and it will be instant. And a few days later, it will be been-there/done that, so it will take something new to trigger her dopamine.

Of course she doesn’t think this consciously, so let’s zoom in even closer on the biology of reward.

We are all born with needs we cannot meet for ourselves. A newborn baby does not even know what milk is. But when you’re hungry, your blood sugar falls and that triggers cortisol, “the stress chemical.” Cortisol triggers crying, and that brings milk which relieves the hunger.

The good feeling of dopamine is released when a need is met, so milk triggers dopamine in a hungry baby. The baby doesn’t need to comprehend its needs because the taste of sugar and fat triggers our reward detectors. Thus, the baby feels good before the milk raises its blood sugar.

Our natural reward detector is quite interesting. Anything that relieves cortisol is a reward from your brain’s perspective. So if you are dying of thirst in the desert, water is a huge reward. If you see an oasis in the distance, you jump for joy and dopamine releases energy that helps you run toward it. But in your life today, unlimited running water does not make you happy. You have to actually meet a need or relieve a threat to stimulate dopamine.

But our brain defines needs in a quirky way, which is why we do quirky things to stimulate dopamine.

Neurons connect when dopamine flows, which wires you to turn it on faster when you see something that triggered it before. When a baby hears its mother’s footsteps, dopamine starts flowing. These dopamine pathways help you find an oasis the next time you’re lost in the desert, but they also help you call the pizza delivery guy when you’re in a bad mood. Our brain anticipates rewards where we have experienced them before because pathways build when dopamine flows.

When a reward is more than expected, dopamine surges. A baby’s first taste of solid food is more rewarding than expected because solid food has more nutrients than liquid. A big surge of dopamine builds a big neural pathway, which provides big motivation in the future. It’s useful to understand this from the perspective of our ancestors, who started foraging for food in childhood. A little monkey is never given solid food— it only has breast milk until it gets something itself. But every monkey figures it out without textbooks or curriculum development experts thanks to dopamine.

Imagine your ancestors’ joy when they trekked toward a fruit tree and found a whole grove of ripe fruit. Our brain is constantly predicting rewards in order to make good decisions about where to invest your limited energy. When you stumble on a reward that exceeds your prediction, that’s essential survival information. A surge of dopamine wires it in to help you find rewards in the future.

Your ancestors did not get the same dopamine surge each time they returned to the fabulous fruit grove, because now it was already expected. They were still glad to meet their needs, but their fruit needs were soon sated and they’d get more dopamine by finding protein. Thus, the quest for big rewards helped them survive.

Dopamine feels so good that you want to do things that trigger it

This leads to a conundrum in today’s world of abundance. Our dopamine circuits motivate us to expect rewards that we never seem to get. Yet we keep repeating the quest because the dopamine circuit is still there.

A simple example is a teenager who wins at gambling. The excess reward builds a pathway that expects to win at gambling, which is a flawed guide to long-term rewards.

All the behaviors that frustrate us flow from dopamine circuits built by past excess rewards. You can probably think of ten such behaviors in ten seconds, with many variations of over-eating, over-spending, over-stimulating, and over-analyzing. It’s easy to focus on the frustrating circuits of others, but it’s useful to get to know your own.

You can’t go to Paris for the first time every day. So if you expect life to bring you that first-time feeling every moment, you end up disappointed.

But you may expect it anyway. Maybe you think other people are enjoying a constant flow of joy and excitement. Maybe you think you’ll get it as soon as you reach one promised land or another. When you’re disappointed, you decide that something is wrong with the world, or with you.

The solution is to know how your brain works

Our brain evolved to promote survival, not to make you happy. Dopamine evolved to motivate foraging in the world before supermarkets and birth control. Survival required constant effort, and dopamine made it feel good. Our brain saves the good feeling for steps relevant to meeting survival needs.

Fortunately, there is a way to feel good with this brain we’ve inherited. Small drips of dopamine are released when you step closer to a reward. You can let small drips be your guide instead of questing for that hit-the-jackpot feeling. Knitting a sweater triggers small drips of dopamine with each step closer to a reward. Once you’re finished with the sweater, you get a bigger surge when you look at your accomplishment, but you don’t expect the surge without taking the steps. Fortunately, dopamine makes the steps feel good as long as you see your progress toward the goal.

In the long run, you get more dopamine from steady steps than from big surges. But big surges lure you unless you know how your brain works. Get more information on your mammal brain from the Inner Mammal Institute.