“… a lived experience.”

It was the 10th of August 2013, and after fifteen years of chronic addiction, I had lost everything: my job, my mind, and every important relationship in my life. I was out of options, out of luck, and my body was rapidly deteriorating.

I finally decided that I needed help, but the world had other ideas. With too many drugs in my body, I was too much of an insurance risk for detox. They told me to come back when everything except opiates had left my system. Fearful that I would change my mind, I decided to go cold turkey at home. The next four weeks were the most painful of my life, but the hardship was worth it. I managed to stay off everything except opiates, and I was finally allowed to go to detox. Now there was just the minor issue of a 15 year opiate withdrawal.

The farm

Like something out of an IRA film, I was picked up on the outskirts of Dublin (Ireland) and driven to an unknown location about 20 km away. As I sat in the front seat of a beat-up mini van, I reflected on my predicament. I was entering the unknown, in more ways than one, but my new journey was strangely exciting. Energized by the idea of freedom, I was ready for the fight.

The detox facility was a little farm in the countryside. The long tree-lined driveway led up to an old house which sat in the middle of eight acres of land; four football pitches to you and me. The perimeter was lined with huge blackberry bushes and there was tranquil little stream that cut across the far right corner. Under different circumstances, it might have been a nice little retreat, but there was something about the place, something haunting, that seemed to hang in the air.

I was introduced to seven other addicts on my arrival, and over the next few weeks, we’d cook, clean, talk, cry, and look after the farm together. We grew our own vegetables and went for walks around the grounds. There was also pigs, cats, donkeys and chickens on the farm. I loved being around the animals, and I grew particularly affectionate with the chickens. Give me a break, I was about to go through hell hah!

Special worms

Detox was a weaning process, so baseline anxiety aside, the early days weren’t too bad. After three weeks, I was down to a dribble of methadone, 10 ml to be precise. This was tiny compared to my usual 100 ml dose, but I felt OK. I was amazed, and became fully convinced that withdrawal had given me a pass; be damned with biology. “Special me” came to mind — it’s an addict thing. While some people think that they’re special, others feel lost and depressed, like sad little worms in a big bad world. Addicts are different however, we think we’re special little worms, and that was me in a nutshell. But I was wrong; I didn’t get a pass. A few days later ‘the sickness’ hit hard, and every bit of ‘specialness’ was kicked right out of me.

It is difficult to describe what opiate withdrawal feels like. It is often compared to flu, which is close, but with several key omissions. It is a roller coaster of emotions, feelings, and physical sensations, many of which have not been felt for a long time. My gums were throbbing, my feet were on fire, my insides were a mess, and I was terrified of the craziest things, even my wardrobe.

But the most intense physical symptom was the fever. The sharp shivering sensations cut to the center of my bones. I vividly remember one night as I lay on the bed, quivering for hours, as the loneliness of the early morning seemed to taunt me. I put on as many clothes as I could, including my jeans, my jacket, and a huge grey bathrobe. I got back under the covers, but it was no use, I was freezing, and soon realized that time would be my only salvation. As I lay there trembling, cold sweat streaming off my body, it finally dawned on me why the mattress smelled so vile. I wasn’t the first one sweating in that bed; I’ll let your imagination run wild with that.

Ripples from within

The physical symptoms were bad, but manageable in comparison to what came next. Combined with chronic insomnia, the biggest challenge was coping with the intense waves of anxiety. Amplified to levels I’d never experienced before, it felt like electricity rippling up and down my body, or insects crawling under my skin. I wanted to run, but there was nowhere to go. One night I thought about climbing out the window, but I was afraid of my bloody wardrobe, never mind the pitch black night of the countryside.

I was now in the depths of withdrawal, and couldn’t face my bedroom anymore. I hadn’t slept in days, and spent the next six nights sitting at the kitchen table; all the other rooms were locked. It was a small kitchen, about 12 x 20 feet, and although it was homely, it was stained, worn, and old. As I sat at the end of the table, I wanted to run away from myself, escape the relentless anxiety; I must have done 10,000 laps of that little kitchen, but I couldn’t outrun my demons.

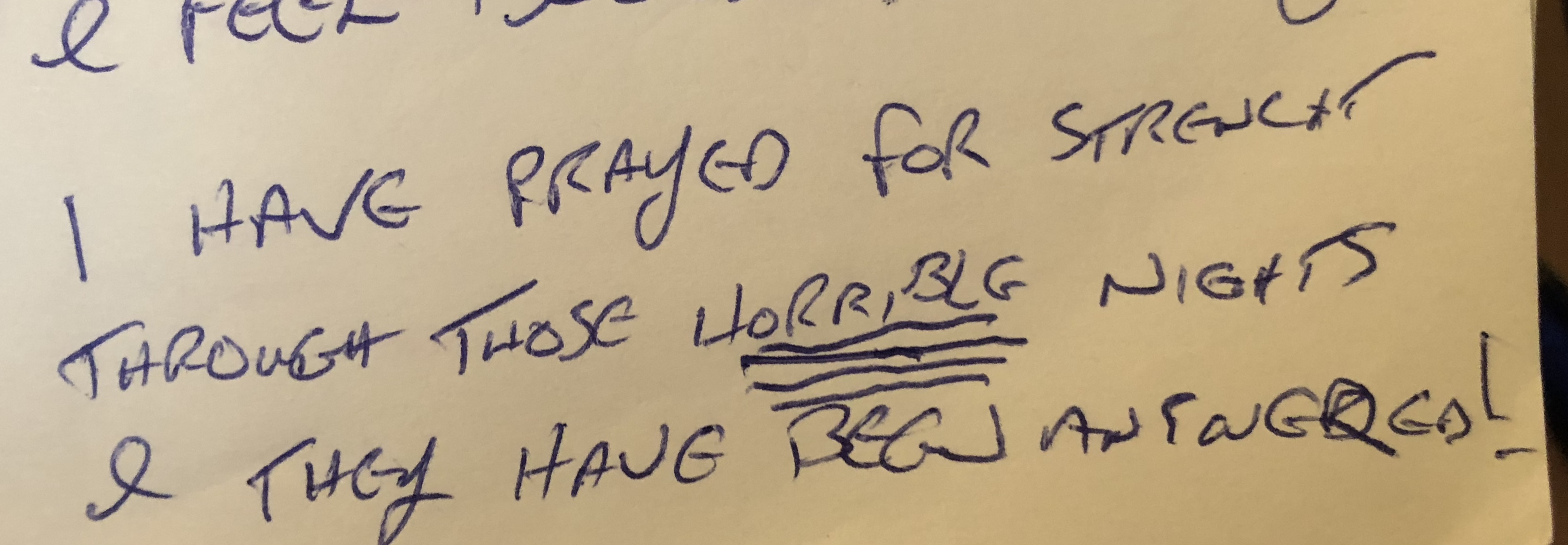

The nights stretched for miles, and I still remember the “Tick Tock” of the clock, chugging in slow motion. Again it seemed like time would be my only savior, but for the first time in my life, I was unsure if I would make it. I didn’t specifically think of suicide, but there was no end in sight, and I couldn’t see a way out. Now I knew why they locked the knives up at night. I’m not even mildly religious, but that’s when I decided to pray; it was all I had left. I had lost my grandma a few months previous, and we were very close. She was a devout catholic, so I just sat in the kitchen and asked her for strength. I’m still not religious, maybe I should be, because I firmly believe that my grandma got me through those nights. Below is a photo from the diary that I kept — the last word is “answered” — I must have still been shivering!

Take away message

After writing about my experiences before detox, which included ‘the most painful night of my life’, several people asked me what happened next. This article was my response, so I hadn’t specifically thought about a take away message.

On reflection however, the message here perfectly aligns with my mission in life: to show people that change is possible. It is exactly five years since I left detox, and in that time I’m proud of the changes I’ve made. I’ve rebuilt broken relationships, I’ve launched my own personal development business, I’m doing a PhD in Trinity College Dublin, and I’ve become a university lecturer teaching neuroscience, mindfulness, and addiction.

Using boldness as a core value, I’ve also reached out to highly successful individual’s in both Ireland and abroad. This has resulted in some fantastic opportunities, and I’ve made some unbelievable friends and connections along the way.

How did I make these changes?

I like to push boundaries, and that helps, but I made these changes through relentless consistency. I meditate every day. I read every day. I look after my physical and mental health every day. I neutralize negative influences from my life every day. I have identified my core values, and I act towards them every day. I don’t always do this perfectly, but I show up… EVERY SINGLE DAY.

“There is growth in suffering if you harness its power.”

You don’t have to take massive action, but you do need to be consistent. We are defined by what we repeatedly do, so just make a start, and your actions will breed more action. Before you know it, you’ll be making changes… EVERY SINGLE DAY.

Do You FEAR Change?

If not, check out the FREE program I developed to make extraordinary changes in my recovery from long-term heroin addiction.