When my second son was born, he didn’t open his eyes.

The nurse told us it was normal; some newborns take longer to part their eyelids. Through excited and exhausted anxiety, I believed her. But by the third day, we hadn’t looked into Jaxon’s distinct green eyes. We started making appointments with specialists.

Jax is now a creative, independent, and infinitely imaginative three-year-old. It turns out he was born without eyelid muscles and has a much narrower eye opening due to Blepharophimosis, Ptosis, Epicanthus Inversus Syndrome (BPES), a rare genetic mutation that affects one in 50,000 people.

With surgeries and other treatments, Jax sees just fine and can do everything any other kid can.

The worst side effect of his condition has nothing to do with his condition. Most people don’t notice or care about his difference. Too often, people stare. Others direct comments at him and call his amazingly designed eyes “weird.”

Given my profession studying leadership and organizational psychology, I scoured academic journals for anything that could help me be a better parent for Jaxon.

I found an answer in a children’s picture book.

As a family, we regularly read R.J. Palacio’s “We’re All Wonders,” a made-for-kids version of the 2012 novel “Wonder,” which chronicles a 10-year-old’s life with a craniofacial disorder.

In the children’s version, the fictional narrator “Auggie” Pullman shares his struggles with being left out and offers simple lessons on coping with feeling different. But on the last page, he has an important realization, saying, “I can’t change the way I look. But maybe people can change the way they see.”

After reading that line, I realized the worst side effect of Jaxon’s syndrome is 100 percent preventable.

You can change the way you see.

I’ve carried this lesson with me in my work developing leaders in communities and organizations. I find that most underdeveloped potential, behavioral concerns, and performance issues aren’t “people problems” but “seeing problems.”

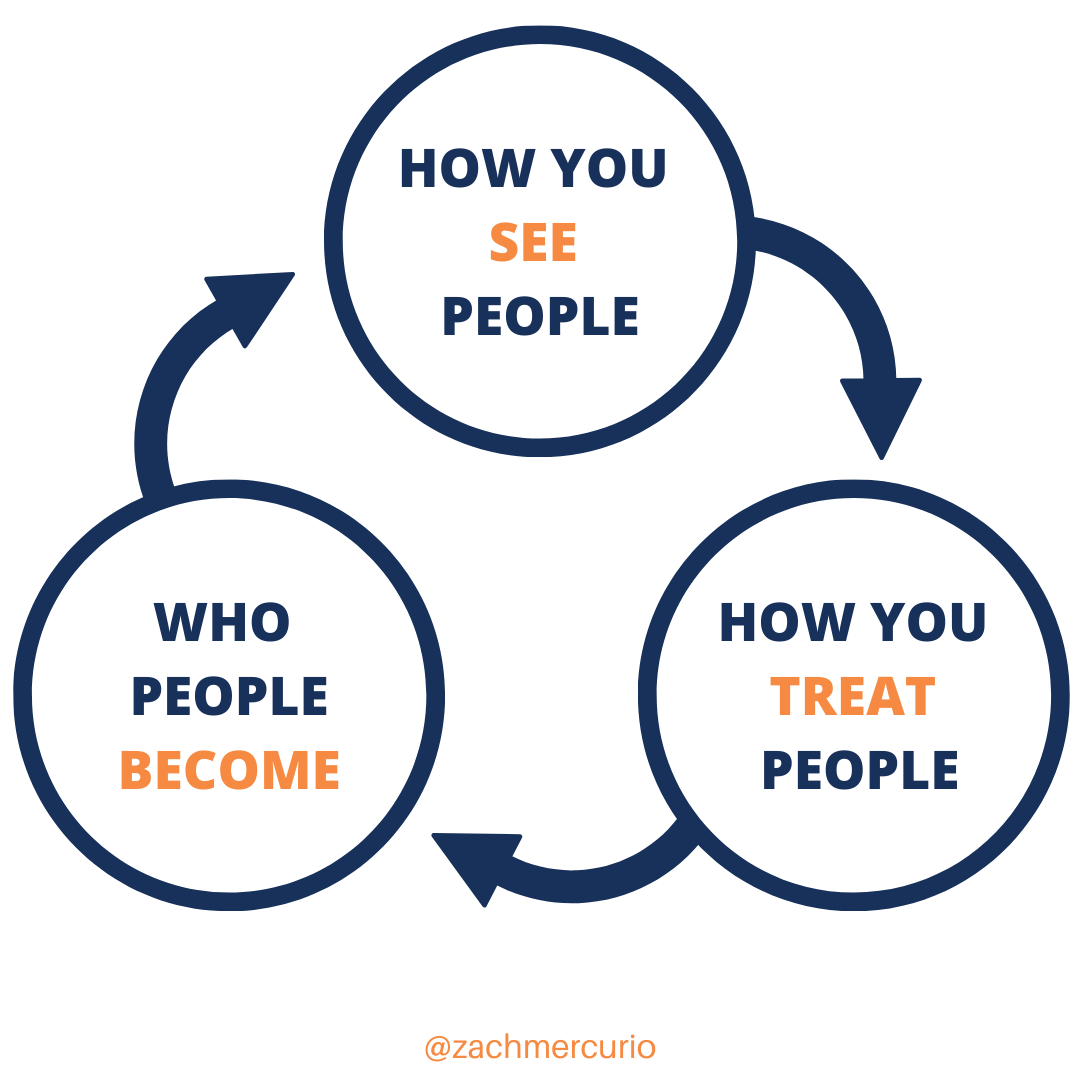

Writer, poet, and German statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote, “The way you see people is the way you treat them, and the way you treat them is what they become.”

If we want people to become better, we must learn to see people better.

The Seeing-Treating-Becoming Loop

I once worked with a high-performing new supervisor of a frontline manufacturing team. We started talking about difficulties he was facing, and he immediately shared, “Well, I have this one woman who always calls out ‘sick.’ She’s difficult and is just here to get a paycheck and leave.”

He saw her as “difficult and there for a paycheck.”

“Who do you want her to become?” I asked. He paused, then told me he noticed her potential and “just wanted her to feel proud of being here.”

“How do you treat her?” I inquired. He hesitated again, “Well, to be honest, I just try to avoid her and make sure she knows that her attendance issues could cost her the job.”

He was unintentionally treating her as he saw her: an issue to be dealt with.

I then asked, “What if you treated her like she had potential and you wanted her to feel proud of being here?”

If we see someone as “difficult,” we’ll treat them like an “issue.” If we treat them like an issue, they’ll think of themselves as a problem. Studies show that people with low self-worth exhibit increased stress, have difficulty in relationships, and frequently underperform in work and school.

The cycle continues.

How we see people is how we treat them. How we treat them is who they become.

Alternatively, if we see someone as “having potential,” we’ll treat that person as having possibilities. If we treat someone as having possibilities, we build self-worth. What do people with high self-worth do? Research finds they take more initiative, are more open to feedback, perform better, and are more resilient.

The critical idea that our perceptions of others influences how we treat them is well-studied.

In 1950, psychologist Harold H. Kelley published a landmark study on how our treatment of people is affected by how we perceive them. He had two groups of students read about a professor described as either “rather cold” or “very warm.” Then, the researchers had the professor teach a 20-minute discussion group with the students, behaving identically for each group.

The students who were told the instructor was “cold” were less likely to participate. They also rated the “warm professor” as much more humorous, friendly, popular, and better.

How we see others affects how we treat others.

So, how do we change how we “see” others and break the loop?

We must first become aware of how we see.

How We See Others

In psychology, the way we see others is called person perception.

Initially, we form perceptions of others by relying on physical and nonverbal cues. The limitation is that we tend to notice and remember negative signals while our brains scan our environment for threats.

In one study, Psychologist Tiffani Ito and colleagues analyzed participants’ brain activity while showing positive, negative, and neutral interpersonal cues. The brain activity was much more significant in response to negative cues. They concluded, “negative information weighs more heavily on the brain.”

Our brains also notice and emphasize characteristics, like clothes and facial features, that don’t fit a specific pattern. That’s why another child at Jaxon’s daycare kept calling him “the kid with the small eyes” instead of calling him “the kid with the normal-appearing nose, chin, ears, hair, etc.”

Second, our perceptions of behavior often result in labeling others by describing them in trait terms. There are over 18,000 trait terms in the English language. We describe others using words like “difficult,” “nice,” “creative,” “fun,” “quiet,” “low-performing,” or “high-performing.”

Studies show we make judgments about people by averaging traits based on our experiences with them. At first, that sounds fair.

The hidden problem is that we tend to average traits based on extremes and weigh experiences of a “negative” trait more significantly than a “positive” trait. We also favor certain traits, called “cardinal traits,” more heavily and tend to ignore moderatelypositive traits altogether.

Let’s return to the warm and cold example. Imagine you have two employees. A peer depicts Employee A to you as hard-working, on-time, warm, diligent, and practical. That same peer describes Employee B as hard-working, on-time, cold, diligent, and practical.

Researchers consistently find that the person described as “warm” would be perceived very positively, whereas the person described as “cold” would be perceived very negatively — based on one central trait.

Since we’re wired to point out and remember negative behaviors, we’re also more likely to ascribe negative traits to people. Further, the more recent an experience of negative behavior is, the more likely we are to label someone using negative terms.

For example, if “Joe” is late for two days in six months, but generally on time most days, your mind is wired to label Joe as a “late” or “irresponsible” person, despite all of Joe’s other positive attributes likely on display daily. And if Joe was late yesterday, you’re almost certain to view him negatively.

The cycle begins.

How to See Better

Fortunately, the simple awareness of how we see can shift our perceptions. From this new understanding, we can learn to see others better and interrupt some of the brain’s outdated routines.

In the process, we treat people better, and people become better, which is what leadership is all about.

Let’s try it. Take a moment to reflect on someone you might be perceiving negatively (this in itself is a revealing question!).

1. Ask: How do I see this person?

Write down two labels you’ve ascribed to them. Do you think they’re “awkward”? “Difficult?” “Challenging”? You can find labels any time you think or say, “This person is ___________.”

How did you form that perception? What information did you consider? What information might you have missed?

Now, list five positive traits about this person.

How does the way you see this person affect how you treat them? Do you treat them as if they’re defined by their positive traits or by their negative ones? How might your treatment be encouraging the behaviors you say you don’t want?

2. Ask: Who do I want this person to become?

Write down who you want this person to become.

Ask yourself: Am I treating them as what they’re not or as who they can be? What can I do differently to treat them as they can be?

3. Regularly reevaluate your perceptions.

Are you overweighing negative traits and under-weighing positive traits? Have you overemphasized a physical feature that doesn’t fit with your patterns of “normal”? Do you have recency bias, are you judging someone because of what they did this week?

To become a better leader, change the way you see.

And above all, before you make a negative judgment about anyone — an employee, a student, a passerby — remember this:

To someone, they are loved, and they are everything.

Jaxon thanks you.