When I meet with teenagers for the first time, one of my favorite questions to ask is which books they most enjoy. The majority have a similar response, along the lines of how they don’t really read “for pleasure” (although many do caveat this with the fact that they used to but no longer have the time- another troubling characteristic of the world in which our kids are being reared). Then, there is always a sample who boast of having social science-like books on their desk, a la Freakonomics or anything by Malcolm Gladwell, for example. Such books are great and can really resonate with people who love to read, because they are well-written and accessible, introducing complex ideas in layman terms. However, there is a fine line between a book written to simplify concepts, and books that are really research- and information- focused, that are absolutely not meant to be devoured by adolescents who have little-to-no exposure to high concepts of social science or academic research.

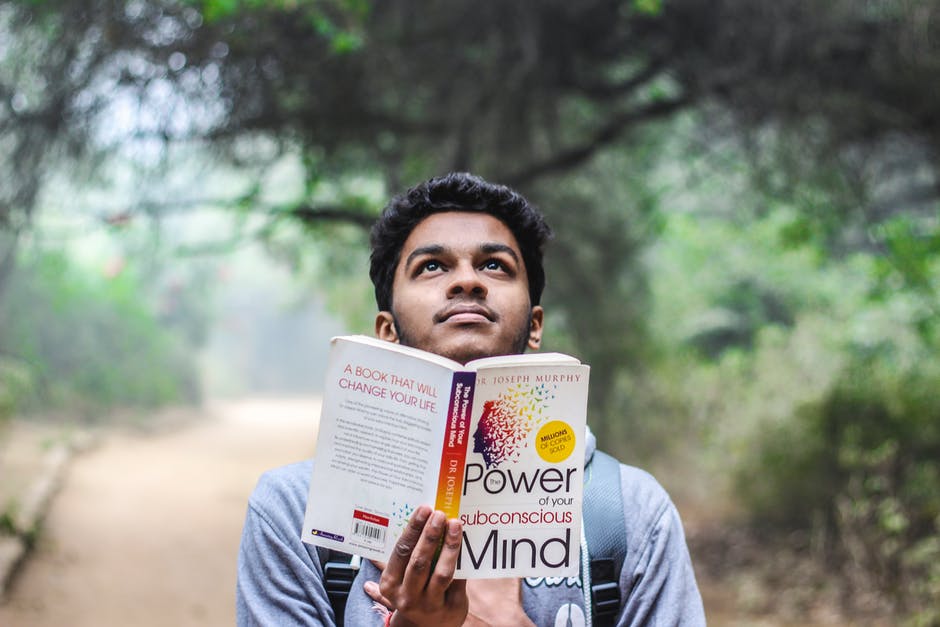

More so, there is a problem with offering a teen a Tony Robbins-style, 21st century self-help/business mogul/biography, a book filled with concepts that require introspection and perspective, particularly because adolescence is the time when teenagers are still developing these capacities.

We cannot ask a teenager to better himself, when he does not yet understand who he is. This would be like wanting to do home improvements even though you don’t yet own a home.

This brings me to a small point about reading, reading lists, and what is appropriate when it comes to our teenagers. “Best of”, “Worst of”, “Top 10”-style lists and those which utilize the same format are easy to write, easy to read, and usually difficult to argue because, at their core, they are opinion. That’s fine. What is misleading, though, is often the target of said lists, in particular those which tout the best books. I see these all too often. It’s the top books of the year, according to (insert: celebrity/mogul/politician/professor). The issue I have with such lists is a symptom of one of our larger cultural problems which is that while these lists are created by business and thought leaders, many parents read these articles for themselves but then assume that such books could turn their children into active and engaged readers, helping them “get ahead” of their peers who are stuck reading Twain, Heller, Fitzgerald, or Shelley, for example.

Yet, you know who I don’t want to give Harvard Business Review’s book recommendations to? Teenagers, that’s who. A list for “young leaders” does not mean ambitious teenagers! Without professional experience, these books have zero context.

The idea of professional preparation has flexed its muscles deep into the realm of everyday reading. Disregard the fact that instead of spending summers playing and reading literature, we send our teens to college programs that do nothing more than charge a bundle and keep parents feeling like they’re paying for progress.

It’s the hamster wheel playing out in real-life for teenagers.

I would argue that the student who does nothing organized all summer and is able to read 50 pages a day will end up a much more capable college student- and happier adult- than those who thrust themselves into every prep program and summer experience for which they can make space.

Granted, reading Tony Robbins is better than reading nothing at all. But are we really being thoughtful enough with our kids and encouraging a passion for reading? Here is a list of reading reminders for anyone who has- or interacts with- teenagers:

1) Book lists that include stories written by wall street executives, political heavyweights, and self-help gurus are not appropriate for teenagers. Period. The point is not to inculcate success stories but to encourage creativity, process, and greater ability to analyze and think about the human experience.

2) Creative literature such as novels, poetry, and plays, is everywhere. Go to your local library. Get recommendations from the librarian (librarians are AMAZING!) Encourage this.

3) Give them time on weekends to read. Read, yourself. Set aside specific family reading time.

4) Most kids will not like reading in high school because it’s required (and because they’re so busy). In the mind of a teenager- as well as many adults- something cannot be BOTH required and for fun. Understand this yet continue to encourage reading!

5) School-assigned reading can be stressful. Teachers are often looking for specific responses. Reinforce that when they have the chance to read for fun it is absolutely for their pleasure.

6) Start with short stories. Start with magazine articles. Start with documentary movies, even! Read- or watch- them together. Talk about them. Start slow.

7) If a high schooler is able to read just 10 pages per day, for pleasure, that’s nearly 50 more books (averaging 300 pages each) that they will finish outside of school reading, by the time they graduate. That’s WONDERFUL!

I don’t want this to be misconstrued as a bash on the book choices of people such as Buffet, Musk, or the Gates’. These individuals are not mentors for teenagers as much as they are for aspiring leaders and executives long removed from adolescence. I am willing to bet that when each was a teen, they took the time to read creative literature and use the lessons and metaphors to help drive them to be better, more humanistic, thoughtful, problem-solvers.