“If at any time during this training, my fellow instructors or I determine that we are not willing to follow you into combat, Gentlemen, you will not be here the next day. Am I clear?” he rumbled menacingly to the eight naval officers standing at attention.

“Hooyah, Instructor Rogers,” we stuttered loudly in reply, without much sincerity.

I felt like wetting my pants. I was scared shitless. I had been challenged before by men that wanted to see me fail. At the Naval Academy, I had led the class in demerits for screwing up in the many, and imaginative, ways I often found. Academy upperclassmen watched me and challenged me to fail. I had succeeded, despite their many and sinister efforts, and graduated, but there were many times in those four years that graduation was brought into serious question.

Now, this well-respected legend in the UDT/SEAL Teams was asking each of us to personally prove to him that we were capable of leading him into combat. We were all incredulous.

I knew how to shoot a rifle and a pistol; I learned how in the Boy Scouts. The two Army officers had yet to see combat, but they had trained with the best the Army had. This was a leap in logic that we could not easily grasp. Rogers had served, fought, and killed in the most demanding of combat situations—behind enemy lines in Vietnam. He had been tested, wounded, and found wanting for nothing. How could we prove our worth to a man like this? My own greatest achievement to date had been to avoid getting kicked out of college for misconduct.

“Dismissed, Gentlemen,” he stated with resolve. “Go join your class. They need you with them, and I expect you to lead from the front.”

There was a hopeful kindness in his voice, but most of us missed that.

We ran back in the dark early dawn and formed up with the class. For the instructors, PT had been a delightful start to a delightful day. For us it was a first taste of what was to come, and we all wondered where this day would lead us.

After the sixty minutes of exhausting stretches and calisthenics (and our introductory pep talk by Chief Rogers), the sun was beginning to peak over the horizon, and rays of cool sun shone onto the incoming surf crashing only a short distance away from the BUD/S area.

“Class 81, form up for the run,” came the next command, and we all rushed to form a four-column semblance of a formation, officers in front, that would depart quickly for destinations along the shore of the Pacific Ocean.

It was a wonderful day. The sun was shining, and the sand was soft, and I was not at sea on the grey monster made of World War II metal held together by rust and paint. I was only responsible for myself. There were more senior officers leading the class, and I felt invisible. This was a relief of significant proportions. To not have to deal with men sentenced to service in the Navy as opposed to jail was a vacation of sorts (military service was sometimes offered to young men by judges, as an alternative to incarceration).

Now I was standing with men of such high caliber that the recent past was just a distant blur. I reveled in the difference, and so did most of the others. We had found a place in the now-shrinking military where we could be proud of our mission and the men we worked with. The Underwater Demolition teams were jumping into the oceans to rescue astronauts and train sea lions to recover deep lost torpedoes. The Teams were still a secret organization—and rumors suggested they could eat John Wayne and his Green Berets for breakfast.

The run was over, and our daily PT was starting to make us increasingly fit and our muscles stronger and harder. It was time to make a run to the chow hall over one mile away, across the strand, at the Naval amphibious base. We ran in formation, with instructors calling cadence, to a well-earned and copious hot meal. The marines we passed paused to watch us. They had seen this passage of men in formation many times, and they knew our numbers would dwindle each week as training took its toll. There was a quiet pride among us, as none believed we would be the ones missing in future weeks.

The typical Navy-issue burgundy tray slid along the rails with an empty plate and plastic glass filled with iced soda. We were eyeing the food steaming in stainless trays ahead. We all needed to get as much as the plate could hold. Scrambled eggs in large mounds made way for a biscuit and sausage crumbled into white gravy, with the meat of the day piled alongside. Bacon (and necessary grease) with fried potatoes rounded out the plate. Grapefruit slices in sugar held space in a separate bowl. Toast with butter slid in next to all the rest with multiple strawberry jam individual serving containers. This would be our first trip through the line today. There would be one more for lunch. It probably tasted good, and I remember a feeling of great satisfaction when my stomach registered full, but quantity mattered, and a full stomach was the goal. Sometimes food choices were made based on caloric content, or solid versus liquid to ensure prompt passage, effective elimination, and subsequent tank refills. It became more and more important to learn what fuel worked best.

At 5 feet 8, I weighed a comfortable 155 pounds and had a touch of fat layered beneath my skin that I could pinch if I wanted. This fat would soon be replaced by an increasing muscle mass as it was burned for fuel. I felt fit, as I had been running and swimming and doing calisthenics every day. I was not fit enough.

In fact, fit was soon to be redefined in ways that would surprise us all—by repeated events consisting of prolonged pre-dawn physical training and long late-night ocean swims in colder-than-expected seawater, by obstacle courses, and by grueling long-distance runs. Most of us had played high school and college sports and had been coached by professionals who expected much of us, but nothing had prepared us for what was ahead. Today was a kind and gentle day comparatively. We all knew already that calories were essential to survival. Many would pack on muscle weight as training progressed. I would eventually weigh 175 pounds without a hint of fat to pinch.

We all noticed the changes. Run times targets decreased from early expectations of four miles in thirty-two minutes to the same distance in under thirty minutes, and the boots and sand were so much a part of the effort that we seldom had to think about it. Pull-ups and dips (a new exercise on parallel bars needed for the obstacle course) became enjoyable. Seaman Apprentice McNabb, our junior class member and a hardened farm boy, would show off at times by doing his pull-ups s l o w l y. That made them much harder, and impressed the instructors appropriately, since pull-ups were never actually fun.

It was still fun and exciting to earn a Navy paycheck, to workout daily, and try to earn a place alongside the men we had all seen on the walls of the building where we had reported for duty. I personally pictured myself in the ocean with a knife on my side, covered with grease for warmth like the World War II frogmen I had learned about. I had visions of leading men with amazing skills in combat. The Naval Academy had taught me of great battles and great men. I just wanted to be a part of recent history. Vietnam was over now, but it was still a very real part of the nation’s recent memories. Our instructors wore awards that most had only read about. It was humbling and a bit scary to think that we might be asked to work alongside such men.

Today it was all about preparation. Prepare for the next event. Take each day as a personal test of ability, stamina, and commitment. Most of us were excited with each new day, and we were in training with men equally driven to succeed. Thoughts of swimming, diving, parachuting, blowing up obstacles underwater, patrolling through enemy-infested jungles holding advanced weapons, and proving that we could be a part of this fraternity of warriors were things we all thought about but were not confident enough to express out loud.

Now was a time of testing. Now was a time to prove we belonged, one day at a time.

We moved as a class for the short run to the now-familiar obstacle course. The obstacle course was a test of strength and agility. It was timed, and failure to meet the fifteen-minute minimum time was common, but still unacceptable. We would all beat the required time eventually, and it would become an event to master and brag about—but now it was a small horror. Set entirely in soft sand, there were monkey bars to hand walk across, parallel bars to wobble or hop along with straight arms supporting the body, balance beams to run across, rope walls to scramble up, walls to climb that tilted towards you, three-story towers that were far enough apart that you had to jump up to grab each level, twenty-foot-high ladders that led to long ropes to slide down, and barbed wire to crawl under. It took twenty or more minutes to make it through the entire course in the beginning, but that would soon be a failing time. Technique and strength would develop together, or failure would follow.

But this morning’s obstacle course was going to be quite different for all. Petty Officer First Class Mike Thornton was reporting for training as our instructor. Everyone knew he was coming. ENS Muggs remembered having seen him in the hallway when he had reported in, and we all had heard the slightly unbelievable story of how he had saved his officer and squad on a mission deep behind enemy lines in Vietnam. That officer was severely wounded but made it back alive due to Mike’s extraordinary bravery, leadership, and superhuman willpower. What made it historically extraordinary was that the officer he saved had already earned the Medal of Honor for a previous mission.

He was intimidating to look at. He was also burdened for life with being known everywhere he went because of the Medal of Honor on his dress uniform.

Instructor Thornton was a large man with a serious face. He had thick, dark hair and muscles on top of his muscles. He had carried the burdensome M60 machine gun in Vietnam like it were a toy. He was unnerving, to say the least.

I would be introduced to Mike up close and personal very soon.

The obstacle course was becoming fun now. We were getting better at the techniques needed to pull, slide, crawl, and jump over and under the various challenges in the soft sand. Petty Officer Frank Winget, having joined us from a previous class, held the O-course record, and helped us all with technique.

I was happily in the middle of the crowd and was happy with my time, as I stood with the finishers covered with sweat and sand. So, I began to tuck my T-shirt into my pants, brush off the sand, and prepare for the coming three-mile run around the amphibious base.

Unfortunately for me, Instructor Joe Tyvdik, (pronounced Twi’-dik), a lean, strong, willow of a man, was watching over us all. He caught a flash of navy blue between the buttons of my BDU uniform pants and realized that I had very likely chosen to violate the rule to not wear underwear during training. This rule made sense to avoid the inevitable chaffing and possible infections that came from clothing and sand mixing in the groin area.

I knew the rule, and I understood the reasoning behind it, but we were going on a long run after the O-course, and I felt better running with some support, so I made a personal decision that I was sure no one cared about except me.

Oops.

“ENS Adams,” he crooned with an evil smile, as he sauntered dangerously towards me.

What have we here?” he continued as he reached for my groin area to display the blue and gold Naval Academy issue, Speedo bathing suit I was hiding under my uniform.

My mind was racing. I was a master of excuses. I could invent reasons for anything out of thin air with no notice. But as he reached for my groin, and I anticipated the possible trouble I was in, my mind froze. Nothing came to me. I needed to divert attention away from me.

So, I brushed Instructor Tyvdik’s hand away and playfully stated in mock horror, “Instructor Tyvdik, get your hand away from there. What are you, some kind of a faggot?”

I took this chance in a moment of panic. It was the best I could come up with at the time. It was a serious gamble made worse by being unaware of my surroundings at the time. I was smiling in desperation that the timing and humor was right and was rewarded with a surprised smile as he stepped back. It looked like I might just get away with it.

Only a few feet away, however, was another instructor, unaware of the flash of blue in my pants or why we were having this animated discussion, and he had heard my comment.

This was occurring as Instructor Mike Thornton trotted out toward the O-course for his first event as our newest instructor. Seeing a significant opportunity for entertainment and pain, the other instructor waited until Mike grew close. and then screeched for all to hear.

“Mike, that damn officer just called Instructor Tyvdik a faggot!”

We all froze. A dark cloud came over Mike’s face, while he slowed to a trot and pulled up right in front of me. I was petrified. This was not going anywhere near where I had hoped. Situational awareness had failed me.

He glanced at my name tag and gold collar bars of an ensign and screamed, “Drop for twenty, you filthy maggot!”

As I fell to leaning rest, he fell with me, and crammed his nose against my forehead as we moved together up and down in quick push-ups.

“Do you want to call me a faggot, Mr. Adams?” he screamed, as we pushed up and down, fused together at my forehead.

“If you even think about it, I will bite your head off, and shit in the hole.”

His spittle was spraying in my face, and I could feel the heat from his own red face. The other instructors and students were moving quietly and quickly out of range. I knew his threat was not physically possible, but damn

if I didn’t envision him doing just that.

“No, Instructor Thornton,” was all I could muster in return. The rest of the class was still coming in from the last barbed-wire-crawl obstacle on the O-course, and whispers were informing them of my predicament as they assembled to brush off and redo their uniforms.

“Get your ass up and get ready to run that O-course again, you filthy scumbucket. I want you to run that obstacle course again, right now. And I want you to run it backwards. Now go, and do not even consider not making a passing time.”

I took off immediately for the last barbed wire obstacle, as another classmate was coming through the correct way. I tried to think about how I was going to accomplish this task. I would have to climb up the 200-foot rope of the Slide-for-Life obstacle that we usually slid down, and I had never seen that done before. Other seemingly insurmountable problems lay ahead, but I was running on adrenalin, and was somewhat relieved to be on my own, away from a perceived certain death that had threatened me moments ago.

The class was formed up and ready to go when I crawled back to the original starting line, filthy and exhausted. Blood leaked down one elbow and dripped off my left hand from where the wooden edge of one obstacle had shaved off a chunk of skin. I was unaware.

“Mr. Adams, you are an officer, a leader. Get to the front of the formation and lead this run. Go!” he bellowed, as he pushed me forward, while I tried to catch my breath.

“Double-time march,” came the order, and the class leaped ahead on our planned three-mile run. The class had rested well while I had burned the oxygen from my muscles on the O-course. Now I was gasping to stay in front while my mind tried to assess the situation. It was grim.

After five minutes of running, we were entering the golf course area, and Thornton pulled me out of formation and ordered me to “hit the bay.” Glorietta Bay lined the edge of the golf course, and I sprinted towards the nearest wetness where I encountered cattails, and mud, and shallow water. I splashed into the wetness and rolled to get wet all over while the class trotted on. My boots filled with water.

“Catch up with your class Mr. Officer, you are supposed to be a leader,” shouted Mike as he propelled me towards the class. I sprinted with all I had and made it to the main group. If it were not for the power of adrenalin, I would not have made it. I slipped into the formation middle and asked those around me to hide me.

“Guys help me here. Hide me,” I panted as I wriggled into the middle.

“Oh, Lordy,” I heard whispered behind me.

They moved away. There was a hole in the middle of the formation with me in it. I was a dead man, and they all knew it. So much for teamwork today.

Five minutes further on, Mike had fallen back to harass some of the stragglers that were not keeping up, when he realized I was not back there. He saw a large puddle coming up on the dirt road ahead, came alongside the main group, and ordered us all to drop for push-ups in the muddy water.

“Mr. Adams are you in there?” he queried.

“Yes, Instructor,” I muttered from the middle of the now wet and muddy crowd, paused in leaning rest positions.

“I need you to head on back to the compound and save us all a lot of pain and suffering. Ring the bell now so we can get on with training. You sir are not going to make it. Today is your last day here. I promise you that, so take off now. Ring the fucking bell.”

I was stunned. “How did this happen? It was just a bathing suit worn to protect me.”

I looked up at this giant of a man, looked him dead in the eye, and whispered the words “No way.”

He read my lips and seemingly liked what I had mouthed at him.

“Get up you all and resume the run. Adams drop for twenty more,” he ordered, and I stayed in the mud pushing out twenty more as the class moved on, grateful to be rid of me. I finished and took off, as fast as my spent lungs could handle, towards the main group a hundred yards ahead. Some stragglers caught Mike’s eye and he took off after them. Again, I clawed my way into the main group of runners. I was on pure jet drive now and had no idea what to do, so I hung on.

The run ended back at the grinder, and only half the class was still in formation. The rest were spread out along the course being urged and threatened by the other instructors. We were ordered to stay in formation and march around the grinder as the rest of the class straggled in.

Instructor Thornton came in next and stationed himself at the chain link fence gate entrance watching the class come in. He was looking for me, sure that I must be huffing and puffing back in the rear. When the last few had come in, he looked around and asked another instructor where I was.

“He’s over there with the main group. He finished with the pack.”

“No fucking way!? Mr. Adams get over here and give me twenty push-ups again. Did you finish that run with the main group?”

“Yes, Instructor Thornton,” I panted as respectfully as I could.

“Well you just wasted your time and effort since this is the last day of training for you. Get your ass down to the ocean, get wet, and roll yourself in the sand until every nook and crack of your body is covered. You will look like a sugar cookie when you get back here. Go!”

Sugar cookie was the term used to describe a wet tadpole covered with sand. To achieve this uncomfortable state, a trainee had to get wet all over by leaping into the surf, run to the dry edge of the beach, remove helmet, and then roll over and sideways until the clothes, skin, hair, ears and eyes were coated in sand. Thus, resembling a human sugar cookie.

As I ran to the ocean, the rest of the class was ordered back to the barracks to change into dry clothing for the subsequent classroom event. When I got back, they were gone. I was wet and carefully covered with sand and held an extra handful to put on my head in case the helmet had rubbed some off. I already had sand in my mouth and ears in case he checked there. As I approached, I lifted my helmet and placed the sand under it. Sand was everywhere and falling from under my helmet.

“God damn it, Mr. Adams, did you just brush sand off your head?!” he shrilled, as if astonished. “I told you to have sand everywhere. Now go back and do it again correctly,” he ordered with emphasis.

He smiled professionally as I moved away stuttering my disbelief. He knew what I had done and why. He had done it himself when he was in training, but I was destined to fail today, if he had his way.

There was no response that would work in this situation, and I could not read his face, so I about-faced and headed back to the ocean. Sugar cookie he wanted, and sugar cookie he would get. The few minutes each way gave me pause to think of a way out of this situation. I had clearly crossed a line that I did not know was there, and now I was facing an angry nightmare wearing the Medal of Honor. I decided to go on. I could imagine no way out. I had no other choice. I believed it would end eventually, at least I hoped so.

Push-ups, sand dune climbs, flutter kicks, sprints to the ocean and back, threats, screams and anger, followed me for the next few hours. My arms were shaking, and my legs burned, and the ocean’s frostiness was feeling therapeutic when I was immersed in it time after time.

The class was obliquely aware that they had lost an officer as Thornton’s voice filtered into the class from behind the closed door. He had promised to run me out of training, and they were sitting as silent witnesses to this expected, inevitable event.

It was 1130 and the blood on my hand had long since dried. We had started the O-course at 0800, and I was in a leaning rest position, following a sprint along the tops of the undulating soft sand dunes, a dip in the ocean, and another roll in the sand. Instructor Thornton was once again entreating me to quit because what was going on was going to continue until I did so. I endured. It was the only hope I had. I spoke when spoken to and did the best I could to do as ordered.

I was in the leaning rest position again, back at the PT area. The water was pooling under me, and both my arms and legs were shaking with a mind of their own. I was looking straight down, and I was devoid of thought. I was in pure survival mode.

“OK mister, we are done here. Go join your class,” stated my tormentor firmly and officially, and he walked away.

I was left alone, confused, and exhausted as I watched my dedicated tormentor just walk away. My mind was processing what had just been said. I struggled up, looked around confused, spit grit out of my mouth. I stood up unsteadily and stumbled towards the nearby classroom filled with clean dry classmates. The teacher was at the board going over the lesson, and he paused when I opened the door and stumbled to an open desk.

ENS Muggs was sitting just behind me and was watching me carefully. Nothing was said. I was a dead man walking but returned from the grave. So, the instructor resumed his lesson, and I began to shake. Sand fluttered to the clean floor below me and my boots oozed seawater into puddles around me. I heard nothing, and I felt abused, confused, and angry. I had been thinking for the last few hours that my small crime did not justify this punishment. I knew that to some extent Instructor Thornton had to do what he was doing as both a new and famous instructor, and because he did not know me yet. Still I had been unable to think of a way to stop what was happening, except to endure. The longer it had gone on, the more unnecessary it had felt. I was confused. I had been harassed before at the Naval Academy by upperclassmen who stated they wanted me to leave, but there seemed more at stake now. To fail now, to not endure, would end everything before I had a chance to show what I could do.

My face turned red, and the shaking got worse as I contemplated the events of the past few hours. I felt like a piece of horse dung dropped onto a field of hot wet grass surrounding me. I did not know what to do now. What waited for me next?

“Excuse us please, Instructor?” asked ENS Muggs, a fellow Naval Academy graduate, as he stood up, gently grabbed my arm, and led me outside the room. This was an unusual move by a trainee, but the instructor saw that this was an unusual situation, so he nodded concurrence.

We moved together outside with my new protector supporting me physically. “Bob, you did it. You survived. Calm down and take a few deep breaths.”

We walked slowly back and forth on the sidewalk area, and I regained a measure of calm. Adrenalin was all I had been running on, and now it seemed like I had extraordinarily little left.

“That was uncalled for,” I muttered.

John agreed, but it was what it was. The purpose was not yet revealed. Eventually, after a few walks back and forth, as calm returned, and the reality of survival sunk in, I was escorted back to the class. I did not hear the instructor. I was lost in my musings. My biggest worry was that the test was not complete. What if I had made a fatal mistake? Could I go through all that again, and again?

The next morning at 0430, we again gathered on the grinder in our assigned positions for morning PT. I had just assumed my front row spot when I was summoned.

“ENS Adams, get your ass over here, and give me twenty-five,” growled Thornton.

Behind me PT began, and the whole class began their first set of jumping jack exercises. A few wondered if they would ever see me again. I began to think about yesterday.

As I finished the push-ups and held still in the leaning rest position, I looked up, in fear, for the next command.

Mike Thornton was seated on a platform over me, legs crossed, and watching carefully.

“So, Mr. Adams, do you remember yesterday when I told you I was going to run you out of training?”

“Yes, Instructor,” I replied as my mind tried to digest the horror of that statement. We had months and months of training ahead, and if I had to do yesterday again today, and every day, there was no chance I would survive.

“Well, I changed my mind. You did well yesterday. I am not going to run you out. As a matter of fact, I am going to make sure you graduate,” he stated calmly and with conviction.

I was speechless, and I felt the muscles in my back and legs relax. I almost wet myself.

“But let me be clear about one thing, if you screw up, you will answer to me, and the penalty will be severe. So, when you graduate, and you will graduate, there will be no question in your mind that you, sir, have been through training.”

Angels were singing above. The sun was peeking above the horizon just for me. A warm relief flooded over me.

“Hooyah, Instructor Thornton.” I replied and risked a small smile.

I think I saw him smile also when he turned away.

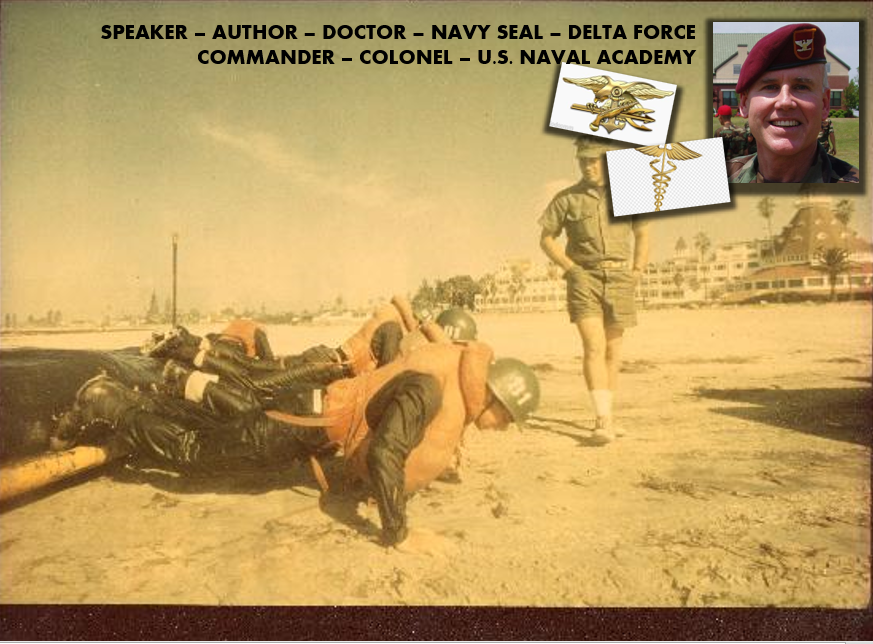

This is a chapter from my first book Six Days of Impossible Navy SEAL Hell Week – a Doctor Look Back.