By: Anna Rozwadowska, M.A. 2019; Habenom Gedey, BA, MD, MSc, PG-pain, CAPM, Dip.AM

The Technical Aspects

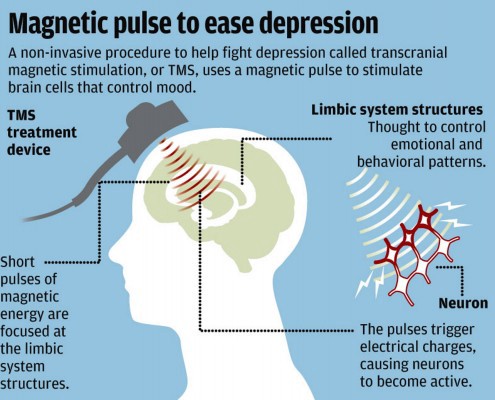

If you have not yet heard of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), in essence, it is a form of neuro-modulation; meaning that is works directly on the nervous system by stimulating certain regions of the brain, showing promise in the treatment of major depressive disorder, anxiety, as well as lesser known instances of conditions such as chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, PTSD, ADHD, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s and even helping in rehabilitation after stroke.

TMS is considered a non-invasive procedure (for example as compared to Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) ), where an individual receives multiple repeated stimulation in targeted regions of the brain (the prefrontal cortex) via a magnetic field generator coil that delivers pulses of electrical currents, in order to stimulate neurons (in depression) or inhibit neuron activity in people with anxiety disorders.

For the most part, TMS is still considered an adjunct therapy to medications and other treatments, however, it has been used and continues to be used as a form of single treatment for mood disorders, with increasing evidence of its efficacy as a standalone treatment.

What it Involves

In layman’s terms, one meets with a head psychiatrist or well-trained technician in TMS and fills out a questionnaire, while discussing the severity of their depressions or anxiety in order to map the motor threshold (MT) that is needed in the treatment protocol.

Then, one is placed in a recliner and a cloth cap is used to map out certain regions of the brain, where the targeted treatments will take place. The ‘motor threshold’ (MT) is determined, which is essentially the baseline electrical pulse generated for the individual. This will vary depending on severity of the mood disorder, medications, circumstances in life, and more. The baseline is typically around 50 %, but it is different for each person and the threshold may change throughout the course of treatment.

Typically, TMS requires a daily commitment of approximately 37 minutes each day, five days a week for 4–6 weeks to see the best results. Newer protocols with higher pulsation rates are now being offered, shortening the treatment time to 18–20 minutes. In the case of Patient X (real name has not been used) who received treatments at the NeuroMed Clinic in Edmonton, Alberta, she started to notice the effects around 3 weeks, but a great improvement in depression at around the 5-week mark.

While this may seem like a lengthy and expensive commitment, in a study conducted on the efficacy of TMS on adolescents by Croarkin et. al (2010) the authors claim that “one must also consider the real impact and suffering endured by adolescents with suboptimally treated depression. Current standard models of care for depression in this population include weekly visits to therapists, psychotherapy groups, and visits with physicians for medication management” (p.327).

Furthermore, the authors claim that “if these modalities result in suboptimal treatment, there is an increased risk of suicidality, psychiatric hospitalization, and further deterioration in developmental and biopsychosocial functioning” (p.327). Therefore, costs must be weighed with potential benefits and also, the problems associated with non-treatment.

Patient X has been using TMS on and off for over three years, noticing the difference when she was absent from treatment over months or when life circumstances changed, causing her anxiety and depression to flare up. Depending on the severity of the depression and anxiety, she would commit to 2–3 weeks of regular treatment, then go down to a maintenance dose of 1–2 times per week.

Unfortunately, TMS is uncovered by many insurance plans. This is in part because medications are considered to be the first line of treatment and that ECT is still used as a modality of treatment for anxiety and depression. However, even in Canada, momentum is growing as the technology becomes more widespread and there is increasing evidence that it works. Governments are starting to fund the treatments, though at a slow rate.

Background

TMS has been used widely in different parts of the world, as it was developed in the late 1950’s (though true application didn’t occur until the 1980’s) and used in countries such as Europe and the United States, but it has been gaining popularity as an alternative treatment or an addition to conventional treatments (e.g. medications) for depression, anxiety and more. Widespread acceptance of TMS in Canada is slow, though gaining momentum.

TMS was approved by Health Canada in 2005, but in the United States TMS is now covered by insurance policies in 41 of 50 states (Neuromed Clinic, Edmonton, Alberta).

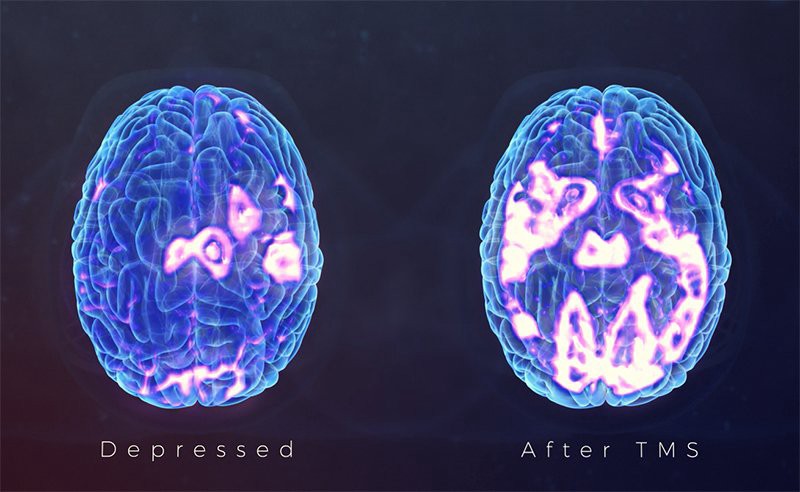

If you have ever heard of neuroplasticity, TMS generally falls into this category. It was once believed that the brain was static, where once injured or negatively affected it remained that way. However, now we know that the brain rewires itself daily, new synapses and connections die off and are built each day, making things such as recovery after a stroke and an improvement in symptoms of depression, anxiety and concurrent disorders possible.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, Neuroplasticity is “The ability of the brain to form and reorganize synaptic connections, especially in response to learning or experience or following injury.” The the proportion of grey matter can change, and synapses may strengthen or weaken over time.

One of the best source of learning about neuroplasticity is Dr. Normen Doidge’s “The Brain that Changes Itself.”

What this means is that there is hope for all of us.

The brain, no matter how traumatized or susceptible to anxiety, depression or even motor function problems, can change, and our realities can change as well.

TMS has been reported to have very few to no side effects, fostering brain change at the neurochemical level, just like medications do. The most common side effects reported from TMS are transient scalp pain and headaches. There have been little to no reports of TMS causing major problems such as seizures or memory loss, which is common with ECT.

The Evidence

According to the Neuromed Clinic in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, “To date over 100 peer reviewed publications investigating TMS in depression, including three multicentered randomised sham controlled trials, have been completed. The evidence is consistent regarding the effectiveness and safety of TMS in depression (Clinical TMS Consensus Review 2016).”

The Clinical TMS Consensus Review mentioned above was conducted by a team of experts on TMS in 2016, who reviewed over 100 peer-reviewed publications on TMS therapy in depression . They concluded that “ left prefrontal rTMS repeated daily for 4–6 weeks is an effective and safe treatment in adult patients with unipolar MDD that have failed one or more antidepressant trials.” MDD stands for Major Depressive Disorder.

Adult data support the use of TMS in depression as a safe, tolerable, and effective treatment1. One has to take into account the possibilities of adverse reactions when combined with medications or for multiple mood disorders, however, TMS seems to be well tolerated even for people on medications.

In two studies conducted by Quintana H. and Garvey MA., no adverse events were reported in 75 TMS studies including more than 2000 children. Though the use of TMS in children may raise ethical concerns, the studies show that the safety ratio is very high.

When I interviewed the head technician at the clinic where Patient X receives their TMS treatments, his approximation was that out of about 150 patients that he treated so far, about 40% showed complete remission of symptoms, 30% showed a reduction in symptoms while another 30% did not respond.

In a study conducted by Fregni et. al on the effects of TMS on chronic pain, evidence supports that “recent studies with non-invasive brain stimulation — eg, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) — using new parameters of stimulation have shown encouraging results.” It should be noted that further research and confirmatory studies are needed to demonstrate the true effectiveness of TMS on conditions such as chronic pain.

Last, in a study conducted by Dong-Hyun Nam et. al on 18 patients with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the study demonstrated that “3 weeks of low-frequency rTMS on the right prefrontal cortex was associated with a greater therapeutic effect than was the sham control treatment among patients with PTSD.”

Though this is by no means representative of the scope of research on the efficacy of TMS,

the above studies and increasing use of TMS demonstrate that TMS is emerging as a significant treatment in multiple and concurrent disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

References

1.) Croarkin, P. E., Wall, C. A., McClintock, S. M., Kozel, F. A., Husain, M. M., & Sampson, S. M. (2010). The Emerging Role for Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Optimizing the Treatment of Adolescent Depression. The Journal of ECT, 26(4), 323–329.

2. ) Dong-Hyun Nam, Chi-Un Pae & Jeong-Ho Chae. (2013). Low-frequency, Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the Treatment of Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: a Double-blind, Sham-controlled Study. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 2013;11(2):96–102

3.) Frengie F., Freedman. S., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). Recent advances in the treatment of chronic pain with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 188–91.

4.) Garvey MA. (2005). Transcranial magnetic stimulation studies in children. In: Hallet M, Chokroverty S, eds. Magnetic Stimulation in Clinical Neurophysiology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc; 2005:429Y433.

5.) Quintana H. (2005). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in persons younger than the age of 18. Journal of ECT. Vol. 21:88Y95.

6.) Neuromed Clinic in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Website: https://www.neuromedclinic.com/

7.) Tarique Perera, Mark S. George, Geoffrey Grammer, Philip G. Janicak, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Theodore S. Wirecki. (2016). The Clinical TMS Society Consensus Review and Treatment Recommendations for TMS Therapy for Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Stimulation, Volume 9, Issue 3, Pages 336–34