An Ancient Practice to Balance Modern Life.

It was a friend’s stroke that originally brought Dawn Sinton to a Yin Yoga class. Sinton (not her real name), who turned 80 this year, had tried Feldenkrais movement classes and gone to the gym her whole life, but had never tried yoga before. “The stroke had left my friend very off-balance,” Sinton recalls, “but she had been steadily improving. One day she said to me, ‘Dawn, you would really like this Yin Yoga class I’m taking.’ So I tried it: Now I think I go more than she does.”

For the first six months, Sinton found the classes very difficult. Working with Woodstock-based Yin instructor Will LeBlanc, Sinton began by focusing on special balancing postures. “I only see out of one eye,” she explains, “and over time that had affected my posture. When you’re blind in one eye it affects the muscles in your neck, it affects the muscles in your arms; your whole spine twists in a peculiar way that doesn’t help your balance.”

Even though it was difficult, Sinton found that she loved the practice. She was sleeping better than she had in years. (“If I wake up in the middle of the night, I do a series of forward folds: It’s better than a pill,” she explains.) During allergy season, Yin classes helped clear out her sinuses, reducing her need for antihistamines. In her daily movements she felt much more supple and found she was less accident-prone. Most important, Yin’s internal focus helped her to develop a “whole body consciousness” that began to permeate throughout her life. She felt tuned into her body’s needs in a way she hadn’t before. “It’s almost like a pendulum telling me what and what not to eat and when to eat. To get enough sleep. It acts as a monitor. When I don’t take care of my body, I feel it when I show up in yoga class.”

About a year ago, Sinton broke her kneecap. The adaptable nature of her Yin classes made it possible for her to continue practicing with just her upper body and uninjured leg. “I healed quite quickly,” Sinton explains. Recently, having her gall bladder removed waylaid her practice, but only for a month. “I was back at it,” she recalls, “as soon as the doctor would allow it.”

Yin for a Yang World

Yin Yoga is a slow, meditative practice that encourages students to shift their focus inward, not just toward their mental state, but to begin a specific inquiry into the body’s inner landscape. All poses are on the floor (no standing poses or headstands here) and most are held for a minimum of two minutes, and some for up to 20. Like other forms of yoga, Yin brings increased flexibility and decreased stress, contributing to a general state of wellbeing. “The health benefit I hear students describe most often is that they sleep better,” says LeBlanc.

The growing popularity of Yin Yoga is no surprise considering the “yang” nature of most people’s daily lives. (Since LeBlanc began teaching in 2003, he’s recorded a steady uptick in class attendance and interest, and has noticed “a very definite emerging of Yin back into the popular yoga consciousness.”) The sensory bombardment most people experience on a daily basis, coupled with the need in Western culture to look for logic and meaning in every situation, sets our minds into constant, often repetitive, chatter. The ubiquitous nature of electronics has only amplified and intensified our “monkey minds.” Yin Yoga provides the perfect antidote to this overstimulation rampant in modern life.

Originating in ancient India, a broad variety of yoga schools formed, principally with the intent of preparing practitioners to sit for meditation. “As yoga migrated to the West,” explains LeBlanc, “it was taught and then incorporated by teachers who standardized their own style of teaching.” What is now commonly thought of as yoga in modern practice is often one of the more yang or active-style yogas that have become popular in the West — Hatha, Vinyasa, or Ashtanga, to name a few. “However,” explains LeBlanc, “no one person came up with Yin Yoga.” It’s more of a blanket term describing a process of slowing down and sinking into one’s body. “This is originally what yoga was for,” he explains, “tuning into the wisdom of the body.”

However, Yin Yoga shouldn’t be mistaken for Restorative Yoga either. Restorative Yoga, which focuses on deep relaxation and healing, is often utilized to help students recover from injuries or excessive stress and relies heavily on props like straps and bolsters. It was exactly the search for a middle ground between active and restorative yoga traditions that brought teacher Bobbie Manchard to study Yin Yoga. A Manhattan-based yoga instructor, who often leads workshops helping other teachers incorporate Yin postures and philosophy into their classes, she wanted to find a space between the two extremes. “Life in the city is all about work, work, work and then flaking out in front of the TV,” she explains. Similarly, she found the yoga classes she led were either all yang-style striving or completely restive. “I felt there had to be a way to dial down, without just flaking out on a bolster.”

“I discovered Yin,” she adds, “and it was beautiful balance between the two.”

Freeing the Body from Within

On a physical level, the emphasis of Yin Yoga poses is not on stretching the muscles but on stressing the ligaments and opening the joints, pressing underneath the musculature of the body. It’s a subtle but very powerful change of focus. During practice, the muscles remain relatively inactive in order to focus on the myofascia, the body’s underlying system of connective tissue, just below and intertwined with the muscular system.

The myofascia, sometimes simply called the fascia, is a system of collagen, elastin, and reticular fibers holding the body together anatomically, connecting our various tissues to bone, joints, muscles, and internal organs, and holding our blood vessels and nerves in place, in a kind of mesh-like net. “Think of shrink wrapping,” explains LeBlanc. The fascia is not something we can necessarily feel directly, but as we naturally go about our daily lives executing repetitive movements — walking, sitting, driving, or even sleeping — the fascia tightens and holds the body in habitual patterns. When the body experiences the stress of even a minor injury, the fascia holds onto this stress as well. This fascial tightening can have a wide range of effects on our physical wellbeing, causing stiffness and pain in the joints and muscles, disturbing our sleep, and even affecting our mental and emotional health.

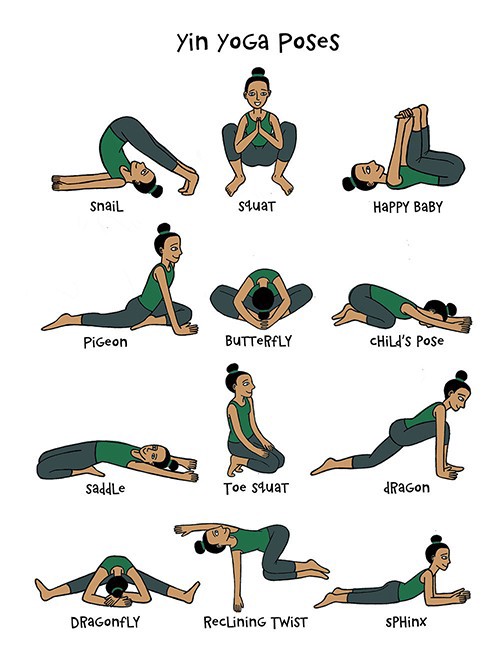

Classic Yin poses such as Dragon (a long, low lunge with the back knee on the floor) or Butterfly (a forward fold over legs held in a diamond shape with the soles of the feet together) gently release the fascia that’s holding our inner body in place. Yin Yoga can also be very effective at releasing pain in the joints and keeping them supple and healthy. Saddle pose (sitting on the knees and then gently reclining backwards) can help renew the synovial fluids that lubricate the knee joints, while Toe Squat (sitting on the knees with the toes pointing forward and then gently shifting the body’s weight backward) loosens and releases the joints and ligaments in the feet. (Note that Yin Yoga uses English names for the poses, rather than the Sanskrit monikers that many other forms prefer.)

“The trick of Yin Yoga practice is finding the right balance between effort and surrender,” explains Danika Hendrickson, who teaches Yin classes throughout the Hudson Valley. “For a Yin class to be effective, students have to find a way to let go of muscular effort and striving, and focus more on just being.” With regular practice, the body can let go of old physical habits that aren’t helping, and very often are harming, our health. Simply put, releasing the fascia literally frees the body from a microcellular level.

Revisiting Discomfort

This process of release has tremendous benefits for the sympathetic nervous system as well. The sympathetic nervous system, which controls our “fight or flight” response to stimuli, is given a third option through the practice of Yin. “There is a realm of spiritual detachment and disembodiment in yoga and other alternative practices,” explains LeBlanc. “Yin is the opposite of that.” Rather than having the goal of feeling “good” or detaching from pain, the focus of Yin, on both a physical and spiritual level, is to change our relationship with discomfort. (Detaching from pain, however, doesn’t mean ignoring it, which can lead to further injury on both a physical and psychological level.)

With Yin, “poses are an open framework that lead to a body-based meditation,” explains LeBlanc. True to the Yin philosophy underlying his practice, no two of LeBlanc’s classes are the same. Rather, LeBlanc uses his own personal daily Yin practice as a point of departure, then lets classes unfold naturally from that place. The class then evolves and adapts as he observes the attending students’ needs. Through this process, “the visceral experience of the body becomes the meditation”: Students have an opportunity to review their relationship with any discomfort and investigate what that discomfort is communicating, ultimately establishing a different relationship with both emotional and physical pain.

The general focus of Yin Yoga is to become more attuned to and observant of the body; this, of course, includes the mind. “Yin Yoga can be a natural gateway to meditative practice,” explains Manchard. “The yang styles of yoga can be very beneficial in stretching and releasing the muscles; however, a student’s mind might never stop racing and their nervous system isn’t always calmed.” In order to help her students fall below the mind’s constant chatter, Manchard begins each of her classes with a “sensory drop” exercise. Designed to help students get beyond their dominant senses of sight and sound, the exercise helps them attune to their physical bodies. The next step is a series of exercises focused on relaxing the mouth and jaw, which help to quiet some of student’s inner chatter. These beginning exercises open students to being more observant of their bodies. “Through observing the body, there are keys to unlocking the emotions the body is holding,” says Manchard. “Yang classes are led and a teacher is adding something. But Yin classes are more agenda-less; with Yin, something is being taken away.”

The largest benefit of Yin Yoga practice Manchard notices “is that students give themselves permission to go slowly, be quiet, and move away from stimulation.” Hendrickson goes a step further. “We are all so used to the constant pressure of having to make things happen,” she says. When we are able to tune into our own intricate inner landscape we discover that “the body has its own intelligence.” There is the realization that all our anatomical systems, from the nervous to the circulatory to the lungs and even the brain, proceed without our direct control. “The body is really taking care of itself.”

This, agrees LeBlanc, is the true lesson of Yin practice. “The body is our best teacher,” he explains. “Honor its wisdom.”

RESOURCES

Danika Henrickson will lead the Relax Into Being yoga workshop at Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, May 12–14. Eomega.org

Bobbie Marchand will lead a Yin Yoga Intensive Training at the Yoga House in Kingston, May 19–21. Theyogahouseny.com

Will LeBlanc teaches two-hour Yin Yoga classes at Euphoria Yoga in Woodstock on Monday, Tuesday, Saturday, and Sunday. Euphoriayoga.org

Originally published at medium.com