Dr. Judson Brewer is the Director of Research and Innovation at the Mindfulness Center and an associate professor in psychiatry at the School of Medicine at Brown University, as well as a research affiliate at MIT. He is a thought leader in the field of habit change, applying a mindfulness based approach to treating addictions. He is the author of “The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes To Smartphones To Love – Why We Get Hooked And How We Can Break Bad Habits.” (Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

What led you to focus your research at medical school on the neural mechanisms of mindfulness?

I started meditating on the first day of medical school. I had just broken up with my fiancé, my college sweetheart, and I started meditating to help me get through it. I had no intention of researching meditation. It was the mid 90s, almost a decade before the first research paper on meditation. I spent 10 years meditating without joining the two at all. Instead, I studied genetic mouse knockout models of stress and was looking at stress from a molecular biology point of view. I saw there was so much commonality between the way buddhists spoke and the way my patients with addictions were talking about their suffering. That led me to decide to switch my research career to studying the translational neuroscience and clinical effects of mindfulness. I was doing my residency at Yale and when I announced this move, people thought I was killing my career and started distancing themselves from me.

Why is it even important to investigate the science behind mindfulness? What does an understanding of science bring to the study of mindfulness?

As a scientist, I always want to know the mechanism that underlies something as by doing so I can hone in on the relevant pathway in the body and design treatments that are more effective for patients. For example, in our first study for mindfulness training for quitting smoking, we achieved 5 times the rates of smoking cessation as the gold standard in conventional medicine. I wanted to know why this was the case. We tested formal practices such as sitting meditation and loving kindness meditation and informal practices such as paying attention while you were smoking. Interestingly, it was the informal practices that led to the decoupling of craving from smoking. Once we ask the smokers to really pay attention to the act of smoking, they start to notice the burning feeling as they inhale, the terrible taste and unpleasant smoke. They began to see that it is really not that great. Simply paying attention to the experience of smoking was enough to decouple the link between craving and behaviour, breaking the habit loop.

How did you apply the results of this study to develop mindfulness based treatments for patients suffering from addictions?

Whenever I looked out the window of my office at the VA hospital, I would see my patients out in the parking lot with their cigarette in one hand and their phone in the other. Since habits are learnt in the context you form them in, I thought, would it be possible for me to bring my office to my patients whilst they are in the parking lot. That is when we started making some of the first evidence based training applications on smartphones to allow patients to unlearn their behaviours in the context they associate them in. We found that providing this scaffolding to help them break their addiction in the same context radically changed these habitual behaviours. It is because our memory is set up to learn with context. From a survival perspective, memory learns from context to allow us to remember where food is located and where the danger is.

A lot of people go to therapeutic communities or rehab to get rid of an addiction. And while they are in rehab, they often don’t get any cravings because the brain is smart enough to think ‘why should I bother craving when there are no drugs here’. For instance, a man was in a therapeutic community for a year and a half and on the same day he got out, on his train ride home, he called his dealer. The craving hit him so strongly and he had no idea what to do with it. So the only way to unlearn these ingrained habits is to unlearn them in the original context where the addiction was formed.

Your research found that experienced meditators show reduced activity in the default mode network. What is this region of the brain responsible for and why is it reduced in those who have a regular meditation practice?

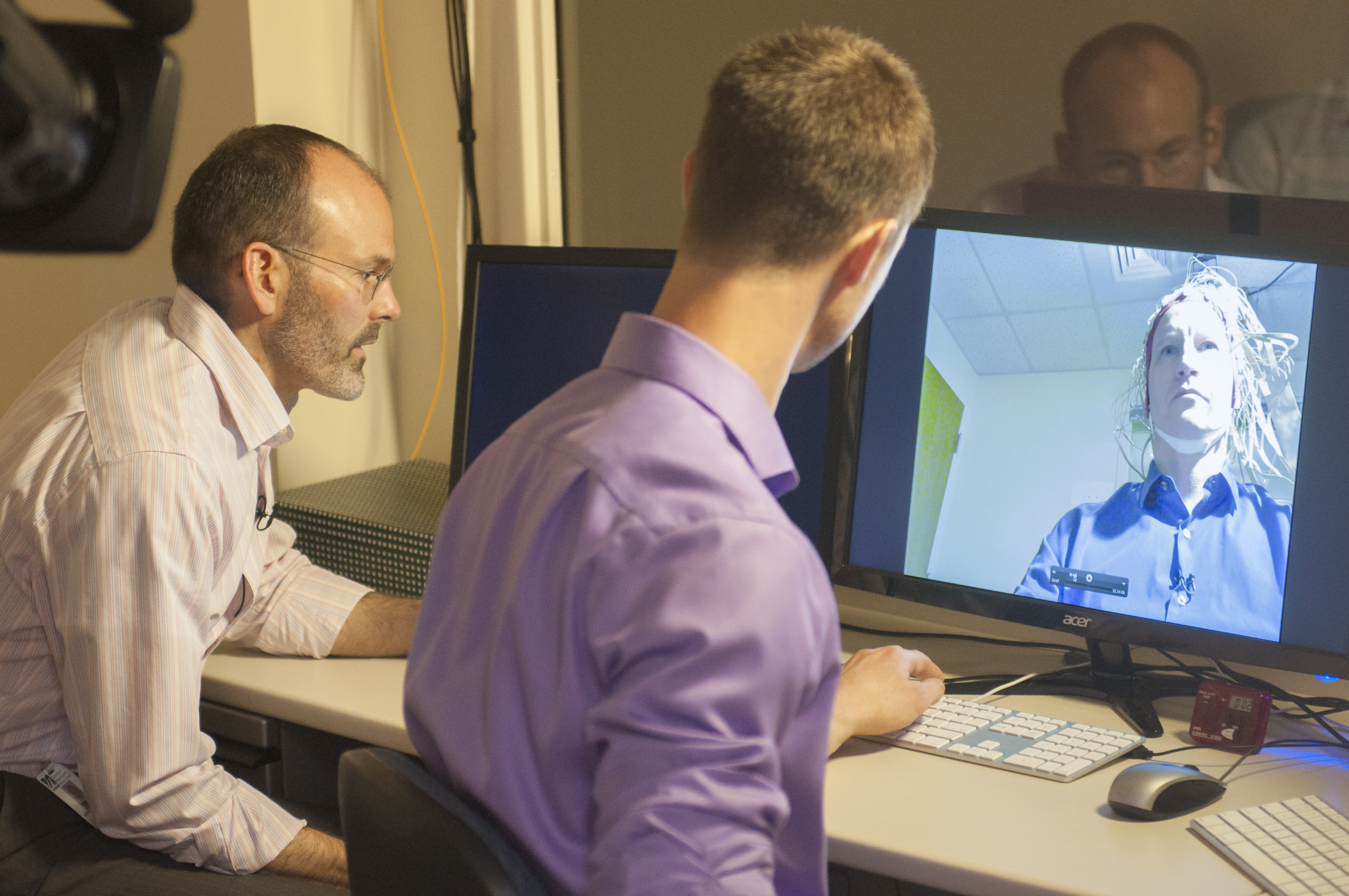

The default mode network (DMN) is activated when we get caught up in cravings and rumination. That feeling of being ‘caught up’ is something we can actually measure neurally. We carried out an EEG (electroencephalogram – a test to record electrical activity in the brain) and found that when they think of something that stresses them, their DMN fires up, and when they meditate, the firing stops. Experientially, we all know what it feels like to get caught up – it’s this closed, contracting feeling you get when you’re anxious or worried about something uncertain in the future, as we all are right now. The DMN is involved in this self-referential processing. It’s essentially a marker of the self. We found that one part of the DMN, the posterior cingulate cortex, seems to be a marker of the experimental sense of self. Mindfulness helps us stop taking things personally and let go. When this happens, that contracting, closed up feeling moves into an expanded quality. We found that meditators show decreased activity in the DMN and this correlates to an expanded sense of being. That expansion happens when we let go and mindfulness directly helps us do that.

Your results are groundbreaking. You have shown that mindfulness based therapy has higher results than the traditional gold standard in treating addiction. Why are we not seeing widespread adoption of mindfulness therapy in the traditional healthcare system?

In our food craving studies we got a forty percent reduction in craving related eating and in our recent studies with our anxiety app we found a fifty seven percent reduction in anxiety in physicians and a sixty three percent reduction in anxiety in people with generalised anxiety disorder. We are getting replicated, validated results. But the healthcare system is very slow to change. On average, it takes 17 years for any innovation to make it into the healthcare system. I think the system is going to get disrupted by the health insurers. They are always looking for cost savings and they know they are missing something with traditional medicine. If digital therapeutics can show cost savings over traditional methods then I think we are going to see greater, widespread adoption.

To finish, how has studying the science underpinning mindfulness impacted your meditation practice?

It has helped me articulate what I learn experientially. It has helped provide a conceptual framework that has refined and clarified my experience. Concepts and wisdom feed into each other. Concepts are done in the service of wisdom but our thinking brain does not hold a candle to our feeling body. If I understand a concept, I can look to see how it plays out in life and I can test it as a hypothesis. It gives me a framework to see how the practice is working and allows me to measure results. Mapping out these concepts allows me to apply them and use them in the service of wisdom.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.