Researchers from the University of Gloucestershire have recently carried out a study examining whether a walk with lemurs through a naturalistic enclosure can reduce both psychological and physiological stress. Dr Rachel Sumner and Prof Anne Goodenough followed 86 participants as they took a walk on the wild side in the UK’s largest walk-through lemur enclosure, which is part of a European protected species programme. They found that participants not only reported an improved mood after their lemur walk, but their levels of salivary cortisol decreased too. Their findings have been published in the British Ecological Society’s new open access interdisciplinary journal, People & Nature.

Our understanding of how green space can impact human health and wellbeing has been expanding in recent decades, but research tends to view nature as space or place, rather than as living things. Research that has previously been carried out with animals has tended to focus on pets or service animals, rather than wild animals. The research team, a psychobiologist and an applied ecologist, put their heads together to see if experiencing a naturalistic encounter with non-companion animals could be beneficial for humans.

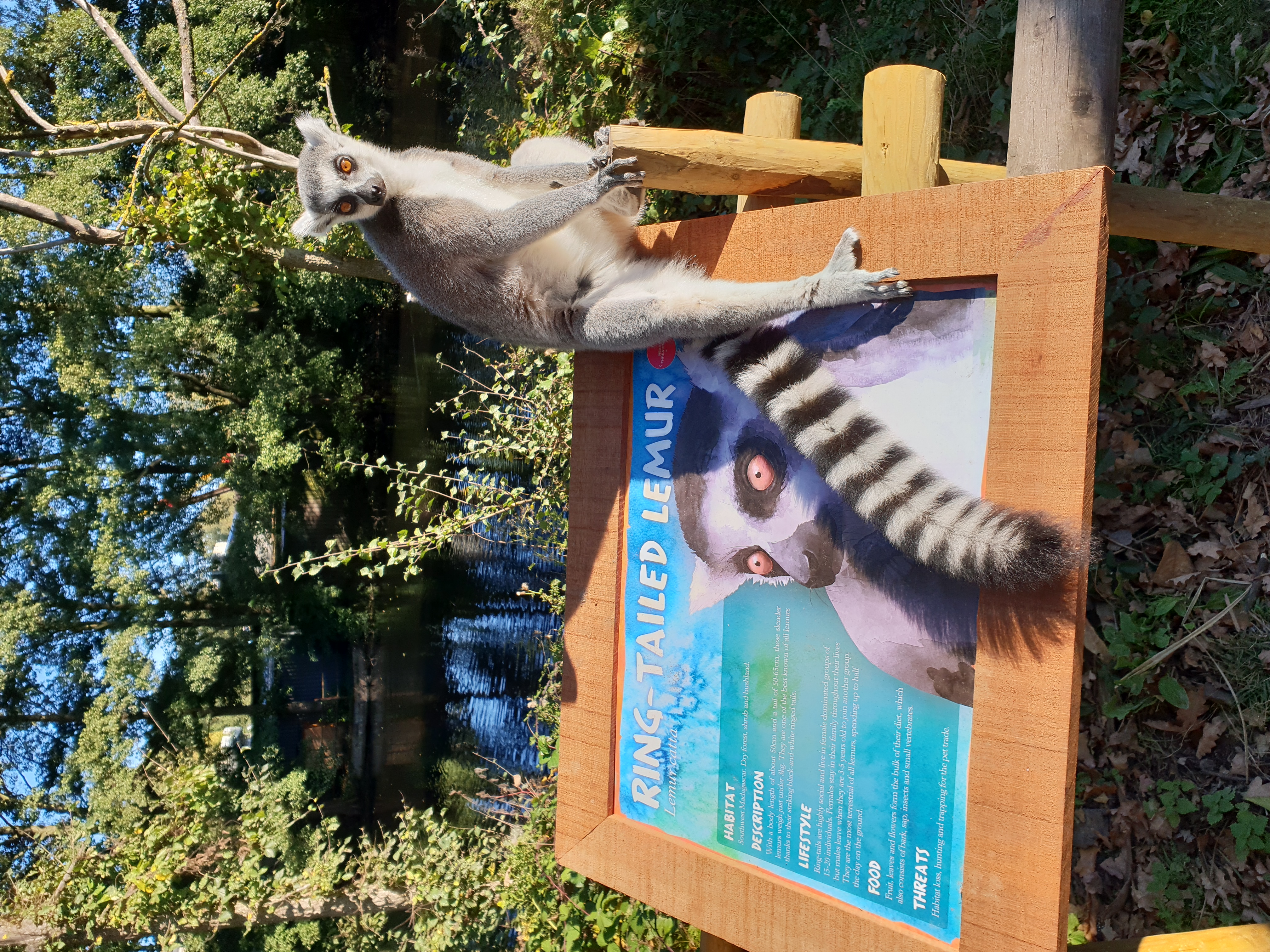

Participants were guided around the walkthrough enclosure at a gentle pace for around 11 minutes, being provided with the opportunity to stop and observe the animals if they were present. We gathered information about the participants’ specific perspectives on nature (Nisbet’s Nature Relatedness Scale), and their appraisals of the proximity and number of the lemurs, in order to understand whether these factors may influence the degree of stress reduction observed in participants. These aspects were included to add more depth to our understanding of how and why interacting with nature (in whatever form) may provide benefit.

We found that after the brief walk, participants reported improved mood and produced less salivary cortisol. In further analyses we found that participants’ reported nature relatedness, and their appraisals of lemur number and proximity accounted for almost 40% of the variance in cortisol reduction observed when controlling for baseline levels. This is the first time that cortisol has been shown to be reduced by an animal encounter that is not in a specific domestic or therapeutic setting. In related work, this specific walkthrough enclosure and its visitor footfall has been shown to have no negative impact on the lemurs’ wellbeing. This provides support for a beneficial encounter for humans not coming at the cost of the animals’ welfare.

Whilst this study was in a captive animal setting, we suggest that similar, if not maybe greater, associations might be found in encounters with animals in the wild. With the rise of nature-based social prescribing being offered throughout the country, particularly in the form of nature walks, the added element of animal encounters may provide enhanced benefit for those that are very responsive to nature. The findings also suggest that wildlife parks or zoological gardens may also make good venues for social prescribing activities. It adds to the existing knowledge on biodiversity and human wellbeing, providing further weight to the importance of conserving and protecting animals as well as natural settings to provide benefit for both humans and wildlife.

Dr Rachel Sumner is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Gloucestershire.

Prof Anne Goodenough is a Professor of Applied Ecology at the University of Gloucestershire.