Patience. Perspective. Perseverance.

We’re going to need these qualities more than ever to survive the COVID-19 pandemic and successfully rebuild our economy and our lives when this crisis is over. If these strengths were driving our response to this virus, the world would be in a lot less trouble—and we wouldn’t see people flocking to beaches and beauty parlors at the risk of contributing to a new surge of COVID-19 infections.

We all need to take a lesson from the “The Greatest Generation”—a remarkably resilient population born and raised during the Great Depression and challenged to endure more hardship and sacrifice as they came of age during World War II.

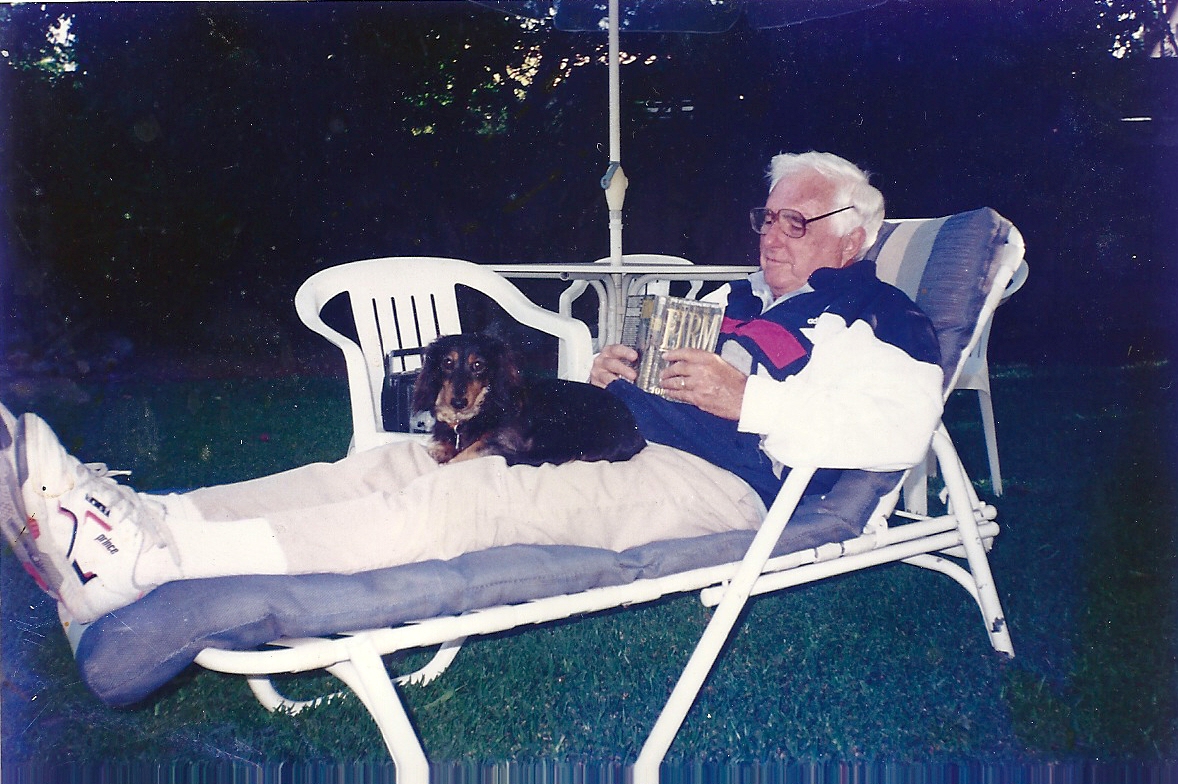

I had the good fortune to be married many years to a man of this generation who helped me through the rough spots in life by saying, “This too shall pass.” Joseph N. Bell was 34 years older than me. He died peacefully at home in 2013 at 92. As a boy growing up in Indiana during the Depression, he saw his family go from affluence to poverty overnight. And as a young man, he eagerly enlisted in the U.S. Navy just after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Waiting patiently in the midst of uncertainty was one of the life skills he was grateful to acquire during World War II; he flew transport planes around the South Pacific, and played a lot of bridge and poker games between missions.

It’s not hard to imagine how he would respond to this pandemic.

During his years as a columnist for The Daily Pilot in Newport Beach, CA, Joe once wrote: “The Depression taught most of us that there is a commonality in despair. And when it touches virtually a whole society, we learn to work together with compassion and respect. Life was reduced to simple verities that carried over to family relations and trust between people. And that, in turn, carried over to an unparalleled national effort in World War II, both at home and in the military.”

He often talked about how he was shaped by these events. He understood the power of a nation in which individuals are willing to set aside their personal agendas to do what is necessary for the common good. He kept fear at bay by focusing on the fact that the odds of survival were nearly always in his favor. He knew how to wait for things to get better. And they always did, because he was able to live in the moment and enjoy small pleasures—even in tragic times.

If he were here today, Joe would shelter at home with the sports section or a book and a martini, perfectly content to listen to a Beethoven symphony or watch a Fred Astaire movie rather than obsessing over every depressing turn of events on the nightly news. And he would encourage parents to bring more play into their children’s days, rather than trying to replicate their over-scheduled, pre-pandemic lives.

Joe was good at doing nothing.

He once wrote a column about “creative indolence,” which he defined as “part dreaming, part ability to suspend oneself in a kind of ethereal space where there is no direct contact with the world around us and no sense of time.”

I find it very difficult to disengage from the pandemic. Every day brings another revelation about how COVID-19 can kill or how our national response to it is falling short in dangerous ways. Following it all, play by play, is making me a little crazy. I don’t sleep well, dream about toilet paper, and never know what day it is. And I hardly ever find something to laugh about.

What I need is Joe’s patience, perspective and perseverance. And I need to lean into indolence instead of fighting it.

Joe would want me to do my part to “flatten the curve” by staying home, and to find ways to help others. But he would also want me to step back from the scary world out there and lose myself in a book, or a symphony or a daydream.

I just need to remember that Joe was always right when he reassured me, “This too shall pass.”