We were told it was an “old person’s disease.”

When COVID-19 first attacked the United States this spring, it was certainly true that our oldest citizens bore the disproportional brunt of the cases and subsequent deaths. And so we told them to shelter, and stay out of our way, mostly “for their own good.”

But this initial labeling of COVID-19 as an old person’s disease clearly led young people, particularly younger white people, toward complacency. After initially flattening the curve in many regions, we acted like we were out of the woods as long as the older people still stayed home. Young people returned to gyms, bars, and salons, armed with a sense of invincibility and the blessing of local leaders, and the inevitable rise in cases came.

I don’t begrudge the desire to return to normalcy. But as a result, the median age of COVID-19 cases is falling every day, and we’re finding that maybe it wasn’t just an “old person’s disease” after all.

This me-first approach to public policy is made possible when we are divided by race, gender, socioeconomic status, or in this case, age. The generational divide created a scenario where one group of people—the young—could fill the bars on Taco Tuesday, once we crammed another group—our seniors—back into their apartments, houses, and nursing homes.

This is what happens when younger people don’t have connections to older people, particularly older people outside their families. They’re less likely to see themselves as part of a greater whole, as part of a social fabric. They are their own independent entity.

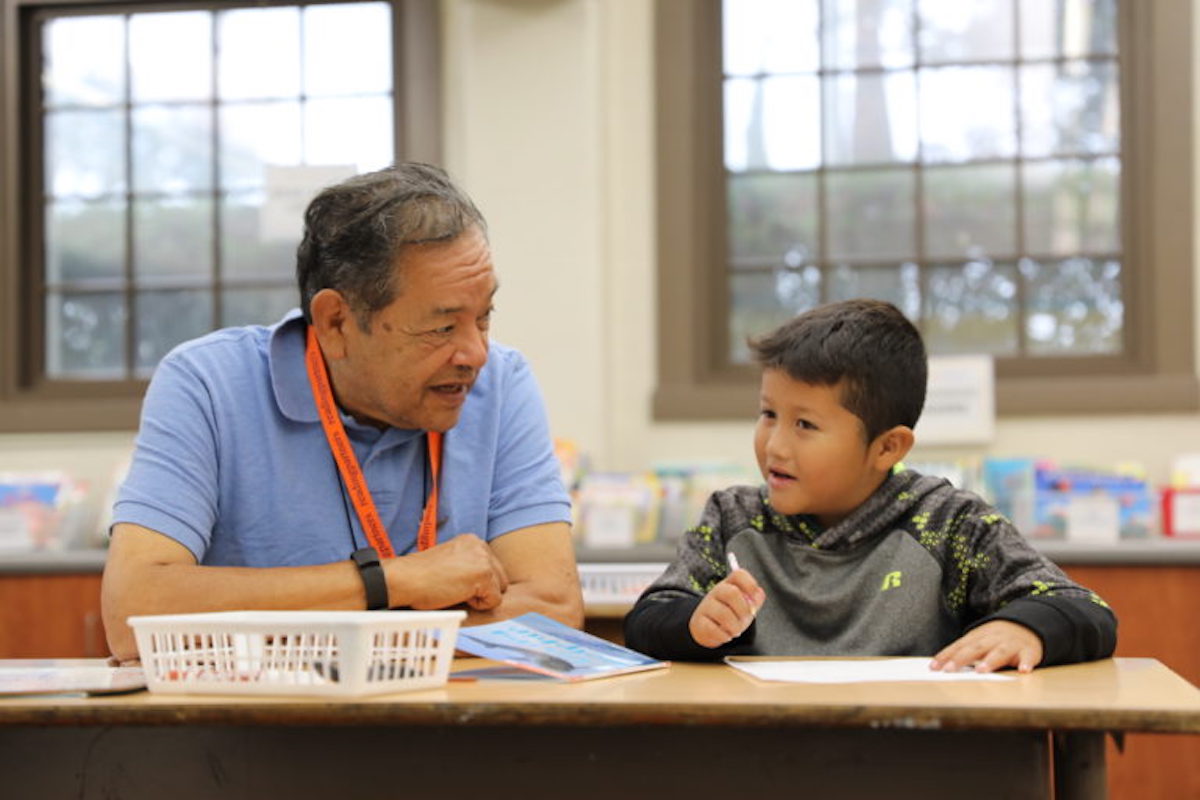

We know that increased interaction builds empathy for all involved. We are seeing it with the Black Lives Matter movement now. We saw it a year ago with #MeToo. If you see older people, and know older people, and value older people, you will develop a shared vision with them, and work to do what is best not just for you, but for them, and as a result, for our society as a whole.

There are certainly bright spots that show what’s possible when we want to create shared visions, even in our currently remote world. In New York, DOROT created a weekly intergenerational conversation club on Zoom to temporarily replace their in-person intergenerational activities. In Los Angeles, the Motion Picture and Television Fund, L.A. Works, and others rapidly scaled up a new friendly calling program to reach out to isolated older adults. These organizations know how vital these connections are between old and young, and despite vast challenges, are not letting them fall by the wayside.

At The Eisner Foundation, this is why we support intergenerational programs – to foster those connections. Because we know that when we identify with each other and learn from each other, we will do what is necessary to care for each other. Even if it’s hard. Even if it means no tacos for a while.

These programs are actively repairing a frayed social fabric, combatting the decades of age segregation. We need empathy for others more than ever as many areas of the country are moving to shutter public spaces once more. So as we retreat to our homes again, I hope we can take this time to reflect on what is truly best for all of us, not just some of us. It’s time to connect with younger or older members of your family and friends. Participate in one of the many intergenerational efforts that persist despite social distancing. And make the personal choice to do what is best for everyone’s long-term health, not just your short-term happiness.

And then take the long view – healthier and happier people of all ages make for stronger, more resilient communities that will be able to bounce back when this is all over.